In June 2019, Discover Nikkei published an article of mine on the Nikkei community in the Netherlands and on popular reactions there to the Redress Movement. In it, I covered the life and work of Shinkichi Tajiri, one of the most prominent modern sculptors in the Netherlands and brother of Pacific Citizen editor Larry Tajiri. Thanks to the influence of my friend and mentor Greg Robinson, I have become fascinated with the life and work of the far-flung Tajiri family (read Greg's article on Shinkichi Tajiri here). After putting together that article, I had the chance to interview Giotta Fuyo Tajiri, the daughter of artists Shinkichi Tajiri and Ferdi Tajiri-Jansen, and speak to her about her own artwork and experiences with the Redress movement and the Asian American Theatre.

Giotta Fuyo Tajiri is an artist, sculptor, and author. She worked as a set designer for noted playwrights Philip Gotanda, Genny Lim, and David Henry Hwang before embarking on her own art career. Both in collaboration with her father and on her own, Giotta's work has been presented in numerous museums across the Netherlands. Her exhibit Hybrids premiered in 1999 with the L5 initiative in Roermond and was shown at the COBRA Modern Art Museum at Amstelveen in 2001. Recently, she co-published an edited volume on Shinkichi Tajiri, Universal Paradoxes, with Leiden University Press in 2015. She is currently the CEO of the Shinkichi Tajiri-Jansen Estate, and is responsible for maintaining the legacy and rights of the artwork for Shinkichi and Ferdi Tajiri.

Having grown up with a Japanese American father who experienced the camps, when did you become aware of the history of the incarceration?

GT: I knew nothing about it as a young kid. The first time I became aware of what happened to my father’s family was when we spent three months in Minneapolis in 1972. My father was asked to come and teach as a guest professor at the Art Institute. When I was fifteen I saw a documentary on television about the camps and what happened to Japanese Americans after the attack on Pearl Harbor. I think that was the first time I consciously remember learning about it. I was really disturbed watching that documentary and asked my dad why he still had his American passport, since he was now living in Europe. The attack on Pearl Harbor also marked his 18th birthday, and was a turning point in his life. He became upset and told me he felt the only way he could remain critical of the United States was to be a U.S. citizen. I realized much later that he was very outspoken about the unlawful incarceration of Japanese Americans.

While in camp he volunteered for the US Army in order to get out of camp. As he put it, he would rather take his chances in the Army than being locked up as were the Native Americans on the reservations.

After 11 months of training at Camp Shelby, Shinkichi joined the 442nd Regimental Combat Team and was shipped over to Naples, Italy in April 1944. On July 9th 1944 he was seriously wounded, and spent 6 months in a hospital in Rome. He was released shortly thereafter and reclassified to limited service. He left for Paris after the war on a G.I. Bill in 1948 to study art.

Growing up in Holland, I learned about the attack on Pearl Harbor, but what happened to the Japanese Americans and the incarceration camps was not part of our history education. The Dutch however had their own history with the Japanese when they invaded Indonesia, then still a Dutch colony. So when my father came to Holland, he still had the face of the enemy. When I was in high school, Shinkichi began to give me books by different authors from the Black Panthers, and this is how I learned about the Civil Rights Movement.

The first time I felt different was after we moved from Amsterdam to Baarlo, a Catholic village in the south part of Holland. We were the first kids there of a different ethnic background, which set us apart. I had a mother who was blond and Dutch, and a father who was Japanese American. It was never a question or an issue until we moved there and I became aware of our unusual family make-up. It hadn’t occurred to me that this was out of the ordinary.

What did Shinkichi think about the Japanese American community? Especially given he left the United States.

He left the US in 1948 and lived in Europe for the rest of his life. He referred to his decision as a self-imposed exile. He kept up with American news, arts, and politics through magazines and newspapers, and he always opened his house to visitors from abroad. He remained critical and outspoken on what happened to the Japanese Americans and other ethnic groups, and would get upset if people waved away the experience of the camps as if it was just summer camp. To him, being locked up as an American citizen without due process or evidence was an injustice, and he couldn’t understand why many Nisei kept quiet about this for so long. He collected books and films on the history of the Japanese Americans and the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, and now we have an extensive library on the subject.

