I’ve been thinking about what we save.

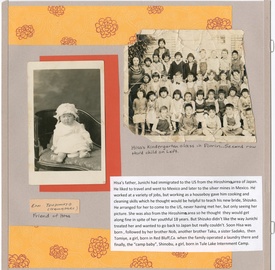

I’ve been looking through one of my oldest auntie’s scrapbooks. Because I know that it will also fall apart eventually, I asked Densho to digitize what would be useful for others historically, so you too can see some of the scrapbook pages here. Like many Nisei women, she kept a scrapbook of mementoes of her life. Not scrapbooks so much as we know them now, with a million accessories and special papers and glue. But a humble scrapbook with black paper photo corners: with photos of herself, letters, mementoes.

The scrapbook survived decades and several moves. There are materials from before camp, during camp, and after camp. However, it was falling apart by the time my auntie’s friend saw it in 2008. She asked my auntie if she could preserve the scrapbook, this time on acid-free paper. She added some decorative papers and embellishments. She asked my auntie about the meaning of the papers that my auntie had saved: who’s pictured in these photos? Which of the young girls in this class picture is you? Where was this picture taken? Why is this picture important to you? My auntie was fortunate to have a friend who wanted to take this kind of care and time with her life and memories. As our de facto family historian, I’m fortunate to have it now.

I find a picture of my auntie working at the camp hospital. I find a hand-drawn illustration by one of my uncles, her Kibei husband, from inside Fort Snelling, Minnesota where he was an MIS interpreter. I find a letter from the Department of Justice, in response to a letter my auntie wrote after my grandfather was taken to Santa Fe, New Mexico. There’s a postcard from my grandfather there, too. I find a picture of my dad as an adolescent, his arms around a friend, with Castle Rock in the background. It’s the first and only picture I’ve ever seen of my dad in camp.

It’s in this scrapbook that I find a different telling of history, even one mediated through the narration and vision of my auntie’s friend. Who is the audience for scrapbooks? They are for the person keeping them, first and foremost, it seems. These are things that we want to remember. These are the things we keep for ourselves.

Scrapbooks are also speaking archives. We have been here, we were here. These are memories we want to give to you.

In my recent work on Japanese American history I have heard of other family archives, other scrapbooks, other treasure chests of memories. I wrote here about the story of the Issei painter Takuichi Fujita, whose sketchbook diary and paintings traveled around the country in a box for decades before landing in an exhibit and a book. I have been reading Karen Tei Yamashita’s beautiful grappling with her own family archives, Letters to Memory. I have just finished looking through the Seto collection of six boxes at the Tacoma Public Library for the first time: titled “Tacoma Japanese American History,” it’s a moving testament to one Nisei man’s grappling with his family history and his community history. Personal photos intermingled with newspaper clippings, and even Internet printouts from pre-camp onwards. Photocopied scrapbook pages, black with toner.

So many of these archives exist, it seems. So many kept secret and in darkness for so long, so many brimming with history, with memories, with—I’ll say it—feeling.

There are families who grew up with decades of silence about camp, and there are families who grew up with whispered conversations about it, and there are families who spoke about it, made art about it, spent their lives trying to recover these histories, to make sure that it never happens again. Call it saving, call it hoarding, call it burying, call it compartmentalizing—but there’s an urgency in all of it. These objects are important, they seem to say. Our story is important. Though I might not have talked about it with you very often, it’s important. I have kept it all for you. This is me speaking my story to you. Are you listening?

What we save? Everything, is the short answer. Because we lost so much.

* * * * *

How we save? That’s a different question.

When I graduated from high school, one of my Nisei aunties took me aside. She wanted to give me my graduation present, she said. We walked into a bedroom near the back of my mother’s house, where I opened an envelope. It contained a card and a check. I was overwhelmed, and said so. “I’ve been saving,” she confessed.

