In November 2018, the New York Times wrote an article highlighting the work of Father Ruskin Piedra, the priest of the church Our Lady of Perpetual Help in New York City.1 At 84, he busies himself with supporting litigation on behalf of immigrants - some from his own parish - to protect them from deportation. Amid the dreadful news of family separation and confinement of children in detention centers, Father Piedra’s work is a hopeful reminder that despite the callousness of the current administration’s policies in regard to immigrants and human rights, there are those working to help them and address their troubles.

The story of Father Piedra recalls other supportive efforts by Catholics during the World War II era. As shown in a previous article in Discover Nikkei, Dorothy Day defended the rights of Japanese Americans by publishing realistic accounts of the anguish of those behind barbed wire. Meanwhile, throughout those same years a number of Catholic priests took up responsibility for assisting the Nikkei community during their removal, confinement and release from camp.

One such figure worth celebrating is Brother Theophane Walsh. Born Edward George Walsh in February, 1904 to Irish American parents, he grew up in Boston. A dedicated student, he took night classes to pursue his education even while working days as a salesman and clerk. In 1921 the young Edward began a vocation with the Maryknolls, a Catholic missionary order founded in the 1910s, whose members evangelized in Asia and elsewhere. He was influenced by his brother Willie, who had previously taken a Maryknoll vocation and had entered the Venard seminary in Pennsylvania. The young Walsh took the name Theophane after Saint Jean-Théophane Venard, a French Catholic missionary and martyr in Indochina.

After leaving the seminary, he was sent to Los Angeles to work in the Little Tokyo Parish, where he was fully ordained in 1930. During his time in Los Angeles with the Maryknoll’s Japanese Mission, Walsh was limited in his activities by repeated health problems, which required extensive medical treatment and hospitalization.

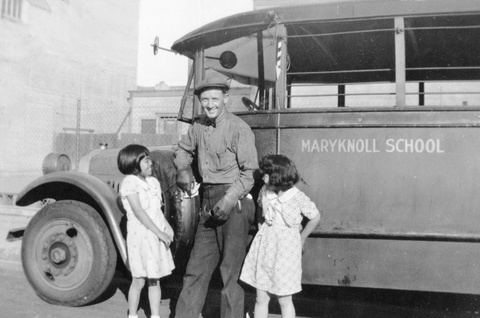

Still, he worked with Japanese-American youth in various ways. He was solely responsible for putting together the bazaar run by the Japanese Mission and took the lead in organizing the school buses that transported students to and from the Japanese school. He was most notable for working with Boy Scouts, in connection with the Ad Altare Dei movement of the Scouts. In 1926, Walsh helped organize one of the oldest Japanese-American troops in the U.S.

In 1942, in the wake of Executive Order 9066 and the forced confinement of West Coast Japanese Americans, Brother Walsh committed himself to helping the Nikkei community Brother Walsh committed the himself to helping the Nikkei community in any way possible. Together with Masamori Kojima and Setsuko Matsunaga (later Nishi), he organized a speakers bureau to make the case for the loyalty of Japanese Americans. In conjunction with Fathers Leopold Tibesar and Hugh Lavery, he proposed to move with his Nikkei parishioners to a settlement outside the West Coast, and he furnished to the Tolan Committee - the congressional group studying mass removal - a list of names of potential resettlers. In a 1971 issue of Rafu Shimpo, Brother Walsh was remembered in particular for helping organize temporary shelter for Nikkei families from Terminal Island, following their forced eviction by the Navy in February 1942.2

In Fall 1942, Brother Walsh went off with other Maryknoll missionaries to the Manzanar camp, where he helped families adjust to camp life. A year later in 1943, Walsh left for Chicago. Under the direction of Bishop Bernard Sheil, he helped establish the Catholic Youth Organization’s Nisei Center, a center that assisted young Nisei resettling outside of camp. The center’s development came at a time when family groups were beginning to resettle in large numbers, with Chicago being the principal destination. In August 1944, Larry Tajiri reported in the Pacific Citizen that racist hostility against Japanese Americans was rising due to lies by the Hearst newspapers, who charged that Nisei resettlers were arriving in Chicago without “any investigation by the FBI… and by simply changing their tune and signing papers to be good.”3 By his supportive work, Brother Walsh provided encouragement to local Nisei.

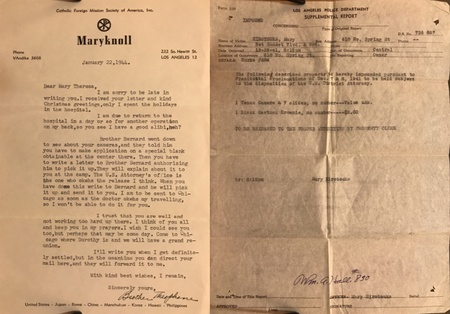

Even as he worked in Manzanar and Chicago, Brother Walsh maintained correspondence with Nisei friends dispersed in other camps. In particular, he corresponded with a number of his parishioners from Los Angeles who were sent to Heart Mountain. In one letter to Mary Theresa Oishi (née Hiratsuka), Walsh sent instructions on how to retrieve family cameras confiscated by the LAPD following Pearl Harbor, along with the copy of the police report.4 Such a letter not only sheds light on the benevolent acts of individuals like Brother Walsh, but reminds us to what extent the state dominated the lives of Nikkei in time of war, with local policemen later participating in the roundup with soldiers.

After the end of the war, Walsh remained in Chicago. His continuing work with the Nisei Center, including English instruction and scoutmastering, were applauded in the Chicago newspapers on several occasions. During the U.S. occupation of Japan, he briefly served as a missionary in Japan for the Maryknoll group, delivering lectures on forging bonds between the U.S. and Japan.

In one 1948 lecture cited by the Nichi Bei Times, he spoke at the Tokyo Industrial Club about “the future of the Japanese in America” and the potentially favorable future for the Nikkei in the United States.5

Following the conclusion of his mission, he returned, first to Chicago and later to Los Angeles. He labored constantly to work with Nikkei youth and gain community support of public institutions. In his article for the Kashu Mainichi during the 1950s, he extolled Nikkei youth for forming clubs and called for “more adult active participation in the work of any organization of their choice.”6 He ultimately would be named the International Boy Scout Commissioner for interracial groups. In 1956 he was awarded the medal of Saint George for his Scout work over thirty years.

He suffered again from poor health in later years, and died at the Maryknoll Center in Ossining in 1981.

Brother Walsh’s wartime efforts in Los Angeles and Chicago offer a lesson in humanity and a chance for reflection by Americans. Today, when racist rhetoric - especially from the right – has grown increasingly visible and normalized in political discourse, his devotion to interracial justice serves as a beacon. While not everyone can devote their lives to activism like Brother Walsh or Father Piedra, their lives suggest some of countless ways to advocate for those victimized by prejudice and to heal divisions within American society.

Notes:

1. "The Very Busy Life of an Immigrants' Rights Priest in 2018," The New York Times, November 8, 2018.

2. “Brother Theophane Toasted Tomorrow, ”Rafu Shimpo, August 25, 1971.

3. Larry Tajiri, “The Hearst Hand in Chicago,” Pacific Citizen, August 12, 1944.

4. Letter from Brother Theophane Walsh to Mary Theresa Oishi, August 1944. From the Author’s collection.

5. The Nichi Bei Times, October 31, 1948.

6. Brother Theophane Walsh, “A Few Words of Praise…” Kashu Mainichi, February 21, 1959.

© 2019 Greg Robinson, Jonathan van Harmelen