Did you have a strong connection with your American family?

I always knew about my U.S. family. My grandmother came to visit us in Holland several times. There were a few occasions on which we met with our family in the US. The first time was in 1964-65 when my father was a guest professor for a year at the Art Institute in Minneapolis, and our grandmother came to live with us then. Our only family reunion was in 1981, when Shinkichi’s Friendship Knot was unveiled in Little Tokyo, Los Angeles. Shinkichi received the Key to the City by Mayor Tom Bradley for his contribution.

Because your father was from the United States and a Japanese American, did you always feel Dutch?

Not always, but I would not define it as such. We were different. Growing up with parents from different ethnic backgrounds, who were both artists, set us apart from the rural community we lived in. It was not until I was twelve years old that I met some ‘Indo’ girls (half Indonesian, half Dutch) and we immediately bonded and became friends. They were the people I identified most with, because they were the only ‘others’!

You became an artist as well. How was the art academy transformative for you?

I studied Costume and Set Design at the Rietveld Academy in Amsterdam.

The year before I graduated I decided to go the U.S. and investigate Asian American theatre. I started in New York and stayed with friends of Shinkichi, Steve and Takako “Taxie” Wada. Steve was an artist, but he was an accomplished dental ceramist too. Takako was a journalist and the English-language editor of The New York Nichibei, a Japanese American newspaper. She was an important figure in the Asian American civil rights movement.

Takako was the one who introduced me to people within the Asian American theatre community. I met several playwrights through her, such as Philip Gotanda, David Henry Hwang, and Rick Shiomi. Takako was the one who took me to the Redress hearings at Lincoln Center in New York City, and that was when I became introduced to the Redress movement. I went to Chicago to visit family, and on my way to California I stopped over in Denver to meet Bill Hosokawa. He knew my father’s oldest brother Larry Tajiri. Larry, along with his wife Guyo, was one of the leading Nisei journalist during World War II and the editor and columnist for the Pacific Citizen. Both Bill and Larry worked for the Denver Post as journalists. Larry was hired as a staffer at the Denver Post in 1954 and later he became the Post’s drama critic and entertainment columnist. He passed away in 1965.

Upon my arrival in the Bay Area I began to look for an opportunity to work in theatre. Someone told me to contact the Asian American Theatre Company in San Francisco, they were staging a play by David Henry Hwang called “FOB.” I met with Wilbur Obata and he gave me the opportunity to design the set for F.O.B..

I had brought a portfolio with me to show to people during my three-month trip. By the time I was ready to go back to Holland, I had collected some plays from playwrights that I had met during my trip. In order to convince my professors of my intent to graduate by doing Contemporary Asian American Theatre I had written up a whole plan. My thesis would be about Asian American history, and in particular that of the Japanese Americans. The plays I presented were F.O.B. by David Henry Hwang, for which I had already designed the set in San Francisco, For Bullet Headed Birds by Philip Kan Gotanda and Paper Angels by Genny Lim. I collaborated with Dutch directors and designed plays for two different theatre spaces in Amsterdam.

What did you take from your trip in the United States?

It brought a lot of clarity and raised more questions. The goal of my three month trip was in large part a search for my identity, and to connect with my Japanese American side. The thing that startled me was that there was still prejudice towards people of mixed racial backgrounds within the Japanese American community. Coming back to Holland I realized that my friends, of whom many were mixed, were the people I most connected with. They were my extended family.

You have other cousins that are hapa?

I have four cousins from my father’s sister Yoshiko who are Hapa. The Yonsei in our family are even more diverse in their ethnicity, and turned out be a beautiful eclectic, creative/artistic/literary/musical and socially conscious generation that I’m really proud of.

Do you feel being mixed is more accepted now?

