Yamauchi for the most part left playwriting behind her in the last decades of her life, devoting most of her efforts to writing a series of semi-autobiographical short stories, including “McNisei,” about a group of aging Japanese Americans who meet at the local McDonald’s to have coffee and share gossip, jokes and painful truths.

She wrote the script for a documentary, Nurtured by Love, about Dr. Shinnichi Suzuki, inventor of the Suzuki method of music instruction. Los Angeles Mayor Tom Bradley honored her with a “Wakako Yamauchi Day” proclamation from the city, and she and my mother traveled to China together with a Japanese American tour group.

They also worked together for a while screen-printing t-shirts in a downtown L.A. factory. In the late aughts, I went with Yamauchi to buy a computer and then gave her lessons in using it; she was grateful over not having to completely retype manuscripts anymore, but understandably nervous that she’d be obligated to spend more time producing new work. With the rise of the web, I tried many times to convince her that email would be a great boon to her in communicating with all those interested in her and her writing—plus she would have the ability to do research right at her own desk—but, wary of surrendering her privacy, she steadfastly refused to connect to the Internet.

She gave up driving at night, and then eventually gave up driving. Never one to venture too often or too far from her two-bedroom home on Halldale Avenue in Gardena, it became even more the center of her universe. As flat as the Imperial Valley, Gardena had been slowly changing—apartments were popping up everywhere, encroaching from all sides, but Yamauchi never complained. After a childhood of having to move every two years, and an adolescence marked by her forced “evacuation” to Poston, it was surely enough just to have a permanent home.

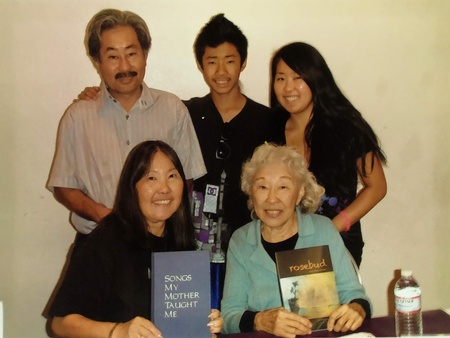

Between the trio of camellias by the front door and the swimming pool in back that had once served as a practice pool for a troupe of aquatic entertainers, Yamauchi retreated further and further into old age, coming to depend more and more on her daughter Joy—who lived with her husband, Victor Matsushita, and the younger of their two children in nearby Torrance—to take her to the supermarket and otherwise provide for her needs.

In one of those twists of fate that at times upend the natural order of things, Yamauchi outlived her daughter. Over the course of two years, whenever I would see Joy, I would be alarmed to find her progressively thinner and more drawn, her movements like those of a woman of advanced age. Determined, it seemed, to publicly dismiss her symptoms as nothing more than age-related arthritis, she refused to see a doctor until family members pressured her into doing so. By then, it was too late—she was diagnosed with terminal lung cancer. Admitted to Harbor-UCLA Medical Center in Torrance, she lay in a bed, hooked to a respirator and unable to speak, until she died in January 2014 at age 58.

At the time of Joy’s death, Yamauchi, then approaching 90, was already struggling with her short-term memory, and a mind that would sometimes wander and then loop back into an anecdote or observation that she had related only moments before. It was clear that she could no longer live on her own. While Joy’s daughter, Alyctra, who had recently graduated from college, was staying with her, Yamauchi left a pot of boiling water on the stove in which she was heating up a stone to warm herself in bed; Alyctra discovered the pot in time, about to burn, with all the water boiled out. She made the decision to move into Yamauchi’s house in Gardena with her fiancé to take over as her grandmother’s caretaker. They were joined there by Alyctra’s brother Lucas, still in high school, who most likely wanted to escape the troubling memories of his mother that pervaded the house in Torrance.

I wondered how Yamauchi would survive her daughter’s untimely death, but somehow, she soldiered on. Perhaps it helped that her mind was wandering a bit, or maybe the stoicism she had acquired as a child growing up in the desert just kicked in. She would pass hours doing the word-search puzzles that Alyctra brought her, which must have given her at least some peace of mind. I never got the impression that Yamauchi was afraid of dying—she seemed to accept, as well as anyone can, the immutable terms of living—another dividend of having grown up in such inhospitable surroundings. When she was not quite 60, she wrote the following to me about a trip home to L.A. from San Diego:

“The sun was setting as we started home. It stained the distant hills and the cluster of condo walls with a pale yellow light. I thought I would like to have a house facing the western sky, and have my evening meal watching the November sun edge into the gray sea. I felt sublime, thinking this, that I was part of the scheme of the universe and at that perfect moment, I would gladly have died. But, of course, I didn’t. And the moment passed.”

