Naka and Pearl Nakane and Chicago

FBI #65-562-140.

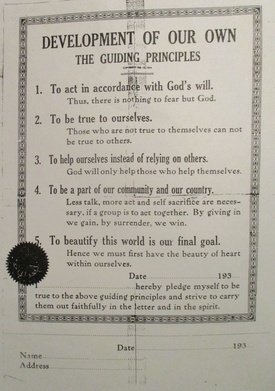

Did Naka Nakane ever come to Chicago? How much political influence did he have in Illinois? Did the Japanese consulate in Chicago somehow get involved in Nakane’s “black maneuver” in the Midwest? All that can be said at this point is that two documents purporting to be pledges from the Development of Our Own were found among others in a search of the former Japanese consulate in Chicago.1

The Development of Our Own was incorporated as a non-profit organization in Illinois on October 1, 1936. Its address was listed in Springfield, IL, and, according to an FBI report, its object was “to develop for the members a higher human standard without infringing upon the rights of others, namely; morally, socially and intellectually to enjoy a just life.” The report further observed that “A very large woman resembling an Indian” was involved in the incorporation, but the organization in Illinois later dissolved on October 27, 1939 for failure to file the required annual reports with the Secretary of the State.2 Pearl Nakane later admitted that Nakane “had made her national organizer for The Development of Our Own in 1934 and that in this capacity she had traveled to Springfield, IL, where a charter for this organization was obtained from the Secretary of State of Illinois and a unit established. She went to Rockford too, but no unit was organized.”3

On the other hand, the Onward Movement of America was never incorporated in Illinois.4 In an article titled “Development of Our Own” published in Detroit’s black newspaper, the Tribune Independent, on April 21, 1934, Nakane referred to a Japanese woman living in Chicago as his collaborator: “Permit me to say to you men, that our international supervisor is a woman, if you please, with whom some of the members of the board of control have already had an interview. She is now in Chicago and is doing wonderful work among the white people, though different from my work. If I say this, you may wonder what a Japanese woman can do among the white people, in relation to the freedom and independence of the colored race. I am telling you she can and has demonstrated herself capable of performing her mission, which is to create a new tendency among the white race, for racial equality. That is, to convince them of the fact that they have been creating many enemies for many years, not in the foreign land, but right here in this country’s national boundary.”

The FBI investigation revealed that the name of the Japanese woman in Chicago, suspected to be Nakane’s collaborator, was Fay Watanabe. She was a tourist agent in Chicago who handled all Japanese transients entering the city.5 Pearl Nakane already seemed to know Watanabe in December 1933. At a meeting of The Development of Our Own on December 8, 1933, Pearl Nakane announced that she had just returned from Chicago where she had had an interview with the Chicago Japanese consul and that he had assured her that there was no need for alarm. Then she solicited donations to secure Nakane’s bail.6

Following the trip, she wrote the following note to her husband, who was imprisoned in Wayne County Jail in Detroit: “I am just back from Chicago. Mr. Yoshio Muto, also Mrs. Watanabe sends love to you. I shall not desert you. I am sending $1 also some cigarettes.”7 Consul Yoshio Muto‘s term of office in Chicago was from May 1931 until April 1934. It was not impossible for Pearl to have met him.

Was there a Japanese woman who was a tourist guide in Chicago? Yes, there was. In May 1931, Sadako and Fujiko Watanabe opened the Chicago Nippon Club at 19 East Goethe St in Chicago. Their business was to provide lodging, Japanese food, and tour guides, and arrange boat and train tickets, shopping and interpreting for Japanese tourists. It was also a social club for members. According to an advertisement in a Japanese newspaper, the club was located in quiet area, within ten minutes of the Japanese Consulate, business areas and train stations, one block from Lake Michigan and three blocks from Lincoln Park, and that the big clean rooms had bathtubs and were perfect for families.8 In April 1932, the Club changed its name to “The Tokiwa” and the owner listed was only Fujiko Watanabe.9

Although her English name did not appear in an advertisement of “The Tokiwa” in a Japanese newspaper, a report titled “survey of Nisei of Chicago” made by M Ishide on April 10, 1941 listed Faye Watanabe as a tourist guide. Camp records as well listed a Faye Fuji Watanabe, who arrived at Manzanar camp on June 1 1942 and departed the camp for New York on February 16 1943.10

With this information in mind and that Tokiwa’s telephone number (Superior 0536) was very similar to the one that the FBI investigated, (Superior 0566)11, Fujiko Watanabe of the Tokiwa might very well have been Faye Fuji Watanabe, tourist guide . She was a Nisei, born in Washington in 1909, and listed in 1930 Chicago census as a 21-year-old waitress working at the railway station restaurant under name of Funi Faye Watanabe. She lived and worked with another Nisei from Washington, 22-year-old Ruth Horn Sakura, and Kiwa Uchimura, a 30-year-old single woman from Japan.12

