Background

Pre-World War II Chicago had no segregated residential enclaves for Japanese residents like the Japantowns and Little Tokyos on the West Coast, but this did not mean there wasn't a Japanese community. Actually, there was a Japanese community, but it was more of an invisible mental space in the Japanese residents’ minds than a physical community.

Although Japanesehad livedscattered throughout Chicago since the 19th century, they certainly had formed various community groups and organizations. Becoming members of those groups and attending their meetings helped these people maintain their identity as Japanese. In fact, a sense of community was needed by the Japanese immigrants, because “even in such a cosmopolitan city as Chicago, where, because of the comparatively small number of Japanese, prejudice against them was at a minimum, the Japanese residents…were made to feel that they were not an integral part of the social life of the city. They were not welcomed to the social functions of Americans who were their equals in income and business position.”1 As such, they needed a sense of belonging, so forming groups with their fellow countrymen who shared the same language and culture was a natural survival strategy and it continues for Shin Issei even today.

The first Japanese group, called "The Japanese Club", was formed in Chicago in 1892 with about twenty Japanese residents, to prepare for the 1893 Columbian Exhibition. Dr. Masuo Ikuta, assistant in the Chemistry Department at the University of Chicago2 was chosen as president, George Sasaki, a student of literature and Christianity, was chosen as secretary, and K. Nakayama, who would later to open the gift store “The Nippon” at 48 Adams between State and Wabash Streets for the Exhibition, was chosen as treasurer.3

Over the next 50 years, many groups and organizations were formed for the mutual benefit and welfare of Japanese Chicagoans, and some of them had a close relationship with the Japanese Consulate of Chicago, which was established in December 1897.

Japanese Christians formed the Japanese YMCA (Young Men's Christian Association) in 1908, the Japanese Mutual Aid Society of Chicago was established in 1910 under the guidance of the Japanese Consulate, and various Japanese business groups sprouted in the 1910s and 1920s, although many were short-lived. The Japanese Society of Chicago was formed in 1927 and a subcommittee helped with the Japan exhibit at the 1933 Chicago Fair, "A Century of Progress." The Chicago Business Club started in 1934, and finally, a new Japanese Mutual Aid Society was formed in 1935. All of these groups were interconnected, as their membership rosters overlapped over the years.

Immediately after the Pearl Harbor attack in December 1941, the only surviving organization, the Japanese Mutual Aid Society, was ordered to cease all activities, not to collect dues, and not to congregate in groups of any more than three persons.4 In addition, the houses of several members of the Society, including Hidefumi Mukoyama and Masuto Kono, were searched by the FBI.5 However, actual arrests were made to only to three key members who were deeply involved with the Japanese Mutual Aid Society from the beginning: Charles Yasuma Yamazaki, president, Masuto Kono, one of the board members, and Shoji Osato, an agent of the Japan Travel Bureau, a subsidiary of the Japanese government.

Although their arrests could be seen as a natural consequence of the government’s suspicious eyes on organizations with strong ties to Japan through the Japanese consulate (similar to what happened on the West Coast), what is peculiar about the Chicago Japanese was that they were arrested not once, but twice: in 1941 and 1943. Osato was arrested in December 1941, and Yamazaki and Kono were arrested in December 1943, after Osato was paroled in May 1943.

The difference in the timing of the arrests of these Chicago Japanese was possibly a result of their contact with the African American community, as seen in case of Eizo Yanagi, who was arrested twice and transferred every year from 1942-1946 to camps and detention centers under the Department of Justice. Did the Japanese Mutual Aid Society have suspicious contacts with African Americans in Chicago? If so, what kinds of contacts were made, and how were Yamazaki and Kono involved in those contacts? We must also remember that in 1943, race riots also occurred in June in Detroit, Michigan.

