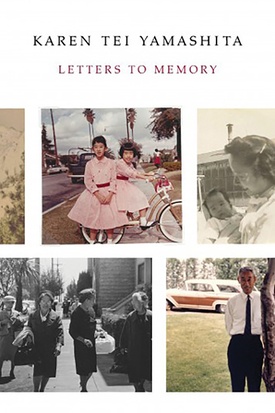

With the end of the Nisei generation upon us, their children, the Sansei, are sometimes fortunate enough to inherit a record of the life of their parents and grandparents. That is, if the record – photos, letters, artifacts – was ever kept or still exists. Sansei Karen Tei Yamashita is one of the lucky ones, for she inherited a trove.

The Los Angeles-based novelist and playwright pulled her family’s past together in her latest book, Letters to Memory (2017, Coffee House Press). Instead of just chronologically stringing along what she found, however, Yamashita frames the findings in a series of musings when missing pieces present themselves – as any family history is wont to have. “Retrieving the irretrievable,” she calls it.

But Yamashita writes her ruminations as letters to Homer – as in the Iliad – and other historical and spiritual muses, so be ready for repeated clicks to Wikipedia. In the parlance of us ‘60s- and ‘70s-cultured Sansei, she sure is “trippy.”

As is common in the Japanese American canon, Yamashita’s father, John, and his six siblings live the average pre-World War II American life. In their case, it’s centered around the Oakland West Tenth Methodist Church in Oakland, CA.

Then their lives are irrevocably inverted by the forced removal of Japanese Americans from the West Coast and their incarceration during the duration of the war – the “justified injustice,” as Yamashita labels it. Along with most of Japanese descent around the San Francisco Bay Area, the family is removed to the Tanforan horse racetrack facility, then to the camp called Topaz in Utah.

John Yamashita is able to leave Topaz by enrolling in a seminary at Evanston, Ill. His siblings also leave the camp via jobs or by attending colleges in the Midwest and East Coast. And, fortunately for members of future Yamashita family generations – including Karen Tei – the Nisei brothers and sisters are prolific letter writers.

As his daughter shows throughout Letters to Memory, John Yamashita remains upbeat despite his wartime experience. He returns to Oakland and the Methodist Church there near the end of the war as Japanese Americans begin leaving the camps and, as Karen Tei writes, “turned the church into a hostel to receive the residue of returning folks, many now homeless…”

In a letter to his younger sister Kay during that time: “… I say all is adventure and more adventure and if you don’t want it – then don’t venture forth in faith, but be content with things as they are … Here’s to you for new worlds to be.”

Becoming a Methodist minister who would later relocate to and serve in Los Angeles, John Yamashita writes in a letter that “…my life and vocation is no picnic or bed of roses…” Daughter Karen Tei describes 1945 through 1947 as “years of intense physical and emotional work, the practical labor of rebuilding a postwar community, but it was also a period of intense personal, political, and philosophical questioning.”

However, she later concludes, “…[T]he empathy upon which the community depended, as if their daily bread, was based in an expression of what he called love and creative laughter,” and that laughter is “just necessary, a survival tool, but also a way of perceiving.”

“John always expressed a dislike for the guy with a chip on his shoulder. He thought if you couldn’t get rid of that injurious chip, that it would find its way into your heart and corrupt your being. You could never be a whole person carrying about a wounded sense of being wronged. Your anger would surface and hurt others, usually those you loved best. He thought camp was the most unjust, cruel and oppressive event of his life, but he was adamant that it would not control his character, well, he would say, his soul.”

It might be easy to knock Karen Tei Yamashita’s cerebral explorations and sometimes “huh?” passages – as like losing a satellite’s signal after it ventures too far into space. However, she is working on an elevated intellectual plane which produced a unique take on Japanese American history. And, this passage by the self-described “PK” – the preacher’s kid – needs no speculation as to its meaning:

“…[T]hey knew what was happening to them was significant and wrong, that justice might not happen in their lifetimes. What they saved shows that this is true, but we children thought that they were nostalgic packrats. Now we are old and nostalgic ourselves and comb through this business like we invented it. … amateur historians, trying to compensate for the fact that as kids we were too distracted by the idea of this past to be actually immersed in it. Shame on us. Now they are all dead, and we didn’t save their brains, either.”

*This article was originally pubished by International Examiner on May 8, 2019.

© 2019 Ken Mochizuki