Yamauchi returned to the world of the Depression-era desert in The Music Lessons, which premiered in 1980 at the New York Public Theater. The play, based like Soul on one of Yamauchi’s short stories (In Heaven and Earth), is a Tennessee Williams-esque tale of an itinerant laborer in his 30s named Kaoru who comes to a widow’s farm looking for work. The widow, Mrs. Sakata, has three children: two sons and a daughter, Aki. The rootless Kaoru begins giving violin lessons to the 15-year-old Aki, who, innocent and isolated, falls in love with him. One night, when Mrs. Sakata goes out to the shed where Kaoru is living, wondering why she no longer hears the strains of his violin, she catches the man and her daughter together in a moment of intimacy, initiated by the girl herself. Nothing untoward has actually occurred, but the widow is beside herself, and banishes Kaoru from the farm, only to have Aki threaten to run away with him. Her mother says:

“You know what you’re asking for? From town to town… no roots… no home… nothing. Maybe one day, he’ll get tired of you… throw you out… leave you in some dirty hotel for another fool woman. Think, Aki. And you’ll come crawling home…”

Aki is not dissuaded, but in the end, although Mrs. Sakata is resigned to giving up her daughter, Kaoru refuses to take her with him, and the broken-hearted girl remains at home. Critics found this drama about a seductive drifter somewhat derivative, but Yamauchi never saw a need to be inventive for its own sake, and it was clear, in the character of Mrs. Sakata, and the conflict between her and Aki, that the playwright had returned to her pervasive themes: just as with Mrs. Murata in Soul, Mrs. Sakata has sublimated her emotional self in order to survive, and believes nothing good can come of her daughter indulging romantic notions about love and life that would only lead to heartbreak, if not worse.

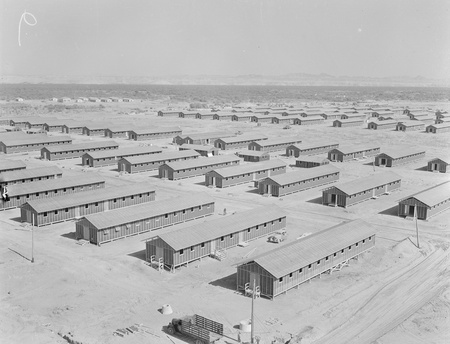

Perhaps the most important of Yamauchi’s plays after Soul is 12-1-A, her attempt to explore the full breadth of her camp experience on stage. The play is named after the block, barrack, and unit she and her family were assigned to in Poston. In 12-1-A, she successfully captures the everyday reality of camp life; of people, unsure of their ultimate fate, doing their best to soldier on, when their own country (at least in the case of the Nisei) has locked them up and turned its back on them. The Tanaka family is at the mercy of the elements, like the dust storm that strikes the day they arrive, and of the U.S. government, which provides the basic necessities of life while at the same time depriving the internees of their rights as citizens, their self-determination and, to a great degree, their dignity (though their will to endure helps restore it).

“We lived one family to a unit, four units to a barrack with knotty walls separating us from our neighbors. There was little privacy. Furtive love affairs were conducted in the shadows of barracks and in empty office rooms. Family quarrels were stifled and swallowed. The latrines were the worst: rows of toilets back to back, one long trough for washing, a shower room with six shower heads. The modest met each other coming and going in the rare hours of the morning.

We waited in line everywhere: at the mess hall with our tin plates, at the post office, the clinic, the showers, at the canteen, in the blazing sun and cold rain. It got so that wherever a crowd gathered, people automatically got in line.” (American Dream)

Only towards the end of the war are they given a say in their destiny, but the choice, at least for young men of draft age, is bitter: fight—and perhaps die—for the country that betrayed you, or suffer the fate of a traitor.

This choice is at the heart of the play’s main conflict, centering around two young friends, Mitch and Ken, arguing over how to respond to the loyalty oath. Mitch is unable to forgive, unlike Ken who is eager to prove himself a worthy and loyal American. For those Japanese Americans who fought the Nazis as members of the Army’s 442nd Infantry Regiment (the most decorated unit of its size in U.S. military history) and survived, their service was a source of inexhaustible pride; for those who went to Tule Lake or Fort Lincoln, there was no such glory, only a sense of having stood on principle, the rewards for which were slow in coming, if they ever arrived at all.