And this, from about 10 years earlier:

“And last Saturday, I went to Death Valley and saw that ancient land…the lava formations from billions of years ago…the salt beds of long dead lakes, sand mountains, shale mountains, granite mountains, and a strange alien desert. Surreal. All of man’s best efforts are only straws in the wind. So why should I scurry around (like a prairie dog) tryna put square pegs in round holes…tryna leave footprints to say I’ve passed this way. What does it matter? It doesn’t matter. One print more or less does not alter the surface of the earth.”

In her twilight years, Roberto and I would celebrate her birthday each October by taking her out to a Japanese restaurant near her home. Each successive autumn, when we would pull up at her house, Yamauchi would be dressed and ready to go, and once we arrived at the restaurant, we would escort her inside like attendants fussing over royalty. If the waiter or waitress happened to be from Japan, Yamauchi would order in Japanese, and, if there was any Japanese writing about, she would translate it for us, explaining whether the characters were the easier, syllabic kind or the more difficult, symbolic ones.

She once explained to us the meaning of her name, Yamauchi, as home (“uchi”) in the mountains (“yama”). Her daughter’s married name, Matsushita, she added, means “under the pines,” and Nakamura, the name she was born with, translated as “inside the community.” It was clear that her connection to Japanese culture ran deep—that even though she was a native Californian, she remained, in many ways, more Japanese than American.

But the most memorable part of those dinners was listening to her describe her stark and difficult childhood. That’s when I heard many of her stories of back-breaking farm work, reading by kerosene lamp, making do with dirty drinking water and facing opprobrium at school when her English failed her. Even with her short-term memory ebbing away, her long-term recollections remained exceptionally vivid.

In the spring of 2018, Yamauchi suffered a fall and fractured her hip. Roberto and I visited her in June at the chaotic convalescent facility in Torrance where she was recovering. By then, unable to walk, she had grown increasingly frail, and her appetite more and more tentative.

We found her sharing a three-bed room with a feisty black woman in a wheelchair who was facing a maelstrom of serious illnesses. Yamauchi was in the bed by the window that overlooked a dreary alley but at least afforded a view of the sky. Over and over, with the eyes of an artist and the mind of a writer, she would note how the afternoon light would go from dark to light and dark again as the clouds came and went, before her attention would return to the foam pillow between her legs that was preventing her hip joints from moving. Each time she felt the pillow, obscured by a blanket, she would wonder anew what its purpose was, before her mind refocused on the sky, its ever-changing brightness a metaphor for life’s endless sequence of pleasure and pain, and a reminder that the world was still in business, indifferent to her own helpless confinement. Even in that bleak setting, she found a way to see the beauty in the order of it all.

A nurse came in and remarked to us how much she envied Yamauchi’s teeth; all her own and miraculously uncompromised by age. We said our goodbyes and left the facility, the last time we saw our friend alive. After a number of weeks in the hospital, she went home again and received hospice care until her death in mid-August.

Yamauchi was cremated soon after, and commemorated in October 2018 at a memorial service at the Japanese American National Museum in L.A.’s Little Tokyo, where her papers and manuscripts reside. A fitting epitaph for her might be the last paragraph of her 1988 essay American Dream, in which she succinctly summarized the camp experience:

“Some say they had a great time in camp. There were soft ball games in dusty summer evenings, movies in the fire break (we carried our own collapsible chairs), talent shows—someone always sang ‘Don’t Fence Me In’—dances, Sadie Hawkins nights, and even here, forsaken as we were, Boy Scouts worked for their merit badges and on holidays marched proudly with Old Glory fluttering high in the yellow air. There was always someone to love, someone to hate, someone to envy. Lifelong friendships were made as well as lifelong enemies. And there were the flaming desert sunsets and incredible mornings—cool and crisp, forever promising renewal.”

If Yamauchi was able to find renewal in the dusks and dawns she saw through a barb-wire fence, then perhaps we can find a measure of it for ourselves, in both her life and her art.

© 2019 Ross Levine