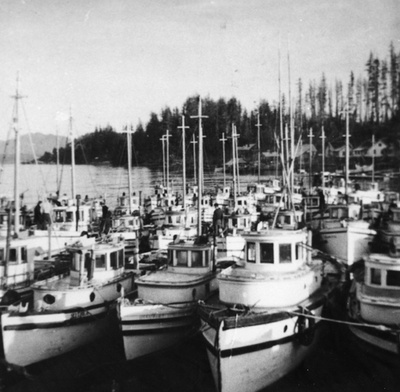

Shortly after the beginning of the war with Japan, the Canadian government ordered all Japanese Canadians living within 150 kilometers of the coast to “evacuate.” Kazuko’s family were given only twenty-four hours to leave their home. She remembers her mother telling her to quickly pack her own clothes. The police were at the door waiting for them to leave, so there was no time to waste. It happened so quickly they had no chance to ask friends to take care of their property or any of the things they left behind, so they lost everything. She says, “All our property and goods were confiscated: house, boat, everything. The RCMP were there, so although father was shocked at what was happening to them, there was nothing he could do.” Later the Canadian government sold off the property of the uprooted Japanese Canadians and used the proceeds to help fund the internment camps where they were being held.

Kazuko’s father was one of about 700 Japanese Canadian men incarcerated in POW camps in eastern Canada. Kazuko remembers watching him being taken away by the RCMP. The police gave them the impression that it was just a temporary separation, but the family would not see him again until years later when they boarded the General Meigs to be exiled to Japan after the war. Kazuko does not specifically know why he was one of those sent to the POW camp as he never talked to her about it. The usual reason given for being sent to a POW camp rather than an internment camp was resisting the evacuation order.

At first, Kazuko, her mother, and her siblings were held for three months in a livestock building at the Pacific National Exhibition (PNE) grounds in Vancouver. It had previously been used for holding livestock. It smelled like manure and the conditions were awful. She says, “If you became sick, there was no doctor. It was fenced all around and guards were standing outside so we couldn’t go out, and people could not come in to visit. The food was terrible, but if you didn’t eat what you were given and didn’t go to the common eating area at the scheduled time, you couldn’t eat.”

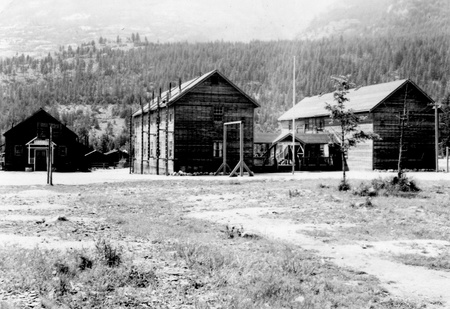

Finally, they were sent by train to the Bay Farm internment camp. Kazuko was quite frail as a child and became ill on the train from Vancouver to Slocan City. It was not a real passenger train but consisted of freight or livestock cars with seats put in, and moved very slowly. When they finally arrived at Bay Farm, they first lived in an old apartment while the houses were being constructed. Eventually they moved to a house on Sixth Avenue which consisted of only two bedrooms and a kitchen. The houses were built in rows, and each house had an outside toilet.

There was a rule in the camp that, if you had at least seven family members, you were allowed to have a whole house to yourselves, whereas if you had less, you had to share a house with another family. Kazuko’s family at the time consisted of the mother and four children, so, in order to qualify for their own house, they borrowed the names of two children from a larger family, the Kamitakaharas. Actually, the “borrowed children” continued to live with their own family, so it was nothing more than a convenient arrangement on paper that enabled Kazuko’s family to have their own little house. It seems that Kazuko’s family had quite a strong relationship with the Kamitakahara family, and she remembers that after the war the Kamitakaharas moved to Alberta to work in the sugar beet industry where they did quite well economically. One of the sons later moved back to Vancouver and started a prominent insurance company.

There was no running water inside the buildings in the camp. The water tap, like the toilet, was outside. During the cold winter season they would put a bucket of water on the stove at night to keep it from freezing. They used some of this water to make breakfast in the morning. The rest they used as a toilet during the night, and then took it outside for disposal in the morning. Kazuko remembers there was lots of snow, but they were just kids so didn’t mind as much as the adults. However, it was a much colder climate than what they were used to in Vancouver.

It was hard to eat properly, especially at the beginning, although they could buy some basic foods at the government-run grocery store. It was necessary for the internees to share their various skills and improvise in order to live. For example, carpenters would lend their skills to families who needed to repair or renovate their houses. “We had to make everything ourselves,” says Kazuko. During the first summer they started raising their own vegetables. Later the internees were able to set up a machine for making tofu, and also start a bakery. Eventually they even built their own public bath. Kazuko is still amazed at what they became able to do. Many housewives took sewing classes, among whom was Kazuko’s mother.

Kazuko does not recall seeing white people in the camps, except for a few teachers and police. Some teachers were Japanese Canadian, and some were white Canadian church teachers. The camp had a simple school building, and one teacher would teach two grades combined together in one classroom. She recalls, “The school building was cold, but we were kids so it didn’t matter to us.”

To be continued...

* This series is an abridged version of a paper titled, “A Japanese Canadian Teenage Exile: The Life History of Kazuko Makihara,” first published in The Journal of the Institute for Language and Culture (Konan University), March 15, 2019, pp. 3-20.

© 2019 Stanley Kirk