For many of the issei interned by the Justice Department during World War II, their years in confinement posed serious questions of loyalty and identity. Many had once strongly identified with the old country, and had worked to forge what Eiichiro Azuma has identified as a “shin-nippon,” or new Japan, in the New World. Yet their decades of separation from their Japanese homeland, and the arrival of a new Nisei generation during the 1930s, led many to rethink their allegiance. The New World was their new home, despite the institutionalized racism they encountered in the United States, and most did their best to live in the society around them.

Both before and after the war, some issei leaders sought to challenge the prejudice around them, and not only advocated for the nikkei community, but in the process built relations with other communities. One such individual was Katsuma Mukaeda. Although very little is written about him, his life as a community activist in the Los Angeles area should be studied closely.

Born in Kumamoto-Ken, Japan, on November 19th, 1890, Katsuma Mukaeda set off for the United States at the age of 18 to live with his uncle by marriage. From there, he enrolled in the University of Southern California, where he studied art, literature, and law. While he left off his studies in 1917, he would go on to complete his law education at what was then American Law School in Los Angeles twelve years later. Yet because only U.S. citizens could practice law in California, and as a Japanese immigrant ineligible for naturalization, Mukaeda was barred from practicing.

Instead, he would work a number of jobs that helped foster Japanese culture in the United States, including the distribution of Japanese films on the West Coast and promotion of Japanese cultural festivals. By 1935 he had already served as vice president of the Los Angeles Japanese Association and was head of the Southern California Central Association, a Japanese community group based in Los Angeles.

One lasting legacy from this period was his work with universities. In 1935, he helped established the Oriental Studies program at the Claremont Colleges (what was then Pomona College and Scripps College).He continued to serve at the Claremont Colleges as an advisor to the Japanese Department and Oriental Studies Department. It was here he developed a lifelong friendship with Pomona College’s fourth president James A. Blaisdell, who later praised Mukaeda as someone who could establish “just and honorable relations between the Japanese and Americans in this country.”1 Mukaeda’s continuous activism for the Japanese community made him a target for FBI surveillance in the months leading up to Pearl Harbor. On December 1st, 1941, J. Edgar Hoover drafted an order directing agents to arrest Mukaeda in the event of “a national emergency.”2

All of this came sadly true just six days afterwards. He later recalled in an interview that he was arrested on the night of December 7th, 1941, in the wake of the Pearl Harbor attack: “At about 11:00 PM, the FBI and other policemen came to my home. They asked me to come along with them, so I followed them…I arrived at the Los Angeles Police Station after 3:00 that night. I was thrown into jail there.”3 The next day, he was taken to the Lincoln City jail, and was soon transferred to the LA County jail. Ten days later, he was sent with 600 other suspects to Fort Missoula, Montana. Ultimately Mukaeda would suffer one of the longest recorded periods of confinement among wartime enemy aliens, remaining in official custody from the night of Pearl Harbor until February 11, 1946 - almost six months after the official surrender of Japan to the United States.

During this time, Mukaeda was held in four different camps across the United States. In each camp he experienced different hardships. At Fort Missoula, Montana, he was interrogated by FBI officials over anything that seemed to them remotely like evidence of loyalty to Japan. At Fort Sill, Oklahoma (recently the site of protest by Japanese-American activists over confinement of refugee children separated from their parents), he was handed over to the U.S. Army and “tagged with an I.D. number” like a prisoner of war.4 After a month, he was sent to another army camp at Camp Livingston, where he was housed alongside prisoners of war and Japanese internees taken from Latin America. Finally, Mukaeda was shipped to Santa Fe, New Mexico in 1943, where he remained until after war’s end.

In the course of this confinement, Mukaeda underwent at least three loyalty hearings, but each time the officials responsible blocked his release, despite a barrage of letters from family members, fellow activists, and business acquaintances, who repeatedly wrote the Federal government during this period to protest Mukaeda’s treatment and recommend his release.

In early 1942, after Mukaeda was taken into custody, the noted black attorney and activist Hugh Macbeth wrote multiple letters of support and signed an affidavit on behalf of Mukaeda. In the leadup to Mukaeda’s third hearing in 1944, Macbeth wrote the FBI that “in all of my thirty-two years of international activities of trying to bring about an understanding between all racial groups on this west coast of the United States, no one man has given better and more consistent cooperation than Mr. Mukaeda.”5

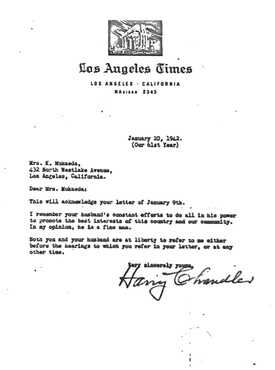

Even editor Harry Chandler of the Los Angeles Times, which was notorious for its anti-Japanese headlines, wrote Mukaeda’s wife Minoli in January 1942 to express his opinion that her husband had “promoted the best interests of our country and community” and promising to serve as a reference for hearings “or any other time.”6 In a 1975 interview with Buddhist priest and former internee Reverend Seytsu Takahashi, he continued to believe “they shouldn’t have interned a person like Mr. Mukaeda. He is a sensible man and worked hard for cultural exchange between America and Japan.”7 Yet more often than not, the official response to these letters was curt, stating only that they would be a part of Mukaeda’s file “for future reference.”

