Julio Mizzumi Guerrero Kojima is a folk musician and preschool teacher of Nikkei origin, who was born in a small village in Veracruz on the shores of the Papaloapan River, also known as “river of the butterflies,” in 1970. The village of Otatitlán (which means “place of the bamboo” in the Náhuatl language) where Julio grew up is part of an incredibly rich microcosm in the region called Sotavento (“place of high winds”). The many different cultures flourishing here have intersected in this region of Veracruz for thousands of years.

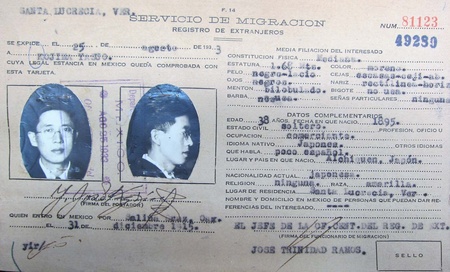

Adding to an already diverse range of cultures, Veracruz received a wave of Japanese immigrants more than 110 years ago. During the first decades of the 20th century, Japanese immigrants dispersed throughout several regions: In the south, to the port of Coatzacoalcos and Minatitlán; and in the central part of the state, to the port of Veracruz as well as Orizaba and Córdoba. The first large group of close to 1,000 workers arrived in 1906 to work at La Oaxaqueña, a hacienda in southern Veracruz. A Japanese company, Tairiku Imin Gaisha, recruited the workers in Japan and brought them to Mexico to provide labor to the U.S.-owned sugar hacienda, with an area of more than 10,000 hectares (more than 24700 acres).

Due to the terrible working and health conditions at La Oaxaqueña, several Japanese workers died of malaria and gastrointestinal disease and were buried there. The majority of the workers, fed up with the conditions, left the hacienda and walked or hopped freight trains to northern Mexico, in search of better jobs and the possibility of entering the United States.

Years later, a small group of Japanese immigrants came to Otatitlán. Perhaps the first to settle in the village was Bunji Iide, who had probably been recruited to work at La Oaxaqueña, since he had arrived in Mexico in 1906. Ten years later, doctors Kendo Koi and Junsaku Mizusawa1 settled in Otatitlán, where they cared for thousands of patients and became so beloved and renowned that when they were forced to move to Mexico City after war broke out between the United States and Japan in 1941, municipal authorities and local residents petitioned the President of the Republic, Manuel Ávila Camacho, for their return. The other immigrant who arrived to the village in 1915 was Julio’s grandfather Yasuo Kojima, who was from Aichi Prefecture.

Kojima quickly adapted to the Otatitlán community, taking the Spanish name José and settling down with an indigenous woman, Genoveva Salas. Their son, José Ernesto Kojima Salas, was born in 1923, but the strong winds that blow through people's lives transformed this from a love story to one of betrayal, as Julio tells it. Yasuo Kojima abandoned Genoveva and his newborn son and ran off with one of her cousins, with whom he formed another family. Little José Ernesto grew up without a father, but also without any sense of the family roots that bound him to the history and culture of Japan. Decades passed before the winds of Sotavento brought new ideas, and Kojima's descendants set out to discover and reconstruct that somewhat obscure part of their background.

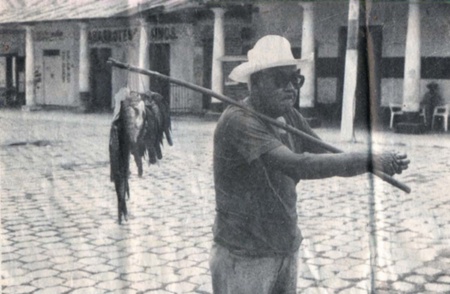

José Ernesto Kojima, like most people living along the Papaloapan River, made his living from activities related to fishing and farming. Kojima specialized in river carpentry; that is, in building small boats used for fishing and for ferrying people to other villages. José Ernesto married Sofía Villavicencio, and the couple had eight children.

Although for most of his life José Ernesto expressed no interest in looking for or having contact with his father, it was ultimately Yasuo who sent, at the age of 88, a letter to his son asking him to visit him at his home in Mexico City. The meeting never took place, but in a certain way it built a bridge that intrigued the entire family as to the origin of their name.

José Ernesto’s eldest daughter, Margarita, was among those most interested in learning about the Japanese origin of her family and openly acknowledging it. Although her grandfather had abandoned her father, Margarita recognized that although those roots are invisible, they are part of her family's legacy and could not be erased. Margarita then decided it would be a good idea to show the positive ways in which so many Japanese immigrants had contributed to the village of Otatitlán, with their work, honesty and service to the community. The simplest way that Margarita acknowledged that legacy was to give four of her six children Japanese names.

Aware of that situation, Julio Mizzumi and his five siblings, led by his mother Margarita, resolved to honor their roots and their family identity. This was a difficult task, since the community of Otatitlán and the wider region it is part of have multiple cultural origins going back to the founding of the nation of Mexico before the Spaniards arrived. Various indigenous peoples lived in the Sotavento Region at the time of the Spanish conquest in 1521; these peoples paid tributes to the Mexican empire, supplying it with cacao, amber and guacamaya feathers, among many other items. During the colonial period, with the arrival of European and African people, the region became home to diverse traditions and customs resulting from both the nature of the place and the influence of Amerindian, European and African cultures.

It was in this vast mosaic of cultural influences that Julio Mizzumi and all of his family began to take steps to promote their cultural roots. They already had an important advantage: recognition from the community of Otatitlán for the hard work and tenacity of the Kojima family as fishermen and women and experts in Veracruzan culinary culture. Thus the family sought to conserve and disseminate, from the community itself, the popular traditions that also include son jarocho and the fandango, with an emphasis on the participation of youth and children. As a result of this first activity, Julio Mizzumi was not only recognized as a conveyor of that musical tradition but it also resulted in ties to his Japanese origin, as he was invited to give concerts and promote son jarocho in Japan in 2005.

In addition, the family began organizing another activity in the backyard of Margarita's house. That’s where they created a space known as the “Kojima Garden,” with the goal of conserving and preserving ornamental and edible plants from the region's rich ecosystem.2 They also hold son jarocho and tap dancing classes, among other activities, through which they hope to spread, with the community's participation, values based on conservation and cleaning of the environment and the ties of human solidarity, respect and coexistence.

Notes:

1. You can read their story in “Kendo Koi and Junsaku Mizusawa: Japanese Doctors in Veracruz and Oaxaca” (Discover Nikkei, Nov. 2, 2018)

2. Detailed information about this can be found in Verónica Espinosa G. “The Kojima Garden of Otatitlán, Veracruz”, not yet published.

© 2019 Sergio Hernández Galindo