The prefecture of Kagoshima is located in the south of Japan, a group of islands from where more than 110 years ago a group of Japanese left for Peru, without imagining that in those distant lands they would find a new homeland for their descendants, a place so different but with some similarities that they now begin to see when they return to their country of origin.

Migration stories are often painful and cathartic. Perhaps for that reason, and because of the well-known reserve of privacy of the Japanese, many immigrants do not dare to tell them. Two years ago, the Peru Kagoshima Kenjinkai organization celebrated 100 years of founding (February 7, 1916) and 110 years of Kagoshima immigration to Peru, a date that is difficult to ignore in the celebratory activities.

“Among the various trades that the immigrants from Kagoshima in Peru learned, the one that stood out the most was baking. They also dedicated themselves to watchmaking, carpentry and hairdressing,” explains Gloria Yoshida, its current president. In recent years, they began relations with their peers in Brazil and this year they participated in the Kagoshima Global Kizuna Assambly, the first global meeting of the descendants of that prefecture, in which 20 countries participated.

Institutional history

However, there was a postponed project that the Kagoshimans did not want to miss and that already had a long queue: the preparation of a commemorative book with the history and activities of the institution, as well as other anecdotes of the “34 Kagoshimans who arrived in Peru without knowing the language or customs, but with their courage, sacrifice and effort they helped their families forward,” says Gloria Yoshida, a member of one of the 130 families that participate in this organization.

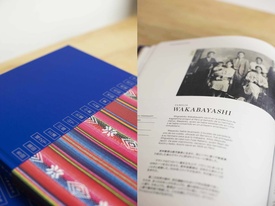

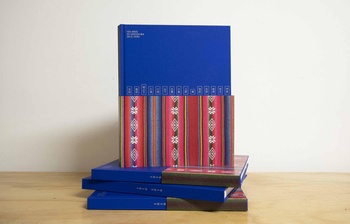

Young people from the same kenjinkai were involved in this work, who have undertaken this work with great enthusiasm and professionalism. “It has taken us six long years to get our hands on the book that we present to you today,”1 Gloria Yoshida said regarding the book “100 Years of Kagoshima in Peru 1916-2016,” in October of this year. Diego Yoshida was in charge of compiling the 34 family stories in the publication and Amanda Hirakata Miura carried out the editorial design.

“Initially, the idea was to compile only the life stories of the first migrants (isseis), based on the narration that their descendants could make. At this point, it was not very clear what format would be used for the life stories, but it was agreed that it should be quite free, to allow each family to tell what they considered important about the life of their grandfather or grandmother," says Diego Yoshida.

family exploration

Diego is a sociologist and during the three years of research he discovered many important events within the kenjinkai, so little by little, additional chapters were included. “Not only did the structure of the book change, but also that each family contacted linked us back to another one, so the initial goal of about ten ended up being 34 stories.”

Although most families live in Lima, there were some that were on the outskirts of the city. Diego Yoshida interviewed all of them, who considers that a trait that distinguishes them is the strong union, legitimized by records such as koseki and a series of values and customs that “are closely linked to our origins, perhaps more than we can imagine.” ”.

For him, making this book has been a good way to connect with his history and pay tribute to the legacy and cooperation within the community. “I think that to understand our position, the job we choose, the friends we have or our tastes, knowing our roots can clarify our way of thinking and perhaps help us make better decisions,” says Diego.

Shared inheritance

Many may think that the stories of Japanese migrants are the same. Although there are several points in common, the interesting thing about this book is in the narration that each family makes. “The union within the migrant group through meetings had tremendous cultural value. The meetings between the elders where they maintained the Japanese language, the tanomishi to mutually support the growth of local businesses, the reading of newspapers brought from Japan to share news,” says Diego Yoshida.

The direct account of the descendants also allowed him to know how this historical event is seen today. “Personally, I think that for new generations of Nikkeis, this work allows them to get closer to their family's history in a very enjoyable and accessible way. What was sought from the beginning is that the target audience would be the grandchildren themselves and that this work would serve to awaken that interest in learning more about their origins.”

That shared heritage became more evident when noticing that the majority of families in Lima that come from Kagoshima know each other, are related or are related. “The research for the book allowed us to connect two generations and open a space for conversation. There were several people who expressed their gratitude to us for encouraging them to sit down one afternoon to talk with the ojichan or obachan, and for the first time hear about the long journey their ancestors had to go through,” he points out.

Those little similarities

From Kagoshima, where he has traveled on a scholarship, like 27 other young people who benefited from the kenjinkai, Diego tells of some similarities that he finds in that coastal city crowned by the Sakurajima volcano and his native Lima. “I have been able to notice particularities between the surrounding cities, whether in the gastronomic field or music, for example. But I think the most visible would be the dialect or the ways of expressing oneself; what in Japan they know as Kagoshimaben.”

Amanda Hirakata, the book's designer and graphic editor, was in Kagoshima last year, and she saw those little details, too. The sweet potato, for example, which many in Peru consider part of their food culture, is also planted and consumed here and in more varied products: sweets, liquors and desserts. In addition, the fact that they are coastal cities also fosters some similarities. She says that knowing Japan helped her understand her parents more and better understand her Japanese origin.

“Kagoshima is a province, it is not a big city. Everyone here is very kind and careful. "They are considerate of others, as well as reserved, they do not show their feelings." For Amanda, who grew up in a home with very moderate and silent parents, being here made her understand her nature better. “My ojiichan had to experience things due to the impact of the war that led them to censor themselves, now everything is different but it is important to remember it,” he says.

The edition

Prepared in a table book format, the book “100 years of Kagoshima in Peru 1916-2016” was initially going to be a magazine, but the drive of these young people and the interest in recovering those family anecdotes led them to give it more scope. “Listening to each story from different perspectives is also interesting because everyone remembers things in their own way,” adds Amanda Hirakata.

For Diego Yoshida, finishing the book is just closing a chapter of a story that is “much more complex and interesting. When I read about the lives of migrants, I have that feeling that parts of the story are missing. I would like to continue the research from the Japanese point of view and in a much more academic way,” says Diego, for whom being Nikkei means “carrying two cultures within you. That is, having the opportunity to see the world in two different ways, and think from a much more complete vision.”

Valuing this facet is one of the objectives of the book, which links the Japanese and the Peruvian at the beginning of each chapter, with elements of its history and a beautiful finish on the cover and its cover, which resembles a pre-Columbian loom. Gustavo Hirakata, in charge of the illustrations, Toshihiro and Mitsuru Nakajima, for the Japanese translation, and Alfredo Yoshimoto, in charge of printing, participated in its edition. It has been a great honor for them to be able to deliver this publication to Satoshi Mitazono, governor of Kagoshima, as well as other prefectural authorities. Without a doubt, a milestone that adds to the rich history of Japanese migration.

Note:

1. “ Book presentation: 100 years of Kagoshima in Peru 1916-2016 ” ( Peru Shimpo , October 12, 2018)

Contact Yuri Sasaki, ysasaki_1969@hotmail.com , or Gloria Yoshida, kagoshima@kenjinkai.pe .

© 2019 Javier Garcia Wong-Kit