1. Atomic Bomb Survivors in the Americas

What comes to mind when you see or hear the phrase “survivors of the bomb in North and South America”? What images, stories, and emotions do these words bring? For some, the words “bomb in America” might suggest the drug war in Mexico or the terrorist attacks in the United States. Those who immediately equate the term “the bomb” with the nuclear destruction in Hiroshima and Nagasaki might feel equally puzzled by the phrase because these cities are not in the Americas. To many

of us, these Japanese cities, which suffered the first nuclear annihilation in the history of mankind in U.S. attacks, ought to be set in opposition to America, not placed within it.

The purpose of this book is to eliminate this seemingly unbridgeable distance between the ruined cities and the country that made and used the weapons against them—and to challenge the prevailing view that the only survivors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki are the Japanese. We want readers to see Hiroshima and Nagasaki as being beyond the Pacific Ocean, not circumscribed or separated by it. We hope they become more immediate, more real, as their influence extends across the ocean. We hope that the stories and images in this book will bring readers to think about the impact of nuclear disaster, regardless of where it happens, and its consequences regardless of the nationality and residency of the people whose lives are affected by the catastrophe.

2. Going Beyond the Ocean

The people encountered in this book show that the bomb can happen to anyone and everyone, regardless of national belonging, cultural background, family history, religious belief, or political inclination. The common experience of survivors—something so terrifying that it is nearly incomprehensible to the rest of us—is lived by people in different cities and villages in numerous countries.

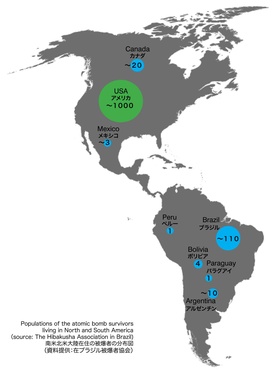

Survivors are among us, are one of us, no matter who we are. It is our hope that these survivors’ stories bring the bomb closer to us in a meaningful way. As the statistics on this page show, the number of survivors living in North or South America is not large compared to their counterparts in Japan, but it is substantial. Our best estimate as of this writing is that there are a few more than one thousand survivors living in North America, including those in Canada, the United States, and Mexico. As for South America, there are about 130 survivors living in Brazil, Argentina, Bolivia, Peru, and Paraguay. Of course these numbers have decreased dramatically over the course of the last half a century through deaths caused by illness and age.

Those among this group who survived were among the first to cross the ocean eastward after the end of the war. They had families in America, Peru, and Brazil, and were citizens of these countries by birth. These survivors had powerful reasons to return to be reunited with their loved ones.

In the United States, the return of survivors began as early as 1947 and continued throughout the 1950s. In these years the Japanese economy was in desperate straits. Malnutrition was common among young and old alike, and children, war orphans in particular, died of hunger. There were shortages of not just food but also housing, clothes, furniture, and household items of all sorts.

No wonder, then, that the Japanese often envied those who had relatives in America: they received boxes full of items from overseas—not an unusual occurrence in Hiroshima, which had sent so many of its residents to the United States before the war. As some survivors recall, these boxes were oftentimes handed over to a broker, who sold the contents at exorbitant prices. No matter how resentful some might have felt about these transactions, it was impossible to overlook which country was thriving, which not.

3. Survivor's Destinations—North America

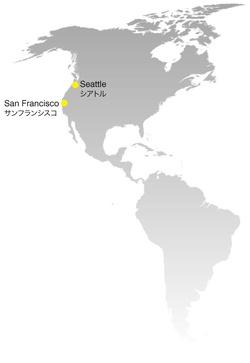

The Northwest Coast, USA

The Pacific Northwest of the United States, including northern California, houses some of the country’s larger Nikkei (people of Japanese ancestry) communities, in San Francisco, San Jose, and Seattle, as well as smaller clusters in the East Bay, Sacramento, and Portland. Reflecting the rich history of Japanese immigrants from the late nineteenth century to the present, survivors residing in this region are diverse in terms of their generation (i.e., first- or second-, or in some cases third-generation Americans), cultural background, and social class. Some contributed to the making of the fruit, vegetable, and flower empire of California; others participated in the industrial or nonprofit sectors that flourished after the war.

