“There were six to car, that’s including the driver. But you know, the driver himself could’ve been overpowered. But they trusted us that much that they stopped to feed us lunch. We could have run away but they trusted us that much. ”

— Kazuki Hirose

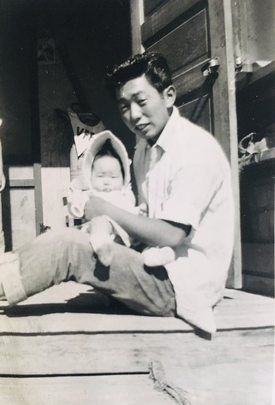

A first time conversation with Kazuki Hirose has all the familiarity and warmth of talking to an old friend. His fond reflections of growing up in Silicon Valley’s beautiful farm country and the friends he would meet in camp—many of whom are now gone—permeate the stories he tells, revealing the blessing and curse of living well into your older years.

Yet today, he is surrounded constantly by a loving family and supportive children, who came to watch his remarkable story get recorded at the Japanese American Museum of San Jose. Kazuki and his older brother Kazuto were two of the nearly 300 young men who organized to resist the draft and so-called “Loyalty Questionnaire” while imprisoned in Heart Mountain. These draft resisters, (formally known as the Heart Mountain Fair Play Committee led by Frank Emi), highlighted the government’s hypocrisy in wanting imprisoned Japanese Americans to willingly go fight in Europe. The name “fair play” represented what they considered an exchange of mutual respect. They would agree to the draft only when, and if, the government released the Japanese Americans from their isolated prisons. Of course, history would tell us otherwise: 63 of the men were tried in the largest mass trial in Wyoming’s history before an unsympathetic judge who sentenced them to serve time in federal penitentiaries.

But when asked if he felt any kind of sadness, even bitterness, about what happened during the war, Kazuki’s innate personality has embraced a sense of acceptance. “I didn’t feel nothing. I didn’t care. My friends, too. They said the hell with it, let it go.”

* * * * *

So Pearl Harbor happened right around your birthday. Do you remember the day that it happened?

I was about 14 or 15, somewhere around there. I still remember the day, you know how you were treated. One day, just like that. They outballed you, meaning they don’t talk to you, or play with you like we were playing baseball or anything. And one of my friends said that the thing that hurt him most - he was from another school - he said everybody was friendly but on that day, even the teacher called him a ‘Jap boy.’ And he was really tee’d off on that. To be called a Jap boy, that day of the war. He said ‘I didn’t do nothing.’ And he just let it go. But at that time, even the school didn’t care. We were ‘Japs.’

Were you living in a predominately Japanese community?

No, there weren’t that many Japanese around. If you accumulate them from Japantown to inaka [countryside]. Basically it’s a small town, or it was. God it was beautiful, before all these cars came in.

It was all country.

It was very much country. Even the rural routes, there were very few roads.

So you found there was some backlash when you went to school?

Where my dad was working, they were from Switzerland. But they were very good, they weren’t hostile. They were just ordinary people. They were very good people.

Kind. So do you remember anything that your parents said to you and your siblings when Pearl Harbor happened? Or do you remember anything about their reaction to it?

No. We were way out, like today it feels like a jungle. So nobody bothered us. Close by our coach lived there, you know, our high school coach. And of course we played for him. He was a really nice guy. He was Swiss too. Mostly the hakujin, they lived, like the Japanese too: Kumamoto, from Kumamoto, Fukuoka, from Fukuoka, you know. So, they kind of held together. On their side. I mean my folks, they held on their side mostly from Kumamoto.

Right, so many people came from Kyushu too and were here. And so, were your parents shocked that Japan had bombed Pearl Harbor?

No, I think my mother and my father unknowingly, they used to talk together, you know like bedtime, or whatever. And they kind of had a hunch, I think, how Japan was gonna come. Not to Pearl Harbor but they knew somewhere close by, the war was coming.

They had a feeling?

Yeah, they had a feeling.

Wow, ok.

Because I remember, around our area there was a lot of Kumamoto. Not a lot, but you know, what there were. My father used to be quite a drinker. So all his Kumamoto buddies used to come over. And I kind of picked it up because we were going to Japanese school. And I could understand what they were saying, so I kind of picked it up too from them that war was coming. It wasn’t close, but it was when? They kind of knew. And my grandfather, he was a small fella, I remember he was a small fella, but very, very smart. So he made a lot of money here and he took off to Japan.

Oh, before the war started?

Before the war started. How long ago was that? Under a year anyway. And I think on his back shoulder he knew, too. We didn’t want to have to go back but he wanted to take my sister back, you know. But he knew that my mother was [against it].

And I was supposed to go Colorado. You know when time came, when they kind of had a hunch, [they thought] I go be adopted with this family of her’s. It’s kind of relation, far. But my mother said, “No. I don’t care how many we have, you’re not going to break up the family.”

She wanted to keep everyone -

Yep, all together.

So when the executive order came out, 9066, and you had to leave San Jose, where did you go? What assembly center did you go to?

We had to be pushed into Santa Anita. You know where the horse runs?

Were you in the stables or were you in the barracks?

Well we were in the barrack, but some uncomfortable ones [were in the stables]. You know, they didn’t like it. They ended up in the stables. I used to tell them, my friend, “Oh, you guys smell!” You know, rub it in.

Yeah, it was awful.