According to the FBI, Pearl had found “Miss Watanabe’s name either in a magazine or among her husband’s papers.” “While in Chicago she contacted Fay Watanabe, who stated to her that she did not know [Naka] Nakane and accordingly would be unable to help him out.“13 Other members of the organization, besides Pearl, had also correspondence with Fay Watanabe, although her address was care of Cedar Hotel at 1118 North State St,14 not at The Tokiwa.15

Taking into consideration that it was generally known among African Americans that they could write to the Japanese consul in Chicago for literature on Japan and that Pearl Nakane herself obtained politically innocent booklets such as “Japan – China, a Pictorial Primer” and “America and Japan’s Manifest Destiny” from the Japanese consulate in Chicago,” it was possible that they were also furnished with the name of Fay Watanabe for the same purpose. At the same time, due to her travel business, Fay/Fujiko Watanabe was at risk of suspicion for being a contact for Japanese espionage agents operating in this country.16

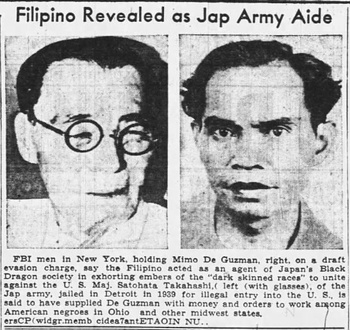

Was there any chance that Naka Nakane met Fujiko Watanabe in Chicago? It might have been possible, as the timing was right. Nakane came to Chicago in the spring of 1932 before settling in Detroit, and attended at a Chicago meeting of the Universal Negro Improvement Association.17 After the meeting, Nakane approached De Guzman, a Filipino, and his Chinese partner, and to them “indicated his intentions to found a pro-Japan organization.” Three months later, the three organized a group for African Americans in Chicago, the Pacific Movement of the Eastern World “and transported (it) to St. Louis, (Missouri) in that same year.18 From there the group extended its network to” other areas in the Midwest such as Kansas, Missouri, Southern Illinois, and Oklahoma.19

Nakane’s organizing activities in Chicago left two other Japanese names in history, besides Fay Watanabe. One was Harry Ito, head of the Chicago chapter of The Development of Our Own20 and the second was Isamu Tashiro, a dentist who had attended a meeting of Onward Movement of America in Detroit in 1937.

A Harry Ito was listed in the 1940 Chicago census, but the Ito in the census was 36 years old and engaged in the grocery store business. It is doubtful that the Ito in the census was involved in the agitation of African Americans with Nakane. Furthermore, the Chicago FBI, in investigating the African American community in Chicago regarding the existence of a branch of The Development of Our Own, did not find any evidence.21

Isamu Tashiro was born in Hilo, Hawaii in August 1895 and came to Chicago around 1911, when he was 16. He graduated from the Chicago College of Dental Surgery in 1918.22 When he was a dental student in 1918, he played in the semi-professional All Nation Baseball club, run by the Chicago Exhibition Company. Featured in the club were four African Americans and two Native Americans, several white players, and Tashiro.23 Playing in such a racially mixed team, Tashiro must have been open-minded, to some extent, regarding race relations.

Being a Christian who was thankful that he, “with God’s help, can make (himself) useful to my fellow American friends,”24 he gave a lecture sponsored by the Race Amity Committee of the Chicago Baha’I fellowship, at the Baha’I assembly in Chicago in November 1936. The theme of his lecture was “The Human Side of Japanese Life.”25

With such an obvious interest in multicultural education and Christian beliefs, it might have been natural for Tashiro to agree innocently to the Development of Our Own's request to attend their meeting in Detroit in fall 1937. Tashiro reported to the FBI that “the invitation was extended by Mrs. Takahashi (aka Pearl Nakane) and that the organization paid his transportation expenses … and offered him an honorarium which he declined.” According to Tashiro, the “dinner was held in a hall … and a picture of Major Takahashi (aka Naka Nakane) wearing a long black beard was on display during the dinner.” “Mrs. Takahashi boasted of having charters for that organization in numerous states and a total of 30,000 members.” At the meeting at which “there were between 500 and 800 people present,” Tashiro gave a talk on the “four seasons of Japan,” showing “motion pictures which he had taken in Japan as a part of his lecture.”26

After that occasion, Pearl Nakane and other members contacted Tashiro several times to “request that he arrange an audience with the Japanese Consul.”27 Although he was also the subject of the FBI case entitled “[redacted].. Registration Act-J” and he had direct contact with the members of the Development of Our Own, the reason that he was not arrested may be due to the fact that “on several occasions he has appeared in the Chicago office (of the FBI) to furnish information on Japanese activities and in most instances his information has been found to be reliable.” On the other hand, the FBI received “numerous complaints to this office questioning his loyalty to the United States.”28 After Nakane was picked up in June 1939, Pearl both wrote and went personally to Chicago in an effort to enlist aid, but her effort was not productive29 although she set up a mailbox in the Chicago Post office for her husband.30