By 1944, following his third loyalty hearing, Mukaeda’s status in the United States remained precarious. After having answered yes to a form that asked if he wished to be repatriated if possible, he was marked for the rest of his time as untrustworthy. Although he sought to cancel his request multiple times, demonstrated good conduct, and even—ironically--taught courses to internees on American civics, he was denied a rehearing the next year.

After July 1945, his situation became increasingly dire following a proclamation by President Truman that all remaining internees were to be returned to their country of origin. After multiple pleas from Mukaeda’s wife and son, letters written from the President of Pomona College, a signed affidavit from Hugh MacBeth, and a letter from Professor Gordon Watkins of UCLA Mukaeda was able to provide substantial enough evidence for a final hearing. He was released on February 11, 1946.8

In the years following his return to Los Angeles, Mukaeda remained a staunch advocate of the rights of Japanese-Americans. He helped found a civil rights legal committee that lobbied for passage of the McCarren-Walter Act of 1952, which finally granted Japanese immigrants naturalization rights, and in May 1953 he and Gongoro Nakamura became the first two issei of Los Angeles to naturalize as U.S. citizens (an action for which he received a congratulatory letter from Mike Masaoka).

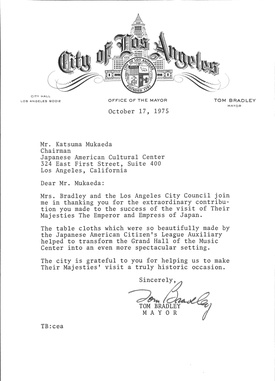

He likewise became a co-founder of the Japanese-American Community and Cultural Center in Los Angeles. Throughout the 1970s he received recognition from Los Angeles Mayors Sam Yorty and Tom Bradley for his community work, and on a national level was appointed as an adviser to the White House Conference on Aging in 1970.9 Perhaps the height of the honors conferred on Mukaeda came in 1970, when he was awarded the Order of the Sacred Treasure Third Class by the Emperor of Japan.

Mukaeda was like many issei - he was an immigrant who came to the United States with a hope for a new life, but was forced to struggle for equal rights. Despite the prejudice and hardships he faced, he continued to firmly believe in the promise of America. As he put it, “I trusted the American people, even though they did not give me American citizenship.”10

Mukaeda’s resolve, and his later success, do not exonerate the United States for its unjust treatment of him, nor should his courage absolve us as Americans of any responsibility for the government’s actions. Although in the end he narrowly escaped deportation, his long wartime confinement offers a lesson in the psychology of confinement: even as Mukaeda strove during the prewar era to improve relations between Japanese-Americans and the larger community, officials misread these good deeds a evidence of pro-Japanese sentiments.

Mukaeda’s story also helps reminds us of the bitter legacy of Fort Sill and the camps. Today, the existence of ICE and the structure of the current immigration system should likewise stand out as a point of shame—if migrants to the United States are forced to endure new hardships by USCIC, we should not be surprised if some of them lose hope. We are fortunate to have people courageously protest and remind the government that such places should never be resurrected.

Notes:

1. Letter from James A. Blaisdell to Willard F. Kelly, National Archives RG 60, Mukaeda File.

2. Order from J. Edgar Hoover, National Archives RG 60, Mukaeda File.

3. Interview with Katsuma Mukaeda, 1975. From Japanese-American World War II Evacuation Oral History Project Vol. 1: Internees, (Westport: Meckler, 1991), 7.

4. Interview with Katsuma Mukaeda, 1975. From Japanese-American World War II Evacuation Oral History Project Vol. 1: Internees, (Westport: Meckler, 1991), 9.

5. Letter from Hugh Macbeth to Willard Kelly, Immigration and Naturalization Services. National Archives RG 60, Mukaeda File.

6. Letter from Harry Chandler to Minoli Mukaeda, National Archives RG 60, Mukaeda File.

7. Report on Katsuma Mukaeda, Immigration and Naturalization Services. National Archives RG 60, Mukaeda File.

8. Letter from Mayor Tom Bradley to Katsuma Mukaeda, October 17, 1975. Japanese American National Museum Archivem Mukaeda papers.

9. Interview with Katsuma Mukaeda, 1975. From Japanese-American World War II Evacuation Oral History Project Vol. 1: Internees, (Westport: Meckler, 1991), 10.

© 2019 Jonathan van Harmelen