Survivors in San Francisco and its surrounding area, along with their counterparts in Los Angeles, were among the first in the United States to come together as a group of “foreign” survivors. Influenced by the long tradition of grass-roots activism among racial and ethnic minorities in this area, including not only Asian Americans but also African Americans and Latin Americans, survivors on the West Coast have been relatively outspoken about their rights. Moreover, through the legacies of the Asian American civil rights movement in the 1970s, which tackled the

problems of community’s poor health and poverty, the Nikkei communities in this region have been able to offer survivors relatively easy access to social and community services. These services include medical clinics, senior centers, and nursing homes especially designed for the Nikkei population. These facilities often support the lives of survivors full of independent spirit. Mizuho B. Stephens is one of these survivors whose life has been deeply embedded in the culture of

the West Coast.

Mizuho B. Stephens

Mizuho B. Stephens is a survivor currently living in San Jose, California. When she came to America in 1963, the only resource she could rely on was her training as a hair stylist, which she had acquired in Tokyo after the war. Born in 1934, she was eighteen years old when she married for the first time, “because people pestered me to marry when I was single.” The marriage, to a Japanese man, did not last long, however, and Stephens explains why: “I could not conceive a child with my husband. I was the problem; I had been exposed to the bomb. But he wanted a son. So he began to tell me, ‘Go see this doctor’ and ‘Go see that doctor,’ barely six months after we got married.” Though she had mixed feelings about this, she was certainly disappointed with the marriage. She wanted to make her life on her own, and this desire led her to come to the United States.

She was eleven years old, living with her parents, two sisters, and a brother, when Nagasaki was bombed. On that morning she insisted on visiting her grandma who lived on the outskirts of the city. This visit saved her life. After the bomb struck she assumed that she was now an orphan, since her parents were at their home in the city, near where the Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Museum is currently located. In the evening of the day of the blast, her older sister who was with her at grandma’s began to cry. Stephens began to cry, too. The next morning they returned to the city to search for their parents, and there they were exposed to the residual radiation.

“Daddy! Mommy!” Stephen’s sister called—and in response their father came out of a shelter, wearing only a pair of summer underwear, a hand towel, and a cap on his head. Soon her mother emerged, her steps trembling. They never discovered the whereabouts of their older sister and brother. Stephen’s father died ten days later from radiation poisoning, her mother seven years later from bomb-illness. After her father’s death, no relatives cared to share food with the surviving members of the family. They had once done so, but no more. Some of their friends bullied them by yelling, “Orphans!”

At first nobody knew that the weapon was an atomic bomb, so people in Nagasaki called it “donpachi,” a term that literally described the flash and sound that accompanied the explosion. People also referred to the bomb as “pumpkin-style” because of the shape of the cloud. Because she entered the city to search for her family, knowing nothing about the effects of radiation, Stephens feels that it was “heartless” of the Japanese government not to recognize her as a survivor just because she left Japan after the war.

After coming to the United States, Stephens earned a certificate as a hair stylist. Later she purchased a salon in order to become eligible for permanent residency. When she was working at a beauty salon in a retirement home, she met her future second husband, who was the manager of the facility. Asked if her survivorhood has ever come up in the couple’s conversation, Stephens says: “He understands the bomb well. It’s just fine—your business is yours, my business is mine. That’s the American way.” The meaning of her survivorhood has changed greatly since her first marriage, which was deeply embedded in and affected by Japanese culture.

*This article is an excerpt from Hiroshima Nagasahki Beyond the Ocean (2014) by Shinpei Takeda and Naoko Wake.

© 2104 Shimpei Takeda and Naoko Wake