Yamauchi, too, adhered to her principles, even if it meant not finding as wide an audience as she might have otherwise. In a UC Berkeley correspondence course she took after the war, her instructor criticized a story she turned in (The Sensei) as painting too dark a picture of life for those older Japanese who never quite recovered from internment. Yamauchi refused to lighten the tone of her piece, and instead resolved to forgo writing for the mainstream white culture; she would focus on those who knew what she had experienced, and believed what she believed, that the racism unleashed against Japanese Americans in the 1940s was an extension of the past and a harbinger of the future. It would be unfair to expect anyone who had once been imprisoned based on their race to believe otherwise.

She did attempt to reach a broader demographic in two of her plays, Stereoscope (1988 [a one-act that later morphed into a two-act entitled Taj Mahal]) and The Chairman’s Wife (1990). The former was a bold effort to dramatize the life of a middle-aged white vagrant named Harold who unburdens himself to 19-year-old all-American boy John in a Tucson freight yard in 1929. As they take a break from riding the rails, Harold reminisces about a girl he fell for and the stereoscope, an early 3-D viewer, that he stole from her—his window into a world of exotic, faraway places and erotic fantasies:

“Well, I be workin’ on this here ranch—’s lil’ while back—an’ the boss—ferget his name now—he done bought his darlin’ daughter this stereoscope an’ some pitchurs fer it. Cain’t use no ord’nary pitchurs, y’ know…these gotta be two on a card, leetle bit differnt fum each other and yer look through this here gadget an’ one eye see one pitchur an’ th’ other eye look at th’other pitchur and wooh! Sunn’ly this here piece a cardboard take on a life a its own….You can almos’ walk inter a palace a shiny marble floors wi’ the sun comin’ through them winders, an’ stachoos all lined up the halls, and ever’thin’. Taj Mahal. Ever hear a that? She liked to look at that’un, the girl. She sez, ‘I’ll show yer the Taj Mahal, Hal.’ She loved that pitchur.”

When the play, at the behest of an East West director named Rodney Kageyama, evolved into Taj Mahal, Harold became a black man named Jake and John an undocumented Japanese immigrant named Jun who is trying to stay one step ahead of the authorities. When Jun’s wallet is stolen by a thief, he crosses paths with Jake, two lost souls pursuing their unattainable dreams.

The Chairman’s Wife features Mao Zedong’s widow and one-time actress Jiang Qing—Madame Mao—who, as a member of China’s “Gang of Four,” was a principal force behind the Cultural Revolution of 1966-76. Falling from grace after her husband’s death, she escaped execution but was sentenced to life in prison. Yamauchi envisions Jiang Qing in her cell, reliving the vicissitudes of her life as the events leading to the Tiananmen Square Massacre unfold in the streets outside. Yamauchi opted not to have her subject directly address the audience; instead, she reveals her character through her interactions with other figures onstage. By attempting to get inside Jiang Qing and understand her motives and justifications, Yamauchi hoped that the audience would come to understand and even empathize with a ruthless woman whose legacy as an architect of the Cultural Revolution is now seen as having brought death and suffering to millions. A year after Yamauchi’s play premiered, its real-life protagonist, after being released from prison and dying of cancer, hanged herself in a hospital bathroom.

Two more plays in Yamauchi’s oeuvre merit mention: The Memento (1984) and Not a Through Street (1991). The latter is a minor work that again, was loosely based on a short story: “A Veteran of Foreign Wars.” In the story, a Nisei divorcee interacts with a one-legged veteran of the second battle of Corregidor (“oh, no!—fighting against our own”) who lives down the block. In the play, the Nisei woman is a neurotic busybody, still married but with grown children who never visit, and Yamauchi adds a third character, a second woman who has mysteriously withdrawn from life.

The Memento, originally The Face Box, was first produced in 1984 by Tisa Chiang in New York, and three years later by Lloyd Richards at Yale Repertory. The play opens with two middle-aged women in California as they rekindle an old rivalry over a man, recently deceased, whom they both loved and one of them married. The spurned woman, who remained a spinster, owns an antique Japanese mask that, whenever she places it over her face, mysteriously transports her back in time to ancient Japan, where she becomes a geisha married to a mask maker. The lives of the two women, past and present, have poignant and bitter similarities, with the seductive, sinister spirit of the geisha threatening to engulf the present-day woman in madness.

© 2019 Ross Levine