We were in a pretty good place. We had a lot of fun there. You know, there was a real popular guy. He was one of the top bowler at the time. A guy named Fuzzy Shimada. And he is a sleeper. He used to sleep all the time, a lot of the time. And he was sleeping with a bunch of boys, you know, athletes? And they pushed him right into the worst place, right out where everybody was walking back and forth! [laughs]

But he was asleep?

Yeah he was asleep. He was a good sleeper! And I don’t know what happened after, you know, he woke up. I just knew the guy and I knew the guy that pushed him out, too.

That is really funny. Now when you left San Jose, did your parents have anyone to watch their things? Did they just lose the house?

At the train depot, a few hakujin were there. But they were saying “bye” to other people. And of course everyone was busy though, they had their children to watch and make sure they’re there, make sure they had their little hats and they don’t wander off. And you know, we weren’t treated the best, apparently, you know. And there was soldiers there, huh. And after three months we got pulled out and had to go to Heart Mountain.

So do you remember that trip? That trip from Santa Anita to Heart Mountain? Because I mean that was long.

Yeah, that was a wicked one! Oh Jesus! You know, it wasn’t, I’ll tell you, it wasn’t the streamliner one. It was an old; rattles and everything. And you could hear the kids crying and, you know kawaisou, huh? [Poor things]. And they made a couple of stops. And you know, my father and his group, the first thing they think about more faster than milk, is booze. They tried to get or buy beer or whatever it was. But they wouldn’t sell it to them.

Wow.

And while traveling, the train? Bad as it was they had a curtain, lo and behold, and they never had that open. I guess safety wise, or, something.

Right. Did you ever peek out the curtain?

Oh yeah, everybody peeked out. I didn’t want to see the outside. But I saw a real lighted place, and I was telling my friend, “That must have been Reno.” You know, when we passed it. I saw a lot of lights and I didn’t even bother to look out. We never bothered to look out. There was a few of our groupy friends were sitting there and says, “Oh we don’t care.” We didn’t, I didn’t know anything about Reno then.

During a short break, Kazuki’s daughter explains what happened to the family’s property when they left for camp. The Hiroses entrusted their things with people they knew but nearly everything was stolen from the barn where the property was stored, which was a long distance from the main house.

Let’s talk about Heart Mountain. What was your first impression of Heart Mountain?

When we got off of the train? Lo and behold there was dust flying all over the place and I thought, “God look at me here. An angel like me getting thrown in” [laughs]. No, no. But it was dusty and there were little kids walking by their parent and grandparents, crying like heck. And the grandparents got a handful by themselves. So we went right with them. And we were told what to do because they all had rifles, you can’t buck a rifle. I think they would’ve done something if there were no bullet because they were just young soldiers, yet. My brother and I were thinking after a while, ‘How come we treat those soldiers bad? Look at their faces, they’re young.’ They don’t know either what the heck’s going on. Still that didn’t stop us, they were still hakujin you know [laughs].

You were still on this side of the fence with the rifles pointing inside.

Oh yeah, and the towers were already there. They had their facilities and what they want up there with guns and down below they’re walking. I don’t think they meant really no harm. They didn’t really know how we would act. So you couldn’t blame them, huh?

When you went into Heart Mountain you were about 14 or 15?

Yeah maybe a little older.

16 or so? So you were still in high school. Did you start school?

Yeah. You didn’t start for a while, but I went for so many months, I guess.

Before the loyalty questionnaire came out, were you having a good time? Were you meeting new friends?

Oh yeah, met a lot of friends. Some kind of rough - you eye each other, not liking each other because you know, they’re from L.A. And you don’t know what to expect and they didn’t know what to expect. So we looked at each other in a rotten way. Sometimes we fought. [laughs]

And were your parents working in camp?

Yeah. My mother couldn’t work, because she had a whole handful herself. But my father worked at, believe it or not, mess hall, that was the first time I saw my father with apron on, and a hat. First time I looked at my brother and laughed said, ‘Papa’s in the [inaudible].’

Yeah that was a job a lot of parents did. They were cooking in the mess hall.

That was a farce, huh?

The food must have been pretty mediocre.

As far as I know and my father knows, we had a lot of egg foo young. And people used to monku [complain]. My father would come home and say, ‘I don’t know why they’re complaining,’ he said. ‘At home before they probably didn’t have anything better than that.’ Maybe that was true. I know we didn’t. You know, my mother had to plant her own vegetables. That’s one thing she did, she planted vegetables as big as this room. And she took care of that, took care of all of us, took care of the house.

My mother had that kind of personality where all the other ladies used to come see her. She was busy but she welcomed them. They always got together. You know when Japanese people, menfolk, they gather, even obasans, they would play hana [card game] and things. My folks never knew how expect my father. My mother would say, ‘Don’t belittle your father because that’s how we used to eat.’ He played pool and hana, he was good at it. Maybe he had to be good, not ‘was’ good, he had to be, to feed 13 of us. But I enjoyed every bit of it, growing up with that many. My father used to love sports, he used to kick the ball, throw the ball, it depends on the season on the ranch. So we got pretty good at sports.

You had a warm family, it sounds like.

We were very, very poor, but we didn’t know it. We thought we were wealthy. But other people I guess, I don’t know how they felt but that’s how we felt. We thought we had a lot, maybe not the best meat or things but now when you think about it, we were lucky. Meat’s not good for you.

Right you were eating your own vegetables.

Right, uh huh.

*This article was originally published on Tessaku on April 2, 2019.

© 2019 Emiko Tsuchida