Journalists are spectators of reality, capable of deciphering it in a simple code that sheds light on what we understand as current events.

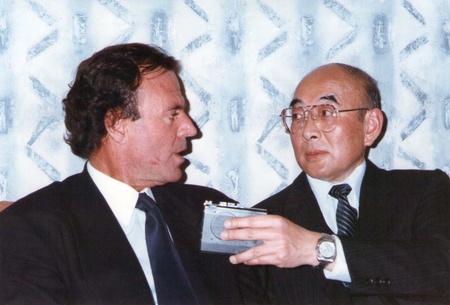

Alfredo Kato Todio is 81 years old and has a look that, from a very young age, distinguished himself from others to make a name for himself in entertainment journalism, which now in Peru seems inconsequential, as does the topic it addresses. Talking to him about journalism, his career, and the Nikkei community seems like a way to look at the past and the future at the same time.

He says that since he was a child he liked shows, movies and their stars. He was born and raised in Cañete, south of Lima. When World War II occurred, his father decided to hide in Lunahuaná. She was a native of Fukushima and in Peru she worked as a hairdresser. In 1947, when Alfredo, the oldest of five siblings, was 10 years old, they moved to Lima. “My father was one of the first to steam fish,” he says.

His restaurant in downtown Lima became known, even though it had no name, for its fan shell ceviche. Alfredo helped his father, who wanted him to dedicate himself to dentistry. “I applied to San Marcos but I didn't get it, I told my dad that I wanted to be a journalist. Since I was a child I subscribed to entertainment magazines from Argentina that I received by mail,” says this journalist who found the opportunity to dedicate himself to this profession at the Catholic University of Peru.

Following the vocation

“You're going to die of hunger,” was the father's warning before Alfredo began studying Communication at night, while during the day he continued helping in the family business. That pioneering Institute of Journalism, founded by Matilde Pérez Palacio, had among its teachers the notable journalist Sebastián Salazar Bondy and the professor Jorge Puccinelli. Alfredo Kato remembers that he was a colleague of Alfredo Vignolo, another prominent journalist.

“In 1962, a competition was presented to be an editor for, published by La Prensa . Many of us showed up, Guillermo Thorndike made us pass three tests and I managed to enter with Alejandro Sakuda.” Later he was editor of La Prensa , where other Nikkei such as Ricardo Fujita, Pedro Shiguemoto, Julio and Enrique Higashi worked. There he was in charge of judicial and political issues and, finally, the entertainment pages that interested him so much since he was a child.

“I remember having to go to the airport to wait to see if someone important was arriving so I could do an interview,” recalls Kato, who as a reporter learned to take risks to get exclusives, to plot to assume greater responsibilities at the newspaper, and to do critical journalism. when he began to dedicate himself to the show. “On one occasion, I traveled to Mexico and stayed a month, from there I began to send notes and interviews with great artists of the time.”

television criticism

But if something identifies Alfredo Kato's journalistic career, it is television criticism, which began in the supplement 7 Días, of the newspaper La Prensa , where he had the column “Who TV.” Then he joined the newspaper El Comercio in 1984, a time when the newspaper made a leap into modernity with the off-set and the computerized system. There he published his famous column “El mirador”. The director, Alejandro Miró Quesada, told him one day: “Do you know what the first thing my wife reads in the newspaper? “He reads his column aloud to me.”

Such was the impact of his column that his positive or negative comments had great influence, despite its brevity. To this day he is remembered by many journalists and critics who have highlighted his honorability, ethical commitment and seriousness at all times, which earned him the affection and respect of artists. He could write about cinema, art, music, advertising or theater, without leaving aside the international level.

“We have always maintained that the main element of every radio or television program is the script, and that said media should worry about forming their respective teams of scriptwriters, to raise the level of their programs,” he wrote in his column that appears It was published until the 2000s, along with a letter from the reader in which they addressed him as “Señor Mirador.” In 2004 he retired, after having been editor of the entertainment pages and having taught a profession that today seems scarce.

Learned lessons

Alfredo Kato does not have a cell phone. A few years ago he maintained a personal website but now he has moved the contents of his old column to Facebook, where his daughter defines him as a “lifelong journalist and promoter of good journalism: accurate and precise. “Fan of Japanese cinema, old movies and musicals.” Talking to Alfredo is like going back easily to a past where journalism enjoyed elegance.

Today, that seems to be the main lack of times without time to research and write formally. Gone are the customs of making newsrooms a place of learning. Kato remembers the famous “little school” of Guillermo Thorndike, in La Prensa , who gathered the editors and made them read their published texts aloud so that they could identify their errors. Travel was also a means of learning, especially when it became difficult.

In an article published in Perú Shimpo , where he was a collaborator, he remembers: “they assigned me to go and report on a Faucett ship that had been lost in the central jungle, in La Merced, San Ramón, etc. We journalists collaborated in the search and every morning we flew over the area, trying to locate something that shined below, among the thickets. And when the plane was found on the peak of a hill, we had to help carry the bodies of the victims.”

Nikkei journalist

Kato is among that select group of leading Nikkei journalists, along with his friend Alejandro Sakuda, who recently died, Ricardo Fujita, Pedro Shiguemoto, Samuel Matsuda, Félix Nakamura, among others. Although he clarifies that he never felt different treatment for being Nikkei, he always felt attracted to Japanese culture and its values. One of them may be solidarity. He remembers that on one occasion he met Juan Makino Tori, a folk singer known as “El samurai del huayno.”

“He had a brother in Japan and I didn't know anything about him. As I was a correspondent for a magazine in Japan, I wrote his story and helped him look for him. He was very happy to know that he was alive but they never met again.” This small anecdote describes in full Kato, who used journalism in a noble way, although his criticism was greatly feared, and who in his last years as a columnist recommended in the pages dedicated to television, not to let children watch it.

“Many programs violate poorly formed consciences, impose prejudices and fuel unhealthy passions or, failing that, abuse their trust, through the tendentious presentation of the facts.” Alfredo Kato, who was also a journalism teacher, prefers not to watch current television and from television journalism he rescues some names, but maintains a critical streak: “today journalists have everything, but they must focus on the news, not on the "what could have been."

Sitting in front of a cafe at the Peruvian-Japanese Cultural Center, friends and acquaintances passing by keep stopping to greet him. From that corner of prestige and humility, Kato is happy about the union that the Peruvian-Japanese colony has maintained and the valuable endeavors that are carried out for culture. “Being Nikkei is much more than being of Japanese descent,” he noted in an interview, it is “bringing out the best of both cultures” 1 . Kato is a Nikkei through and through.

Note:

1. Interview - Alfredo Kato: " What does Nikkei mean to you? " (October 7, 2005, Discover the Nikkei)

© 2019 Javier Garcia Wong-Kit