The life of George Yamaoka, a Japanese American lawyer who was appointed by the Allies to defend accused Japanese war criminals after World War II, represents an interesting variation on the Nisei experience.

Yamaoka was born in Seattle on January 26, 1903. His father, Otohiko Yamaoka, was a Japan-born lawyer and community leader. As a youth, the senior Yamaoka had become one of the youngest men ever elected to the Diet. After being imprisoned for treason for his involvement in a conspiracy to assassinate officials in Shizuoka, he spent ten years in prison before being released through the intervention of allies. He then emigrated to the United States, became a labor contractor, and was heavily engaged in bringing over workers for labor on James J. Hill’s great Northern Railway. In later years, after exclusion of Japanese labor ended his contracting business, Otohiko Yamaoka distinguished himself as proprietor of the Tōyō Trading Company and of a local Japanese newspaper, Shin Nihon (New Japan), and he served as President of the Japanese Association in the state of Washington.

George Yamaoka (he is not to be confused with the California Nisei baseball star of the same name) was the oldest of Otohiko and Jhoko Yamaoka’s six children. George’s younger brother and sister, Otto and Iris Yamaoka, would each become known as screen actors who appeared in multiple short roles in Hollywood movies of the 1930s.

After graduating from Seattle High School, where he starred in athletics, the young George attended the University of Washington. There he served as treasurer of the Cosmopolitan Club, an Asian American student organization at the university. In 1926, George visited Japan, and later served as secretary to the Commissioner General for Japan at the Philadelphia Sesquicentennial exhibition. Around this time, he enrolled at Georgetown University Law School. While at Georgetown, he served as business manager of the Georgetown Law Review.

He received his law degree from Georgetown in 1928, and thereafter moved to New York, where he served as secretary to Hiroshi Saito, New York Japanese consul (and future Japanese ambassador to the US). In 1930 Yamaoka accompanied Saito as part of the Japanese delegation at the London Naval Conference. While in London, Yamaoka served under future consul Kaname Wakasugi in the press section of the Japanese delegation. Yamaoka’s fluency in Japanese and English and his writing skill won him admirers. He would later appear in a WMCA radio round table in November 1934 in New York devoted to the negotiations.

In 1931 Yamaoka became the first Japanese-American to be admitted to the New York State Bar. (Apparently the state Bar Association was not certain whether to admit people of Japanese ancestry to practice, despite Yamaoka’s American citizenship and legal training, and exposed the candidate to rigorous questioning before its Committee on Character and Fitness before finally admitting him).

Once admitted to practice, Yamaoka joined the law firm of Hunt, Hill & Betts, an admiralty law firm which handled multiple cases for Japanese shipping firms. In 1933, he married a French woman, Henriette d’Aurioc, and in the next years lived in North Hempstead, Long Island. The young Yamaoka proved to be a capable lawyer. In 1938 he attracted public notice when he won a large damage suit in the Federal Court of Appeals on behalf of the Japan Storage Battery Company against the Philadelphia Electric Storage Battery Company. The same year, when the New York Buddhist Church sought to buy a property on West 94th Street, Yamoaka handled the transaction. In 1940 he was made junior partner in the firm.

During the prewar years, Yamaoka was named president of the Tozai club, the exclusive Japanese club in New York, and enjoyed close connections to the New York Japanese consulate and to the pro-Tokyo business community.

In December 1941, in the aftermath of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, he lost those connections, and the business with Japanese firms that had sustained his law practice. Perhaps as a result of his close Japanese connections, Yamaoka seems to have kept rather a low profile within the community during the war. He briefly joined with Larry Tajiri and T. Scott Miyakawa as a sponsor of the Committee for Democratic Treatment of the Japanese (ancestor of the Japanese American Committee for Democracy) and worked for some weeks with the committee’s community welfare section, trying to find jobs for Japanese Americans displaced from employment by the war.

However, he appears not to have been an active participant in either the JACD or of the New York branch of the Japanese American Citizens League, founded in 1943-44. The one indication of his involvement was a 1943 letter to the War Relocation Authority’s New York office expressing interest in fighting a proposed alien land law imposed against Japanese Americans in Arkansas.

Following the end of the war, however, as the War Relocation Authority closed its doors, Yamaoka would help organize The Greater New York Citizens’ Committee for Japanese Americans. He also helped found New York’s Japanese American Association and would later serve as its president. (Both Otto and Iris Yamaoka, who had been confined at Heart Mountain during World War II, moved thereafter to New York, presumably under brother George’s sponsorship).

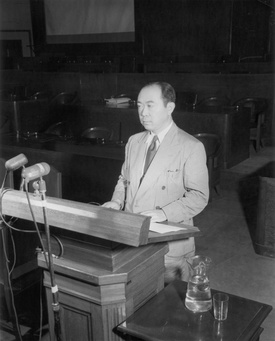

In 1946, at the request of the Japanese government, Yamaoka was invited by General Douglas MacArthur, the US proconsul in occupied Japan, to come to serve as counsel general of the American defense section at the Tokyo War Crimes trials before the International Military Tribunal for the Far East. (He joined his brother Sergeant Carol Yamaoka, who was serving with the occupying U.S. Army).