I knew that this gift was no small thing for my frugal auntie, who majored in home economics first in college before going on to earn her Library Science degree at Berkeley and became a children’s librarian in San Francisco. Other gifts have come from my other aunties—my father’s sisters—over the years. Because my father died before President Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, my sister and I were ineligible for the reparations payments. Two of father’s sisters who were still living gave us part of their own redress checks. I hugged my auntie and thanked her.

I’ve been writing about Japanese American history, Japanese American literature, and Japanese American communities for almost twenty years now. I hope my aunties see these efforts as a longer thank-you card.

How we save is important: in small amounts, carefully, precisely, over time. But how we give: generously.

* * * * *

And I have been thinking about how we love.

“Love” isn’t something we seem to talk about in Japanese American communities very often. I am thinking about the bonds among my dad and his five siblings, the bonds that continued even after my dad passed away early, at fifty-two. Every year, my father’s side of the family gathers for an Oshogatsu feast, a tradition that began long before I was born, during the Depression and my family’s sharecropping years, into the present, and my Yonsei daughters can experience that still. A love of gathering, of feeding each other well. That’s a JA kind of love. But I have been thinking about love in these terms: what we save, how we save, and how we give.

For the last several years, I have been working on Japanese American public history efforts in Tacoma and on Vashon Island. I have been working on my own book as well as a co-authored graphic novel on camp history with Frank Abe. In thinking and researching and feeling my way through so much Japanese American history, I have been transformed. And very early in the process somehow, I began to see these as tellings of history: what these scrapbooks and archives say and what they do.

All this time I’d been thinking about the love of the Issei for the Nisei and later generations, all that they did to build a better life for their children. That’s a more conventional way of thinking about kodomo no tame ni. But recently I have also seen the love flowing back through generations, from fourth to third and second and even first and back down to fifth and sixth. From my sister Teruko’s artwork on our family barrack at Tule Lake, my cousin Soji’s Grateful Crane Ensemble to Laura Misumi and Jessica Yamane’s piece “We Remember” to Brandon Shimoda’s work on the physical camp sites,” Lauren Iida’s paper cut work, Emiko Tsuchida’s Tessaku project, Kayla Isomura’s The Suitcase Project, the Yonsei Memory Project, Kishibashi’s documentary in progress, and so many others—I have seen the ways that the love flows in different directions. We hear the memories.

And if we might not really “remember,” we are not forgetting, either.

Recently I wrote a short monologue about that kind of love from the point of view of a young middle-school girl. The words at the end are my cousin Soji’s, used with his permission.

NARRATOR -

Can I tell you something special about kodomo no tame ni?

I used to hear it all the time when I heard about camp history. I used to think it was a one-way street, the Issei parents showing sacrifice and love for the sake of their children. The grace to endure what seemed unendurable: gaman.

Now I know the magic of JA kodomo no tame ni. It’s not a one-way street. In fact, the more appropriate comparison might look like this crazy crosswalk in Tokyo, called Shibuya Crossing. You might have seen it in movies, sped up and frantic.

You should take time to watch it in slow motion, though. It’s actually beautiful.

For Japanese Americans, for kodomo no tame ni, that’s how love works. It moves in all directions, from parent to child, back from grandchild to grandparent, from daughter and son to father and mother, to all the kindred and chosen “aunties” and “uncles.” It’s a collective, community act.

Resistance works the same way: it can move in a lot of directions. It can come from unexpected places.

I’ve been mad about so much lately. There’s so much that feels wrong in the world right now. I hate not knowing what I can do. I'm just a kid.

But then I think about something my cousin told me once. I was nervous about speaking in front of hundreds of people, and I’d never done that before.

“When I get nervous,” my cousin told me, “I think about our grandparents, standing by an open door.

“They are smiling and beckoning to me.

“‘Please, please, go in! Walk on through,’ they say.

“It’s what they wanted for us.

“Walk on through.”

© 2018 Tamiko Nimura