So coming back to San Jose, you resettled back here?

Yes.

Was the reason because your parents were already familiar with it or did they just feel like it would be better to come back? Or do you know why they chose —

I think they were familiar with it and we had farm equipment that was being held by a very good family that helped us. It’s not that they didn’t use it, so they in turn benefited some, using the equipment.

But they held onto it for you.

Yes.

They were really good people. But you lost the house though that you were in?

Oh yes. The house that we lived in, I don’t know what happened. But when you start building a house, a lot of help comes from your friends and relatives. So they helped build the house that I remember, and that house travelled quite a bit. They put it on wheels and towed it over about half a mile through the fields and then situated there. And then we stayed there for probably about three or four years and then we moved again. Same deal. Put the house on wheels and moved it across to where Fry’s Electronics is on Brokaw. We were farming that area just when the war started.

And coming back to San Jose, what do you remember about those first few months? Where did you live?

Well, it wasn’t really nice quarters but my auntie, dad’s older sister, had property and they had a nice house, modern. And they had a workers’ house and that wasn’t very nice, but I think we might have spent around two months before they found a place to buy and continue farming.

Wow, they got on their feet pretty quickly.

Yes.

Do you remember, now that you were in high school, coming back and being a young teenager, do you remember any backlash or discrimination that faced you or your family?

Not, hardly any discrimination at school, but I remember this one thing that I guess we had homerooms and the first fellow I met, in fact I ran into him last year sometime. I really think he helped the Japanese a lot. Like my family, my second oldest brother was involved in sports and this fellow was a basketball player. And in fact he did real well at San Jose State. But anyway, he turned out to be the most nicest person. And in school, I’ve never heard of anyone having problems with discrimination. So outside of school, I recall we went to the movies, I guess, with, it must have been three or four of us kids and I guess we did get some of those loud people calling us names. But that was the extent of it, yeah.

That was it. And a lot of people came back to San Jose.

Right.

So when you moved back here, were you still near Japantown?

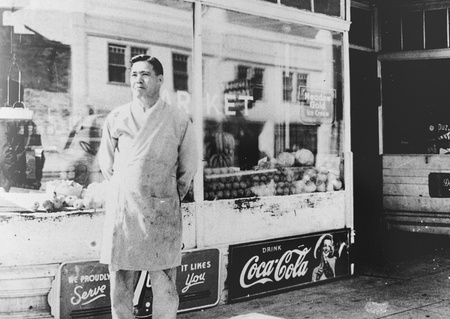

We were on Tenth Street, which is a couple miles from Japantown. And I guess my uncle, he’s the one that bought the small grocery store. And he started the Santo Market.

So your uncle was the one.

Yes. I guess he didn’t want to farm anymore.

Because it was a natural link between farming and then opening a grocery store for him?

Yes.

This was which uncle? On which side of the family?

My dad’s younger brother.

And so where was the first original market?

At the corner of 6th and Jackson. It was owned by this Filipino man and a lot of the products were not for the Japanese people but my uncle bought the business, and then after a few months moved over to a larger space right next door. And he fixed it up to sell regular groceries. Japan import items were very scarce then. But I guess eventually things like soy sauce and rice we had to get on the list for. Not rations, but to able to get some products to sell. Even rice was sort of scarce. At that time, I don’t know if you heard of, they had these coupons for meat and sugar and different things. And that was a hassle I would say.

Right. So how did your uncle, as far as you know, get all these items? Like how was he able to get his inventory to sell?

At first, I’m not sure. But the Japanese items, we then started seeing these Japanese wholesalers come around and they were handling whatever they had available. I guess the important things were shōyu, the soy sauce, and rice. I remember even the rice wasn’t too plentiful. And especially the kind of rice the Japanese like, the sticky California rice. I guess they brought in a lot of rice from Arkansas. And I do recall, when I started to help him, we had to take the truck to the warehouse. And these were 100 pound bags of rice. And we loaded onto the pickup and back into the store warehouse. So it wasn’t for anyone with a bad back, I’ll tell you that.

How old were you when you started helping?

I think I did a little bit when I was probably around a senior in high school. So 17, 18.

And I’m assuming that it successful from the start, right? Was he one of the first people to open, re-open a grocery store?

No, actually there was Dobashi market. They were open from back in 1910 or ‘15.

So, talking a little bit more about the market; it’s been in your family this whole time. So your uncle had it, and then when did that get passed on to you? When was that transition?

Well, let me go back. My uncle George had adopted my older brother, since he didn’t have any children. His name was Roy. And then I don’t know how I got caught in this, but I had got caught in the draft. Went to the military for two years.

What year was this?

This was the Korean thing there, 1952 to 1954.

Oh wow. So you served in the Korean War?

You might call it that. For every one out there, there must be about twenty back. I’m one of the twenty in the back. But anyway the Korean War there, I guess they had this draft. I started at San Jose State but then I must have messed up and I dropped off figuring the draft was gonna get me, and actually yes, in 1952 I was drafted. And I served two years.

I guess it was during that time that my uncle decided to build another store, since the other Japanese stores were rebuilding, too. I guess Dobashi market they were here, but then, we were here, but then they moved right almost next door. So my uncle decided to look for something that he liked and he did find this lot on the corner of Sixth and Taylor. And well anyway, my older brother, he wasn’t quite an architect yet, but he did the drawings for the store. For the new store. So that was in 1954 and it opened up in 1955. So it was about at that time that I was pretty much getting involved with helping out.

I see.

And I guess there had to be someone that could take care of the meat department. So I went to business friends, they had a butcher shop and he pretty much drew some plans on how to do this. Breaking down the meat for selling and things. So that was back in ‘55. And that was a new experience. And I think that we had some help from these Chinese people that had one of the busiest meat markets in town. It was called State Meat Market. And I got to know them because we used to buy meat from them. And they were very good about showing me different tricks and stuff.

So when you came back from the service, did you return to school at all or did you just go straight into working?

I went straight into working. That was something I wonder about. I probably should’ve gone to school. But didn’t.

What were you planning on studying or what interested you in school?

Well, nothing particular, so that was another problem. I didn’t have any plans of what I might like.

Now I’m curious about the impact of being incarcerated for your family and your parents. After the war was over, did your parents ever talk to you and your brothers about anything or did they just kind of stay quiet?

I think they were more of a stay quiet type of people. And I guess the word, shikata ga nai [it can’t be helped] I guess, what can you do? Yeah.

When you received your redress and the Civil Liberties Act passed, what were your feelings about that?

Oh wow, let’s see. I felt that especially the older folks who suffered the most, a lot of them were gone already. And I thought that was too bad and actually, the $20,000 especially to the older folks that lost so much property anyway was insufficient.

That wasn’t enough.

Yeah. And this doesn’t concern us but a good friend of ours was from Peru and I thought, “Boy, they got it worse!” Because they actually used some of the internees for prisoner exchange. That was horrible.

Are you speaking about Art [Shibayama] by any chance?

Art, yes. We got to know him pretty well.

Are there any other thoughts, anything else you want to share about your experience and reflections on this?

Well, I think the hardest hit were the Isseis, they lost so much. And the next group, being the people that were in college or ready to go to college that got disrupted by not being able to continue right away. And then in my grade level it wasn’t interrupted too badly. We went on. And most of us I guess handled the change pretty well. We didn’t miss out that much education in camp. I think we must have had pretty good teachers and all.

We continue our interview with Helen Santo >>

*This article was originally published on Tessaku on September 1, 2019.

© 2019 Emiko Tsuchida