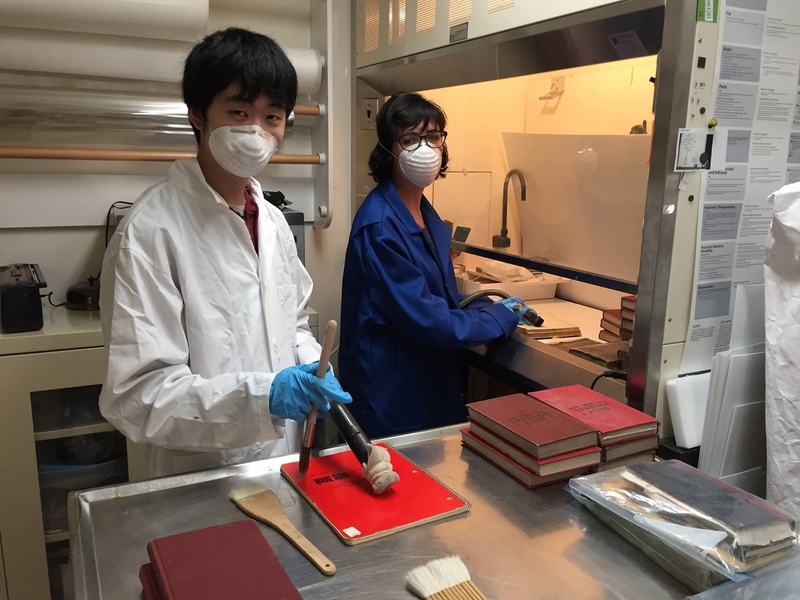

I spent the summer of 2017 in the Fuji Room at the Nikkei National Museum & Cultural Centre (NNMCC), along with fellow interns Nathan Yeo and Joe Liao. The three of us spent hours sorting through archival donations, housing them carefully and entering their descriptions into the museum database. We sat at the center of an accumulation of boxes and joked that we worked in the “Fuji Room Vault,” a second, unofficial archival storage area where collections manager Lisa Uyeda, our supervisor, stacked new donations as they came in.

Lisa appeared to be caught in an unending game of Tetris. She explained that as people were becoming more familiar with the institution, and as Japanese Canadians aged, donations were becoming steady and generous. While I worked at the table, she would wheel donations—old orange crates, dozens of pillbox hats, stacks of letters, and framed family photographs—to and from the actual archival vault downstairs.

One day, Nathan and I helped to stack an elaborate, heavy contraption of wood, wool, and cast iron into the room. We had no idea what it was. It turned out to be a home brew sake set-up, preserved from the pre-war Steveston community.

Later, while Lisa was vacuuming the spider webs from this donation, I was struck by a wave of nostalgia. “The smell of rust reminds me of my grandparents’ place,” I said with a laugh. Lisa agreed, and we speculated on the correlation between growing up with your grandparents—surrounded by faded photographs, slightly moldy books, and stories—and becoming an archivist.

I had always intended to do a summer co-op as part of my Master’s degree. The opportunity at the NNMCC wove together aspects of my research, my employment with the Landscapes of Injustice project, and an interest in archival studies and museum curation. My time at the museum also allowed me to place the focus of my study (the dispossession of Japanese Canadians) into the broader context of Japanese-Canadian history and the many ways it has been told.

Getting into the archives

When I started my co-op in May, I began working with the Tonomura Family Collection. A single box held the story of an entire family and their settlement—and re-settlement—in Canada over the course of the 20thcentury. It was preserved in glimpses through certificates, agreements, guestbooks, and photographs.

Senjiro Tonomura immigrated to Canada at the turn of the 20th century,and soon he and his wife, Kuni, had a small family: two sons and two daughters, two born in Japan and two born in Canada. After owning a boarding house in Vancouver for several years, the family purchased land in Mission and began farming in 1914.

Federal orders uprooted the Tonomuras from their homes in 1942, and then deported them from Canada in 1946. After a decade of exile, the Tonomuras slowly returned to North America and rebuilt their lives in British Columbia. As I processed their records, their story became vivid: an urgent letter from Moichiro, the oldest son, when he was imprisoned in Angler after refusing to leave his property; desperate appeals for refugee status in Japan when they were deported; congenial Christmas cards to John, Senjiro’s grandson, when he returned to Vancouver after graduating high school in 1956.To fill in the gaps between documents, I referred to a biography of the family lovingly compiled by Marlene Tonomura, John’s wife, who wrote with understandable admiration for this remarkable family.

