Exodus of Japanese Immigrants in South America

Kami-san was born on March 15, 1922 in the city of Nogata in Fukuoka Prefecture, and in 1993 when he was 11 he moved to Brazil with his parents. At first he went to the Hirano colony and then to the Monte Alegre colony near the Bastos transmigration site and lived in Lins after the war and moved to Santos in 1956.

The Hirano colony is one of the oldest Nikkei settlements established in 1915 and is known as the tragic settlement where 70 or more people lost their lives to malaria which was unknown at the time in just half a year after the arrival. Looking back, the explorers at the time opened up the virgin forests with such a spirit that they were willing to sacrifice anything. Lins, located around the Bustos residential site where Kami-san moved next, also had the largest population of Japanese at the time.

In December, 1941, when Kami-san was 19, Pearl Harbor was attacked. In the following year, the U.S. hold a Pan-American conference of foreign ministers and had 10 participant countries (including Brazil) excluding Argentina pass a resolution to break off any relations with the Axis.

The oppression against Japanese immigrants became stronger immediate after that, and in January 1942, a number of acts was announced such as a ban on the use of the Japanese language in public and a prohibition of traveling and moving without permission of the Security Administration. They were pinned in the residential sites where they were living at the time, and the places turned into a site of isolation and internment.

Since Brazil joined the Allied forces in January, German submarines began attacking Brazilian commercial ships to the U.S. As a counter measure, the Brazilian government started freezing property of immigrants from the Axis countries and starting in April, DOPS (Department of Political and Social Order) captured the main leaders of the Nikkei community one by one on espionage charges and tortured them.

In order to support such inmates, “São Paulo Japanese Catholic Salvation Group” was organized in May, 1942, and they secretly gave support to their fellows during the hardest time of their lives.

It was because then archbishop Dom José Gaspar had their back that such an organization could be organized, when the Japanese were not allowed to get together in public in a group of more than two. They were able to give goods to the inmates with the Catholic church acting as a front. Not only did Brazil accept many hidden Catholic Christians but they also helped Japanese immigrants in general.

Given the ceaseless attacks of German submarines on Brazilian and American commercial ships, on July 8, 1943, immigrants from the Axis countries were ordered to leave the Santos coast within 24 hours. Italian immigrants were exempt from the order, presumably because there were too many, and some hundreds of German immigrants along with 6,500 Japanese immigrants were forced to let go of personal property for little money, the property they had built by saving money for a long time, and were moved by the police under the threat of bayonets.

Not being able to get in touch with their husbands, even pregnant wives and the sick were forced to leave, and a great number of people developed mental illness. It was around the time when Santos Japanese School was frozen. Koichi Kishimoto, a journalist at the time named the matter “Exodus of Japanese Immigrants in South America.”

Persecution of Japanese Immigrants Before and During War Becoming the Cause of Winning or Losing Feud

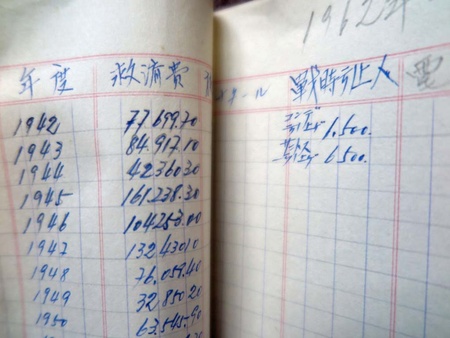

On the report of the Kyusaikai’s activities, in the section titled “Wartime evacuees” there is a note – “1,500 evicted from Conde district, 1942” “6,500 evicted from Santos 1943.” The Group helped over 17,000 people including the poor, the elderly, orphans and those with mental illness from 1942 when it was established (relations with Japan broken off) to 1952 when diplomatic relations were resumed with a Japanese ambassador taking office.

In other words, as a private enterprise, they took on the work of “protecting the Japanese” which was supposed to be a job of diplomatic office.

On the document from the Kyusaikai’s general assembly in March, 1953, there was also this note: first on the number of “lunatics” (the word as written in the original document), of over 7,000 psychotics in the two hospitals in Juqueri and Pirituba in São Paulo, approximately 10% or 700 are Japanese.

In other words, under strong oppression against immigrants from the Axis countries by Valgus dictatorship, Japanese diplomats returned to Japan on an exchange ship in July, 1942 and Japanese immigrants were mentally damaged to the point where a lot of them became mentally ill. I believe that this played a large role in causing the winning or losing feud in the immediate aftermath of the war.

Back in the days, 90% of the Japanese immigrants were planning to go back to Japan proudly with the money they earned in five to ten years. If their intention was to live there permanently, they would have sent their children to local schools and had them adapt to local communities. But they would keep the Japanese style if their purpose was to bring money back to the home country.

Wielding the “Yellow Peril,” Valgus dictatorship led the public to see Japanese immigrants as enemy nationals, and they spent years of life being ridiculed as such by Brazilian people around them.

At the same time, they were becoming homesick and missing their hometown very much. We can imagine that a great number of Japanese people from the countryside, who had never had contact with foreign culture, placed in a situation where they couldn’t return to their home country because of the war, with their longing for a life in Japan getting stronger and stronger to the point where they could no longer function normally.

Even today, there are many expatriate personnel and students abroad, deemed unable to adapt to foreign culture. I myself had a time when I didn’t go back to Japan for about six years. When I did go back after a while, everything in Japan looked new to me, and I was surprisingly moved by the sight of a color copy machine or ATM and delicious looking sweets lining up in a convenience store.

As we all know, regardless of any mental state they were in, no one had a choice of going back to their home country during the war. And when people get oppressed and ridiculed, they foster a hope that they will someday prove themselves right or that someone will take revenge. This led to the delusion that the Japanese military would land and punish the Brazilian government.

So they excessively praise Japan by sending the message, “the Japanese are the best race in the world” encouraging people to keep their self-esteem. This sick mentality is the root of the “winning” state of mind.

Moreover, Japanese papers were terminated in 1941, and the only thing they had was “Tokyo Radio” (short-wave radio of NHK international broadcast) to get information about Japan. Every day it kept playing the announcements of the Imperial headquarters giving the news about Japan repeatedly implying their victory.

Of course, the Brazilian papers that had news stories brought from Western countries reported that it was the Allied propaganda. It was believed among the fellow communities that, actually, the Japanese troops are winning. So when a Brazilian paper reported Japan’s defeat in August, 1945, and even when Tokyo Radio played the announcement of the end of the war from the emperor, the immigrants just could not believe it.

For immigrants, Japan’s defeat meant the demise of Japan and the extinction of the imperial family, causing a big problem of having no place to return and the end of their life plan to go back to their home country with great pride.

Given that, even though they received a lot of information about Japan’s defeat, they weren’t able to believe it. The defeat meant a collapse of their foundation on which they had been standing, and they really wanted Japan to win from the bottom of their heart. They needed a little over 10 years to have their longing for hometown healed and gradually accept their situation of having no choice but spend the rest of their life in Brazil.

Those who were mentally “injured,” after living in the environment where people kept losing their mind and not being able to take it anymore, they probably went extreme on both sides of the winning or losing feud and hurt each other. It would be too harsh to blame them or simply call it an act of insanity.

Had the Japanese government been able to care, those people could have been sent back to Japan but they were simply left on their own. The government probably had no resources at all at the time when they had to take care of a million returning from Manchuria in the immediate aftermath of the war.

© 2018 Masayuki Fukasawa