The Japanese Mutual Aid Society

The Japanese Mutual Aid Society was formed in January 1935, with Kenji Nakauchi, the Japanese consul, as honorary president. The Society had three main purposes: 1) to purchase centrally located cemetery lots; 2) to help pay final expenses of anyone who died without family or funds; and 3) to provide any necessary social services to the Japanese community in Chicago.6 The first office was located at 816 North Clark Street;6 these premises were occupied by a restaurant owned by Frank Yasunori Maruyama, treasurer of the Society. This restaurant had once been known as “Chicago Lunch,” owned by Charles Yasuma Yamazaki.7 Yamazaki subsequently sold it to Maruyama in 1930, who was an employee at the restaurant.8

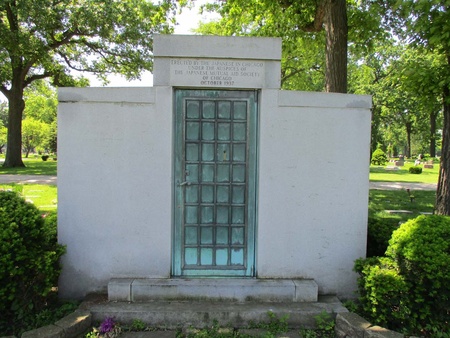

The Japanese Mutual Aid Society started out with more than 100 members, and the membership fee was 50 cents.9 Their first act was to start a fund drive for a Japanese cemetery; the Society purchased a lot at Montrose Cemetery in March 1935, completed the mausoleum, and had an unveiling ceremony on Memorial Day in 1938.10 With several Hawaiian-born Nisei members, including Isamu Tashiro, a dentist, and Paul Yoshio Kirimura, a pearl salesman,11 the Society incorporated under the laws of the State of Illinois in 1939.12

The society’s funds were left in the trust of the Japanese Consulate, and the signature of the consulate secretary was requiredat the time of any withdrawals, in order to protect the members of the Society.13 Accordingly, the Society maintained close working relations with the Japanese Consulate during the ensuing years.14

In fact, the Consulate became more politically influential over the Chicago Japanese and their associated groups after the Mukden incident in September 1931. The Japanese Society of Chicago started a fundraising drive to provide relief supply bags to Japanese soldiers in Manchuria, collected $669.62 with cooperation of various Japanese groups and sent it to the Japanese Army through the Consulate.15

After the Second Sino-Japanese War broke out in July 1937, activities of the Japanese Mutual Aid Society were more inclined to shadow the patriotism and nationalism seen during these times in Japan. The Society organized an emergency committee in August 1937 to help with home front responsibility from overseas. The committee had 25 members, including Yamazaki, Kono, Osato and Consul Masutani.16 According to Mayumi Hoshino,“While some Japanese Chicagoans seemed to unconditionally support their native land, some did not, disagreeing with much being done by the Japanese government, especially its military operations in Asia.” 17 For example, it was reported to the consulate that a book titled Resistance and Founding of a State, a collection of lectures by Chiang Kai-shek and a pamphlet titled King (a collection of anti-war short essays, both of which were written in Japanese) were circulating among Japanese in Chicago.18 However, according to Hoshino, “Overall, the organization enthusiastically promoted strong external ties with the motherland and internal ties within the Japanese community of Chicago.”19

What follows are just a few examples of fundraising drives by the committee: $964.25 in total from nearly 200 Japanese residents to send “relief funds” for Japanese soldiers in China in September 1937,20 $597.50 for an Asahi newspaper company campaign to help the Japanese government purchase a military aircraft in October 1937,21 and donations for Japanese soldiers’ families in October 1938.22 In October 1939, Yamazaki, a life member of the Japanese Red Cross, announced a drive to recruit new members for the Japanese Red Cross, and more than sixty Japanese joined the organization.23

Japanese women also participated in patriotic fundraising drives. In February 1938, the Japanese Women’s Club of Chicago, a Japanese language school, and a Japanese Christian Church all housed at 214 W. Oak St., started a drive to make and send “relief supply bags” to Japanese soldiers in China. With the money they collected, they made 350 bags and sent them to Japan.24 The bags were filled with necessities such as bath tissues, towels, soap, clothes, food, medications, photos, pictures and security blankets for fighting soldiers.25

In February 1940, another “relief supply bag” drive took place with the sponsorship of the Women’s Club and support of the Japanese Mutual Aid Society.26 With Mrs. Ashino, wife of Consul General Ashino chairing the campaign,27 the Japanese wives of the Club and the Society collected $438.28, from which 539 bags were made. Other individuals made an additional 225 bags, and in total, 764 bags were sent to Japan through the Japanese Consulate.28 In return, a personal letter of appreciation, written by a soldier in South China and addressed to the Japanese Women’s Club and the Japanese Mutual Aid Society, was received in September 1940.29