Marlene had married John later in life and, amazed by the family’s remarkable resilience, compiled the family collection. John passed away in 2015, and Marlene donated the materials to the NNMCC, believing that their story was worth remembering and sharing. Her plastic-ring-bound family history records the story as it was told to her—with wry humour and an eye to the serendipitous in life.

Understanding the stuff on the shelves

Making sense of the donation required quick learning. At least half of the Tonomura Family Collection, for instance, is in Japanese. Yoriko Gillard, an artist and translator, sat patiently with Nathan and me to provide cursory summaries of the material that we could provisionally enter into the database, until she could return later to read them more closely.

The collection also required lessons about Japanese culture. “These are shoes,” I said one day, holding what I thought were shoes and ready to enter them into the database. “No!” Yoriko said, explaining that they were more likely a decoration used in the hospitality industry, where miniature shoes were hung in an entranceway for good luck.

Like the shoes, the holdings at the NNM can have unexpected meanings. The most mundane item will have a surprising story, depending on who made it, who used it, where it started, and where it ended up. Inevitably, the objects are understood in relation to the forced uprooting, incarceration, and dispossession of Japanese Canadians in the 1940s. It is hard to avoid the disjuncture: this is an item from before, that was carried to, or that was used right after. It casts the most mundane belongings in a different light; they become remnants, testaments, and witnesses of lives that were so suddenly disrupted.

“Everyone kept their RCMP horse blanket,” Lisa explained to me, referring to the blankets that the British Columbia Security Commission distributed to Japanese Canadians when they arrived off the trains in the Interior of BC. I imagined the blankets being kept in a basement cupboard, and wondered if, for decades, they were saved less for the moment they symbolized (that first frigid winter of internment) than for their more ordinary, practical use of keeping warm. And could this reason have changed, as the years passed on?

Lives disrupted and re-assembled

Over the course of the summer at the NNMCC, however, I realized that I was also learning about re-assembly: the re-assembly of life after the war, of research projects, family histories, and new communities.

Near the end of my term in August I helped copy-edit Jack Kagetsu’s biography of his father, Eikichi Kagetsu, The Tree Trunk Can Be My Pillow. It’s a detailed profile of one of the most successful Japanese-Canadian businessmen before the war who may have lost the most money of all Japanese Canadians in the forced sale of his property by the Canadian state.

In the biography, Jack interwove his own memories with the archival records he meticulously assembled in the final decade of his life. The personal touches are arresting: glimpses of the small history of the everyday (New Years’ celebrations, fishing trips, recitals, graduations) amidst the big history of political decisions and persistent racism that derailed the Kagetsu family’s lives.

At the end of the manuscript, Jack included a complete version of the 1942 Canadian Security Commission report on his father, and reported being appalled at the Security Commission’s misrepresentation of Eikichi. Jack says that his father was so much more than what the Security Commission reported; he was a businessman, an adventurer, a careful gardener, and a loving parent. The 300-page biography stands in conversation with—and in defiance of—the state record of Eikichi Kagetsu, which, in certain ways, justified his dispossession.

Things that my thesis will not be

I’ve spent months in government archives conducting research. Those institutions could not feel more different from the NNMCC. Rather than simply preserve material, the museum archive reflects and serves its community. Lisa is endlessly in conversation with donors and volunteers. Donors chose what stories to preserve. Researchers, artists, and community builders pass through its doors, creating projects in conversation with the past, whether as a reckoning, a reflection, or interjection.

As I went back to writing my Master’s thesis, I had a clearer idea of what it would not be. It would not be a family research project like that of Marlene Tonomura or Jack Kagetsu. It would not be a creative production like the Spatial Poetics performances or Japanese Problem (two plays that ran during my summer in Vancouver.)

My thesis was different from these projects in that I was working within academia, a fraught realm that privileges certain knowledge over others, and different because I am not of Japanese Canadian descent. But it was similar to them also, in that it was an instance of someone relating to the past, inevitably in their own way. It’s a humbling thought, but also an exciting one: rather than proposing to make a final claim about a history, I am instead joining a larger conversation.

I’m grateful for the opportunity to join the museum team for the summer and learn how archives can function as a lively hub of community. I thank the staff for exemplifying the patience, hard work, continued enthusiasm for learning, and attention to detail required to make an archives come to life.

*This article was originally published in Nikkei Images, Volume 23, No. 2, in 2018.

© 2019 Kaitlin Findlay