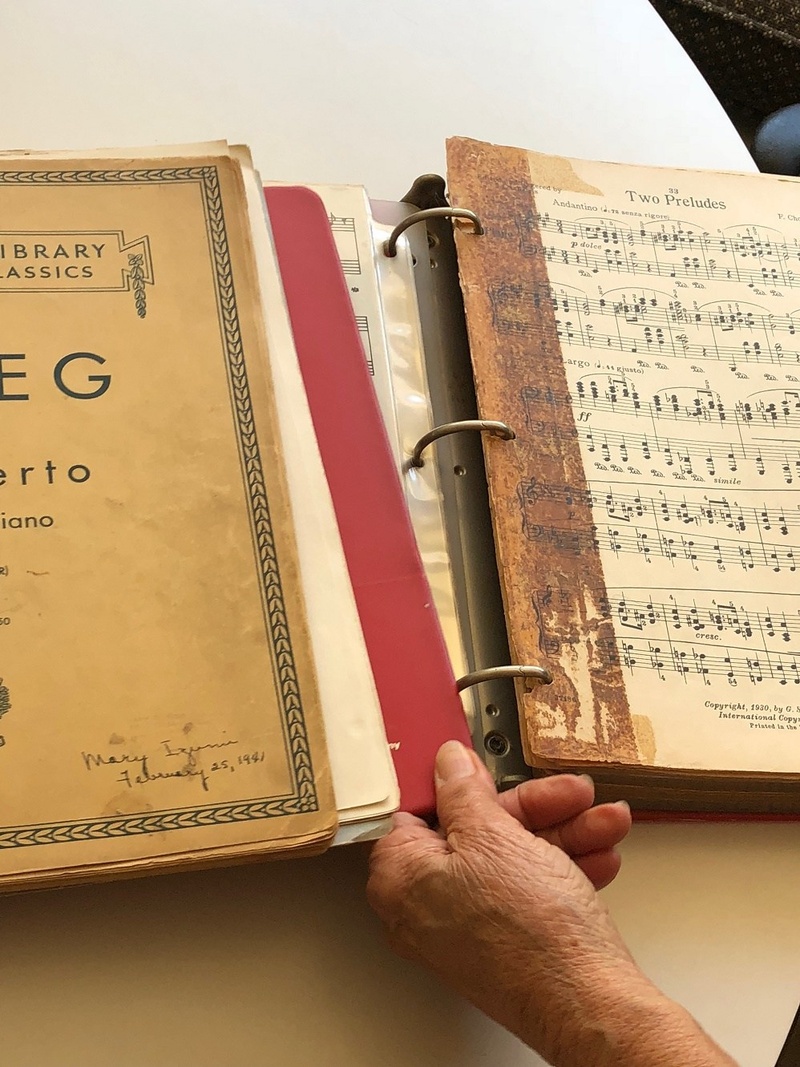

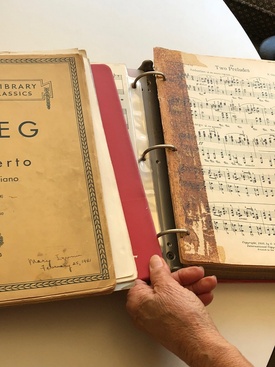

Inside her home in Southern California, Mary Izumi sits at her piano flipping through the yellowed pages of her old songbooks. Along with her high school yearbook, they are the last remaining artifacts from her time growing up in a Japanese fishing village that once thrived on an island in the ports of Los Angeles before it was destroyed at the onset of World War II.

After the attack on Pearl Harbor by Japan on Dec. 7, 1941, claims of treason and disloyalty were launched against Japanese-Americans living across the country.

Japanese community leaders were rounded up and jailed the same day. Soon after, families were forcibly evicted from their homes and sent to concentration camps.

They couldn’t have known it but the Japanese villagers on Terminal Island – a man-made island nestled on the coast between San Pedro and Long Beach – would be the first community on the West Coast to bare the brunt the country’s racist fear.

Furusato

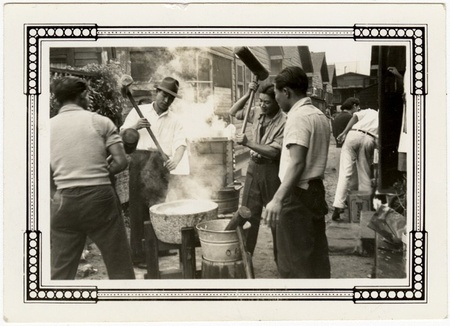

At dawn, fisherman launched their ships from Terminal Island and flung their nets into a blue surface teeming with sea life. Other men used a more traditional method: thrusting long bamboo poles into the water and flinging large tuna over their heads and onto their ships.

The men unloaded their catches of sardines and tuna into the Van Camp Seafood and American Tuna Company canneries, two companies that together produced most of the country’s supply of canned seafood in the first half of the 20th century.

After dropping their children off at Walizer Elementary School, mothers streamed into the local fish canneries and shipbuilding warehouses for work.

After school, children learned judo and kendo at Fisherman’s Hall. They walked along Main Street, trickling into candy shops and storefronts where vendors sold traditional Japanese goods.