Now it is more common. I remember my father telling me about an experience he and my mother had in 1965, when he was invited to a party for Playboy Magazine by his brother Vince Tajiri, who was the original photo editor of Playboy. During dinner the waiter came to my parents and dropped soup on my mother’s dress. My father saw it was intentional, and so they left. Shinkichi saw this as a clear statement of disapproval of them being an interracial couple, and decided to not come back.

In Holland, my own experience has been frustrating. In 1998, I was invited by an artist initiative to do a project in their space for the 400th anniversary of trade relations between Japan and Holland. I was a bit skeptical about this invitation, because I knew that the reason I was approached obviously had to do with the fact that I have Dutch/Japanese roots. I decided to accept the invitation so that I could address the issue of not being Dutch enough for the Dutch, but not enough Japanese for the Japanese.

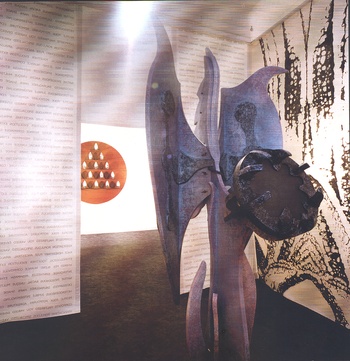

I started thinking about what it means to be of mixed ethnicity: How do I see myself? Definitely as a whole person and not half of one and half of the other. I came up with a project called “Hybrid: The Human Condition.” I decided to make a ‘sight and sound’ installation. I didn’t want to base it simply on ethnicity, because that is only one way of looking at it. People who leave their homeland to start a new life in another country bring their own cultural baggage, and to assimilate they adopt things from their new environment. The most positive outcome is that you take the best from both, and it enriches you as an individual.

A story of migration, in some ways.

Right. I wanted people to share a testimony, a story or an anecdote—in any language. I sent them cassette tapes, with a request to record their thoughts. I wanted to use the human voice as an instrument. Out of eighty tapes that I sent, I received an amazing score of 58 back. What was surprising was the diversity of the tapes. Some people took the direction quite literally, other people expressed themselves in a more poetic way. So I had these short, three-minute sound bites. But then my ideas changed. I decided I could not distort the voices and transform them into white noise. I had to leave the testimonies as they were. They were personal and touching.

I made the installation into an environmental piece, with a large sculpture in the center with nine speakers in it. Together with a musician, we made an underlying sound for the environment. If you walked near the sculpture you would hear the different stories coming out from the speakers.

It’s like a human diary, no?

Exactly. The installation was on exhibit for a month, from the 1st to the 31st of December 1999. And for me it was symbolic of going into a new millennium, where the only way we can survive as a human race is if we become hybrids. Whether as mixed race or mixed culture, we have to move forward. The world has become so small. It’s our collective responsibility to do right! The strength of being a hybrid is being able to bridge different identities, it broadens your view and makes you more compassionate. I have more empathy in different situations because I understand what it’s like to not fit in or be the norm.

There was recently an exhibit at JANM that profiled Hapas as well, by Kip Fulbeck. What are your thoughts on it?

I heard about the Hapa-project that Kip Fulbeck started. My cousin Chiori Santiago was in his first book, Part Asian, 100% Hapa. How great it is to find out that in different places, people are tapping into an awareness, and recording and documenting this. In my project I focused on the stories. The great thing about Kip’s books are the photo profiles. Unfortunately I haven’t had the pleasure of meeting Kip Fulbeck, but I know we have mutual connections.

How funny is it that my husband Terry is also Hapa and we now have a beautiful daughter Tanéa and son Shakuru, Hapa 2.0.

What is your next project?

Since my father’s passing in 2009, my attention has shifted to taking care of both my father and my mother’s legacy. It has become a full-time job. I’m very proud to say that both Shinkichi and Ferdi have their work on permanent display in the 20th Century Art department of the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam. Together with my sister Ryu and my daughter Tanéa, we’ve been busy with safeguarding, promoting, and keeping their work visible through exhibitions and publications. It would be great to bring my father’s work back to the US, and in particular Los Angeles, and for the Japanese American community to know of Shinkichi’s story.

© 2019 Jonathan van Harmelen