Nakane had applied several times to repatriate to Japan on the first exchange ship leaving in June 1942, but his applications were denied and he remained in detention at various camp hospitals in Wisconsin, Louisiana, New Mexico, California, Kentucky, and Texas until he was paroled in September 1946. In November 1945 he declared to officials that “he was previously anti-American in his war views because he did not know the American intention. He has lately come to hope for U.S. victory, however, as he claims to have a better understanding of the policies of this country. He contemplates the cancellation of his petition for repatriation and would like to remain in this country if allowed to do so.”31

In early 1946, the Justice Department alien enemy internment camp in Santa Fe, New Mexico was a focal point for suspicious Japanese in the Midwest: both Eizo Yanagi and Naka Nakane were detained there. But at the camp there was another suspicious character, a Japanese man who had once worked in Chicago named Asataro Yamaguchi.32

Yamaguchi was interned in Santa Fe because he was “quoted as saying to the negro proprietor and his assistant in Cincinnati that the colored people of the world have been oppressed so long by the white people that the colored people ought to get together and wipe them out,” and that “in Japan colored people would be treated better and that Japan would ultimately win the war.” Because of this statement, The Hearing Board in Cincinnati regarded him as a real danger and accordingly, unanimously recommended the internment of Asataro Yamaguchi.33 Yamaguchi’s statements indicate how much the idea of Japanese leadership in the worldwide fight against racism had spread among private citizens, not only in Japan, but also in the U.S. But how much had this idea taken hold in the African American community?

In June 1943, the American Institute of Public Opinion conducted a nation-wide survey on the question, “which country do you think we can get along with better after the war -- Germany or Japan” and an interesting result came to light. Overall, 67 percent of the voters voted for Germany, while only 8 percent voted for Japan. But a comparison of voters by race showed a clear difference: while 70 percent of white voters were for Germany and only 7 percent for Japan, among African American voters, 30 percent were for Germany and 22 percent for Japan. These results show how effective Japanese propaganda was, not only in the Midwest, but in the general population of the African American community in the country.34

All in all, Chicago was not the primary location for Japan’s organizing schemes among African Americans. Through official channels (the Japanese consulates), they planned to work in Chicago “after Mr. Hikida’s work in New York while at the same time working assiduously in Washington.”35 However, we cannot ignore the work of individuals such as Naka Nakane, who had the audacity to engage in a complicated game of racial world power.

Notes:

1. FBI memorandum for Mr. F.L.Welch, dated September 16, 1943, FBI #65-562-140.

2. FBI Report Springfield, IL, dated January 13, 1943, FBI #65-562-122.

3. FBI Report Detroit, dated March 20, 1940, FBI #62-709.

4. FBI Report Springfield, IL, dated April 3, 1940. FBI #65-562-49.

5. FBI Report Detroit, dated March 20, 1940, FBI #62-709.

6. Ibid.

7. Ibid.

8. Nichibei Jiho, May 13, 1931.

9. Nichibei Jiho, April 27, 1932.

10. Rosters of Evacuees at Relocation Centers 1942-1946, ancestry.com.

11. FBI Report Chicago, dated May 10, 1943, FBI #65-562-130.

12. 1930 Census.

13. FBI Report Detroit, dated March 20, 1940, FBI #62-709.

14. Chicago City Directory 1928-1929.

15. FBI Report Detroit, dated March 20, 1940, FBI #62-709.

16. Ibid.

17. Ernest Allen, Jr, "When Japan Was 'Champion of the Darker Races:' Satokata Takahashi and the Flowering of Black Messianic nationalism", The Black Scholar, Volume 24, No. 1, page 31.

18. Ibid, page 37.

19. Ibid, page 26.

20. Ibid, page 38.

21. FBI Report Chicago, dated May 10, 1943, FBI #65-562-130.

22. Chicago Tribune, Dec 21, 1983.

23. Gary Ashwill, "Isamu Tashiro, 1918. Chicago All Nations," Agate Type, October 2013.

24. Tashiro letter to Carey McWilliams, dated December 7, 1942, Carey McWilliams Collection, Claremont College, Asia and the America, March 1943.

25. Chicago Tribune, October 28, 1936, Chicago Defender, October 31, 1936.

26. FBI Memorandum, dated April 11, 1944 from SAC to Hoover, FBI #65-562-152.

27. Ibid.

28. Ibid.

29. FBI Report Detroit, dated March 20, 1940, FBI #62-709.

30. Nakane file, WWII Alien Enemy Internment Case Files, 1941-1954, General Records of the Department of Justice, RG 60, Case File 146-13-2-43-18, Box355.

31. Ibid.

32. Ito, Kazuo, Shikago Nikkei Hyakunen-shi, page 323.

33. Asataro Yamaguchi File, WWII Alien Enemy Internment Case Files, 1941-1954, General Records of the Department of Justice, RG 60, Case File 146-13-2-58-176, Box541.

34. Los Angeles Times June 11, 1943.

35. Telegram from Ambassador Nomura to Tokyo, dated July 4, 1941, The “Magic” Background of Pearl Harbor, Volume II Appendix, page A-180.

© 2019 Takako Day