During the war, the Society also returned to one of their original purposes: to provide social services to the Japanese community in Chicago. Although they were forced to stop all regular activities, in June 1943, the Japanese Mutual Aid Society was able to organize the Mutual Service Center at 537 North Wells Street, a hostel for Japanese and Japanese Americans who were resettling in the Midwest from the various American concentration camps.30 Elmer Sherrill, Midwest Director of the War Relocation Authority, gave his hearty approval of the Society’s efforts31 and the Police Department made no objection to the project.32 According to Yamazaki, the Society made a donation of $200, Frank Maruyama made a loan of $300 and Frank Fukuda, owner of a restaurant on North Clark Street, also made a loan of $350 to get the Center up and running.33

Although there were no actual officers at the Center, its policies and decisions were made by a committee consisting of Yamazaki, Kono, Mukoyama, Maruyama and Fukuda. A Japanese couple, Togawa and his wife, were the actual managers of the Center.34 The center had approximately thirty rooms and other accommodations for twenty more people. Sliding scale rates were charged in accordance with the person’s ability to pay. Most of the hostellers stayed for a short period of time before finding permanent quarters and no profit was realized in the operation of the hostel.35 Despite the Japanese Mutual Aid Society's“pro-Japan” activities between 1937 and 1941, and the good-willed hostel program in summer 1943, Charles Yasuma Yamazaki was arrested on December 3, 1943.

Notes

1. Steiner, Jesse F, The Japanese Invasion: A Study in the Psychology of inter-Racial Contacts, Dissertation, University of Chicago, 1917, page 109.

2. Annual Register, 1892-1893, University of Chicago.

3.Chicago Tribune, Dec 11, 1892.

4. Bulletin of the Japanese Mutual Aid of Chicago 1934-1977, page 3, JASC Legacy Center Collection.

5. Ito, Shikago ni Moyu, page 215.

6. Bulletin of Japanese Mutual Aid of Chicago 1934-1977, page 2, JASC Legacy Center Collection.

7. 1923 Chicago City Directory.

8. Charles Yasuma Yamazaki file, WW II Alien Enemy Internment Case Files, 1941-1954, General Records of the Department of Justice, RG 60 Box 266, Case File # 100-7471, National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, Maryland.

9. Nichibei Jiho, February 9, 1935.

10. Bulletin of the Japanese Mutual Aid of Chicago 1934-1977, page 3, JASC Legacy Center Collection.

11. 1940 Census.

12. Nichibei Jiho, January 28,1939.

13. Nichibei Jiho, February 9, 1935; Yamazaki FBI File No 100-7471, RG 60, Box 266.

14. Bulletin of the Japanese Mutual Aid of Chicago 1934-1977, page 2, JASC Legacy Center Collection.

15. Nichibei Jiho, May 14, 1932.

16. Nichibei Jiho, October 2, 1937.

17. Hoshino, Mayumi, Strangers in the Heartland: Cultural Identity in Flux, Japanese Americans in Chicago, 1892-1942, Dissertation, Indiana University, 2012, page 244.

18. Report from Consul Ashino in Chicago to Nomura, January 12, 1940, Diplomatic Archives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, A-1-1-0-30_2_4_001.

19. Hoshino, page 235.

20. Nichibei Jiho, September 4 and October 2, 1937.

21.Nichibei Jiho, November 6, 1937.

22. Nichibei Jiho, November 5, 1938.

23. Nichibei Jiho, November 11, 1939.

24. Nichibei Jiho, April 16, 1938.

25. Nichibei Jiho, February 10, 1939.

26. Nichibei Jiho, February 10, 1940.

27. Nichibei Jiho, February 24, 1940.

28. Nichibei Jiho, March 30, 1940.

29. Nichibei Jiho, September 7, 1940.

30. Bulletin of the Japanese Mutual Aid of Chicago 1934-1977, page 3, JASC Legacy Center Collection.

31. Yamazaki FBI file No100-7471, RG 60, Box 266.

32. Bulletin of the Japanese Mutual Aid of Chicago 1934-1977, page 3, JASC Legacy Center Collection.

33. Yamazaki FBI File No 100-7471, RG 60, Box 266.

34. ibid.

35. ibid.

© 2019 Takako Day