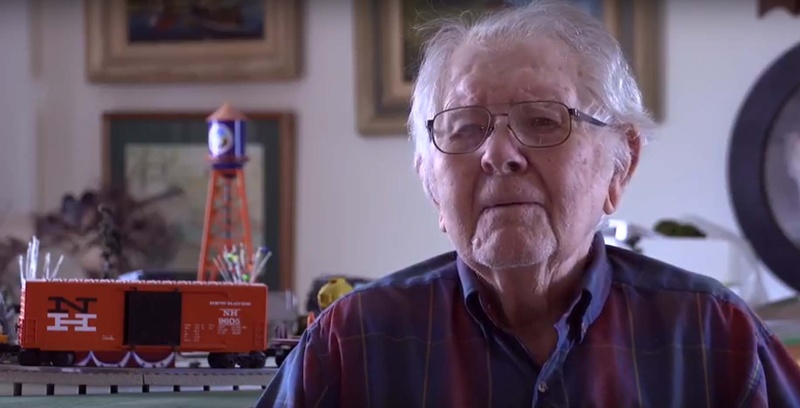

At 94 years old, sprightly Ray Harbold has a twinkle in his eye as he sits in front of his treasured model train set while talking about playing golf up until only a few months ago. The years have slowed his faculties a bit, but there are still vestiges of the strong and agile man who ably ran the family business, Harbold Auto Electric, a Gardena, CA institution that was established just a few years after Ray was born. The business has since closed its doors, but the family still leases the property to a radiator shop that sits on Gardena Boulevard next door to the venerable farming and nursery equipment shop, Yamada Company. On the other side of the former family business is a square, slightly rundown building that currently houses a surf shop. Seventy-five years ago, this nondescript warehouse was the unlikely setting for a remarkable story of loyalty, resourcefulness, and unparalleled kindness.

Harbold Auto Electric was founded in 1929 under the skilled guidance of Ray’s father, Roscoe Harbold, who came to California from Colorado, where he did electrical work in the coalmines. Angered when the Freemasons refused to allow an African American to join, Roscoe and his wife Pearl eventually moved to Escondido, CA, when they heard there was a business for sale a hundred miles north in Gardena. In 1929, they opened the small family shop on Gardena Boulevard.

As a young child growing up, Ray was enlisted by his hard-working father to sweep the floors of the family shop from the moment he was old enough to hold a broom. He says he’s gotten a lot of laughs when recounting this child labor story, especially to people like his good friend Roy Fujii as well as members of the Kuwahara family who ran Yamada Company next door. Matter-of-factly, he relates that half his friends were of Japanese descent.

A humble man who refuses opportunities to boast about himself, Ray is more than eager to talk about the loyal customers who frequented the shop. These friendships started in grade school right up through the war years when they were suddenly hit by the sad news that his Japanese American friends would be, as he puts it, “shipped out.” These were people he considered “good Americans” who were even more alarmed by the attack on Pearl Harbor than he was. Ray remembers his best friend, Roy Fujii, had “tears in his eyes” when they spoke about it.

In the early years leading to the formation of the city of Gardena, Japanese immigrants began settling in the South Bay to cultivate the area’s rich soil for farming, primarily berries. By 1939, Japanese American truck farmers were thriving, and strawberry farmers formed a vibrant community in the area around Western Avenue, north of Redondo Beach Boulevard, sometimes referred to as “Little Tokyo.” As the immigrant community started to profit from the land, they began buying automobiles, trucks, and farming equipment that needed repair. Roscoe Harbold was the only electrician in town and was often called upon to fix the newly acquired machines.

Things changed dramatically in 1942 when Executive Order 9066 forced all Americans of Japanese ancestry to pack up their things and leave the area suddenly for destinations unknown. Following the bombing of Pearl Harbor, Japanese Americans were robbed of their farms, businesses, and livelihoods. During this time of wartime hysteria and upheaval, the sleepy farm community of Gardena saw exploitation by local residents seeking to profit from the departure of a good portion of its populace. With the “yellow peril” advancing and Japanese American farmers being hastily displaced, many in the community offered to take care of the departing families’ properties with no intention of giving anything back. Ray also recalls the people he called “bootleggers” who virtually robbed Japanese Americans of their things by offering outrageously low prices to purchase them, then re-selling them at huge profits.

Thus begins the miraculous, almost too-good-to-be-true story of the Harbold family and how they pitched in to help their good friends and loyal customers. It all started with the warehouse at the corner of Gardena and Orchard that was leased by a group of Japanese American families on the eve of their departure. Like Seattle’s Panama Hotel, made famous by the bestselling novel, Hotel on the Corner of Bitter and Sweet, the warehouse became the repository for clothing, kitchenware, China, photos, art work: boxes and boxes of anything that couldn’t be carried. Stacked neatly in marked off spaces in the giant 50' x 100' warehouse were what Ray remembers as the prized possessions of nearly a hundred Japanese American families.

Holding the keys to the warehouse, Roscoe Harbold became its trusty handler and bodyguard. In fact, not only did he make sure nobody trespassed, he would go as far as to find and ship objects requested by detainees via letters written from camp. It was the job of Roscoe’s teenage son and wife Pearl to find the objects, pack them up, and ship them to awaiting detainees, most of whom eventually returned to find all their possessions safe.

Ray’s memory can get a little fuzzy, especially after having had a few small strokes, and since no one of Ray’s father’s age is left to recollect many details, much remains unclear. What Ray remembers is a big warehouse with individual spaces organized family by family and marked off with chalk or some other kind of marker. Family possessions were demarcated so well, in fact, that when the Harbolds received a letter from an incarceree asking for something they needed, Ray had no trouble finding it in what was a huge space. Family names were most likely listed somewhere within reach so that going to the space provided for each family was easy, or so says Ray.

How the family became so protective of local Japanese American friends and customers can only be attributed to the generosity and kindness of Roscoe Harbold, and like his father, Ray is adamant in his support for the Japanese Americans who he feels did no wrong. “They were loyal Americans, as loyal as anyone else,” he proclaims repeatedly.

Ray points out that other Caucasians in the area also came to the aid of the departing detainees. Fellow truck farmer Carl Paul Pursche stored heavy farm equipment, some newly bought, according to his now 93-year-old son, Roy, who still farms 2,000 acres in Orange County. Roy remembers keeping a pristine Buick for one family and a 1932 De Soto convertible for another, along with half a dozen tractors. All were held in safe keeping until their rightful owners returned after the war.

Pursche says that he had no knowledge of the warehouse on the corner of Gardena and Orchard. Even though they are close friends, he says Ray never spoke about it. Perhaps it had something to do with possible ostracism at the time by local community members for the Harbold’s allegiance to the supposed “enemy.” At a time when suspicion against the Japanese ran high, Pursche understands why it was a well-kept secret.

According to Ray Harbold, none of that mattered because he considered the Japanese Americans his good friends and loyal customers. Although there are not many around who remember what Ray and his parents did for them, old family friend and neighbor Mike Kuwahara of the Yamada Company has heard the story many times and knows Ray well. “He is a man of principle who believes fair is fair. He is a true unsung hero.”

*Note: With a nod to Hotel on the Corner of Bitter and Sweet

* * * * *

Watch Ray Harbold speak about how he and his father helped their Japanese American neighbors:

© 2018 Sharon Yamato