As a practicing American attorney, Yamaoka was able to coordinate the work of the Japanese defense attorneys with the American military and civilian lawyers assigned to act with them. While he was initially appointed a part of general defense staff, and not assigned to individual defendants, Yamaoka served as American Associate Defense Counsel for Shigenori Togo and American Associate Counsel pro hac vice for defendant Koki Hirota, a former premier and foreign minister, and also joined in the defense of former prime minister Hideki Tojo and other high-ranking Japanese war crimes suspects. The defense challenged the legality of the tribunal, arguing that it imposed ex post facto law on the defendants in the form of crimes against peace and crimes against humanity, that judges drawn from Allied nations could not guarantee a fair trial for the defendants, and that Japan’s war had been in self-defense after suffering from economic embargo. The judges rejected these arguments.

Interestingly, Yamaoka returned to New York before the international tribunal rendered its final judgment. Upon his return to the United States, Yamaoka stated publicly his belief that the accused enjoyed a fair trial, but did not feel that international law covered the trials. When he sought to return to Tokyo in order to be present for the final verdicts, he was denied permission to return as an attorney. Instead, Yamaoka registered as a foreign trader in order to attend.

When Hirota was found guilty and sentenced to death—the only civilian to receive the ultimate sentence--Yamaoka and his colleagues were outraged. Yamaoka believed Hirota should have been acquitted or received a lesser sentence, considering his role as a civilian and his inability to control the military that essentially ran the government, and in that way “took the fall for Japan’s civilian leaders.”

When Hirota, former Premier Hideki Tojo and five other defendants appealed their death sentences to the U.S. Supreme Court, Yamaoka was invited to join the defense team at the last moment. In December 1948 he flew to Washington DC to participate, and presented his views during oral argument. It was the first time that a Nisei attorney had ever argued before the high court. Yamaoka argued that even if the sentences had been handed down by an international tribunal, the Court had the right to examine the constitutionality of the verdicts. “So long as there was American participation in this trial, to the extent of that participation the safeguards of the Constitution must apply. No American officer can act in contravention of those safeguards.” The Court refused to intervene or grant appeals, and the condemned were executed on December 23, 1948.

After returning to New York, Yamaoka rejoined Hill Betts (now called Hill, Betts, Yamaoka, Freehill & Longcope) and worked with its offices in both New York and Tokyo. As his junior partner Francis Sogi recalled in his memoir Kona Wind:

“In the early 1950s, as George Yamaoka and I were the only lawyers able to speak both English and Japanese and were the only ones who were qualified to practice in both jurisdictions, we attracted a lot of business from American companies eager to do business in Japan. We represented some of the leading firms in Japan, some from pre-war days, with a client list that included Mitsubishi International, C. Itoh & Company, Marubeni-Iida, Nissho-Iwai, Toyoda Tsusho and Toyota Motors, Kawasaki Heavy Industries, Kawasaki Steel, Kawasaki Shipping Company and many others. We also represented some of the major city banks such as Bank of Tokyo, Mitsubishi Bank, Mitsui Bank, Tokai Bank, Daiwa Bank, Fuji Bank, and others.”

In addition to his law practice, Yamaoka occupied leading positions in a large number of Japanese financial institutions and companies with branches in the USA. For example, in 1955 he was one of the founding directors of the Bank of Tokyo Trust. He also served as president of Nippon Kogaku and chairman of the Yasuda Fire and Marine Insurance Company.

Yamaoka remained active in other activities. In 1960 and 1961, he traveled to Washington DC to testify before congressional committees. The following year he published an essay in the anthology Doing Business Abroad, on foreign investment in Japan and Japanese import and export regulations. In 1968 Yamaoka was decorated by the Emperor of Japan with the The Order of the Sacred Treasure (Third order). In his later years, Yamaoka divided his time between New York and Fort Lauderdale, Florida. In November 1981, while riding in a taxicab in Manhattan, he suffered a heart attack and died. His collected documents from the Tokyo War Crimes trials are housed at the Georgetown University law library.

George Yamaoka’s life and career seem paradoxal. Despite his West Coast birth and Japanese ancestry, he was able to integrate himself into mainstream life and business circles in cosmopolitan New York, and made use of connections with Japan (his father’s abandoned homeland) to support his law practice. At the close of the US-Japanese war, he was appointed by the US government to help defend the Japanese officials taxed with responsibility for that war. He tried vainly to preserve them from execution by a stirring disquisition on Constitutional law to the U.S. Supreme Court. Following his service in Tokyo during the US occupation, he built a lucrative set of business relationships with Japanese and American firms.

© 2019 Greg Robinson