The 120 bowls in varying shades of yellow are being taken to camps where innocent Japanese-Americans were imprisoned during World War II.

Today, when many other people protest unfairness with loud demonstrations, Setsuko Sato Winchester is using quiet beauty to draw attention to one of the ugliest acts of racial discrimination in American history.

Setsuko has created 120 tea bowls in varying shades of yellow to symbolize “the yellow peril,” as Asians were once described. Each yellow bowl stands for 1,000 of the 120,000 individuals of Japanese descent imprisoned in camps during World War II.

“I wanted to do it in a way that was gentle, not hurtful,” she says.

Setsuko began in 2015 to “hand pinch” each tea bowl — meaning using her hands instead of a wheel to create it — after which she and her husband carefully placed the delicate yellow bowls in two big boxes in the back of their Land Rover to begin the journey from their Massachusetts home to each of the 10 main camps where Japanese were locked up.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt enabled the imprisonment of Japanese-Americans and resident aliens primarily living in Western states two months after the bombing of Pearl Harbor when he signed Executive Order 9066 to allow regional military commanders “to designate military areas from which any or all persons may be excluded.”

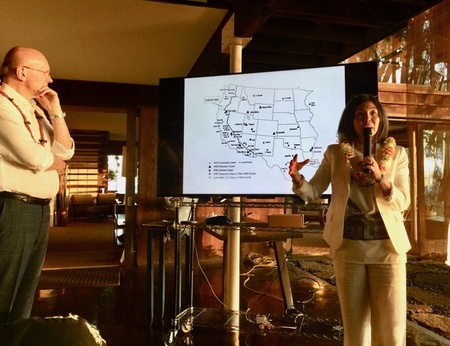

The Winchesters visited camps from Arkansas’ Jerome War Relocation Center, where some Hawaii residents were imprisoned, to California’s Manzanar and Tule Lake — the latter was the largest camp with 18,789 inhabitants including detainees from Hawaii.

At each site, the bowls were configured into a site-specific design to be photographed and then eventually packed up to drive to the next site.

Setsuko’s husband, Simon Winchester, is the best-selling author of celebrated works including “The Day the World Exploded: August 27, 1883 Krakatoa” and “The Professor and the Madman,” just released as a feature film starring Mel Gibson and Sean Penn.

Setsuko is a ceramicist and a journalist who was an editor and producer in Washington, D.C., on National Public Radio’s “Morning Edition” and “Talk of the Nation.”

Now the Winchesters are in Honolulu, where he is the keynote speaker Tuesday night at a summit on peace, global understanding and climate change called “Margins of the Sea” at the Liljestrand House on the extinct crater above Makiki, Mount Tantalus.

His role is secondary in Setsuko Winchester’s “Freedom from Fear/Yellow Bowl Project.” He has served as her driver, porter and assistant on the 18,000 miles they spent zig-zagging across America to take the bowls to the different Japanese imprisonment sites. He calls himself her “box hauler and spear carrier.”

On Monday, they visited Honouliuli Internment Camp in Kunia to photograph 16 of Setsuko’s yellow bowls in the ruins of what was once Hawaii’s largest and longest operating wartime incarceration camp (1943-46). No public exhibition of the bowls is planned.

“Setsuko’s yellow bowls bring a different approach to commemorate this incredibly dark and sad chapter in U.S. history,” says Japanese Cultural Center of Hawaii president and executive director Jacce Mikulanec, who arranged Setsuko’s visit to Honouliuli.

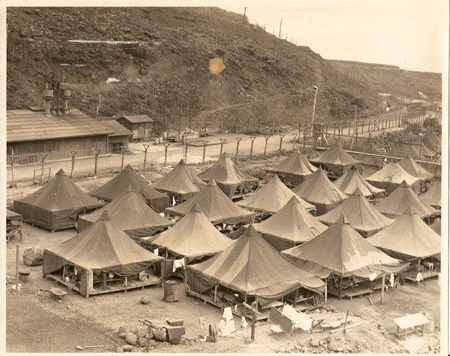

At the height of its use, Honouliuli housed 4,000 prisoners of war in tents and barracks as well 320 Hawaii residents, mostly Japanese-American and some German-Americans, rounded up with no evidence or trials.

In February 2015, President Barack Obama signed an executive order to make Honouliuli a national monument.

Honouliuli is distinctive for the amount of time it remained hidden from sight. When it was in operation, families who wanted to visit relatives were blindfolded when they boarded buses downtown so they would not know where they were being taken.

Not until 2002 did Jane Kurahara, a volunteer from the Japanese Cultural Center of Hawaii, uncover the location of Honouliuli camp by focusing on an aqueduct she saw in a photo and comparing it to features in old maps. She then confirmed the location by driving through the area. The aqueduct is still there today.

Mikulanec says there are tens of thousands of people who go by Honouliuli Gulch and have no idea they are meters away from a World War II internment camp. And he says, “On the neighbor islands, there is an unawareness of the imprisonment of Japanese-Americans. People still don’t know the internment camps were not just on Oahu but there were 17 different sites in the islands.”

Setsuko calls the 10 camps she visited on the mainland “concentration camps.”

Although the term is controversial, it is becoming more acceptable to describe the isolated, rural camps where innocent people of Japanese descent — 75 percent of them U.S. citizens — were forcibly taken. Often they were thousands of miles from their homes, locked up behind barbed wire fences patrolled by armed guards.

They were imprisoned because of who they were, not because of what they did.

The camps were referred to with all kinds of euphemisms, including relocation camps, evacuation camps or even pioneer camps — but most often internment camps.

But Setsuko says that’s inaccurate because internment camps were a different kind of camp run by the U.S. Department of Justice and the former U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service to detain “enemy aliens,” which is legal in the United States during times of war. The aliens were arrested, charged, given hearings and if they could not prove their innocence, they were held until they could be deported.

Operations at these internment camps were governed by the Geneva Convention, whereas the camps holding the 120,000 men, women and children of Japanese descent without legal recourse were run by the U.S. military and the War Relocation Authority with no oversight by the Geneva Convention.

Setsuko says she was drawn to bring attention to the camps through her ceramic bowls because of her own ignorance as a young student about what happened to Japanese-Americans during WW II. She grew up in New York City, the child of Japanese immigrants.

When a substitute teacher brought the book “Farewell to Manzanar,” to her middle school class for her to read, she and other students were astounded. The book co-written by Jeanne Wakatsukui Houston is about what she endured when she and her family were incarcerated at Manzanar near Death Valley. Setsuko said that she and her classmates had difficulty believing this happened in America.

She says her goal now is to make sure people don’t forget what happened to innocent people and to be mindful that such injustice could happen again in today’s climate, where we see children of immigrants crossing the U.S.-Mexico border being locked up, and in China, where 120,000 Muslim Uighurs have been forced into “re-education” camps one Chinese official called “boarding schools.”

Setsuko says such actions are always driven by fear.

“My story is hopeful, ” she says. “I am what everybody was scared about. I am about as scary as a yellow bowl.”

*This article was originally published on Civil Beat on May 14, 2019.

© 2019 Denby Fawcett