On Tuna Street, fishermen bought supplies, home goods and homemade sake from Hashimoto Hardware. Outside the store, men made mochi rice cakes for New Year’s celebrations.

The boys would go clam hunting with their fathers while the girls would learn Japanese dances and prepare for Emperor’s Day celebrations.

On days when fishermen returned home, families would picnic at the beach.

The more than 3,000 first and second-generation Japanese villagers that lived in this community called it the “old village,” or Furusato.

Izumi, 93, was raised in one of the homes that cannery companies rented to their employees.

“It was a cohesive community with no crime. Everyone depended on each other,” Izumi said. “If people had extra food they would share it.”

Everything changed after Japan attacked the U.S naval fleet at Pearl Harbor.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066 authorizing law enforcement to round up over 120,000 people of Japanese descent – two-thirds of whom were U.S. citizens.

In a wave of fear and anger that swept the nation, Izumi’s father was one of hundreds of Terminal Island men arrested and jailed.

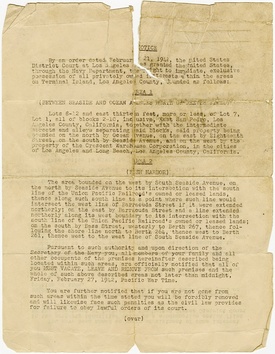

Weeks later, a notice appeared on a telephone pole on Main Street. The notice – dated Feb 25, 1942 and signed by a U.S Navy captain – ordered all Terminal Island residents to leave their homes within 48 hours.

Soldiers patrolled the streets as mothers scrambled to figure out where their families would sleep in the days to come.

“We had no cars to move our things and the government arranged nothing for us. It was the most traumatic thing,” Izumi said. “We were stunned.”

The island was suddenly flooded with “opportunists” who made below-bargain offers for the furniture and appliances of desperate evacuees, Izumi said.

“[Villagers] got mad and banged up their fridges, beds and other belongings to pieces rather than sell to these people,” Izumi said.

Cafe and grocery store owners sold their appliances. Fisherman sold their nets. Izumi, who said she wanted to be a pianist, sold her piano – given to her by a wealthy friend of the family – for only $5.

Luckily, Izumi said, a team of quakers and volunteers from Baptist churches and Buddhist temples showed up to help villagers transport their belongings to wherever they were staying next.

A gang of bulldozers showed up soon after the island was evacuated, sinking their teeth into the villagers’ soil and razing homes, shrines and businesses to the ground.

Within a couple months after the forced removal, the community was obliterated.

After the demolitions, the only sound from the once bustling village came from the footsteps of armed patrols.

Rattlesnake Island and Other Names

Kaz Okada, a Japanese-born resident of Los Angeles, is on a fishing boat drifting along the edges of the port of San Pedro.

He is here because he was pulled in by the history of Furusato and by the similarity between himself – an avid fisherman – and the villagers.

“Just like [previous Japanese migrants] in Terminal Island, I took my suitcases and left my country to stake out a life in this new territory,” he said. “I sense similarity in us, in our bloods.”

Okada said he felt an “amazing web of coincidental but deeply interconnected energy” emerging from the island while he was near it.

He said it might be the similarities between Terminal Island and the city he was born in: Nagoya, a city that also has heavy industry and a large port. Maybe some other forces are at work, he said.

He said he was stunned when he realized the local fishing company he contracted with to go out on the water is located on Nagoya Avenue.

From the fishing boat, Okada looked upon the island and populated it with the images, smells and sounds he gathered from his research on the village.

He knows the island has had other names and histories carved and reshaped by those who happened to populate it at that time.

The Spanish called it the Isla Raza de Buena Gente. It later transferred to Mexico after the country gained independence from Spain in 1821.

When the United States defeated Mexico in the Mexican-American War, they renamed it Rattlesnake Island. It was also referred to as Deadman’s Island.

The small Japanese fishing community strewn across a grey, industrial landscape and the clangor of ports – fishermen, cannery workers, shipbuilders and their families – made a life for themselves until a wave of xenophobia and war-fueled hysteria crashed their ships on the rocks, destroyed their village and forced them into internment camps.

Today, the island – locked in by Long Beach to the west and San Pedro to the east – is covered by a patchwork of industrial sites, restricted areas, shipping warehouses and a prison that has housed its share of famous and infamous criminals over the years.

Chicago mob boss Al Capone spent the last few months of his 10-year sentence for income tax evasion at the prison. Serial killer Charles Manson did two stints there before his 1971 conviction for mass murder. Hustler publisher Larry Flynt spent time there for shouting at a judge.

It’s difficult to access most of the island, unless you work there or have security clearance.

Across the channel, San Pedro, a port city with strong working-class traditions, is a more convenient vantage point from which to view the island.

Former islanders and their families rose up in anger when the city announced plans in 2011 to develop its oceanfront.

They said the plan would demolish the last remnants of the fishing village and cannery industries, and instead lobbied for preserving the place and the histories of the people that lived there.

Eventually, the Los Angeles Board of Harbor Commissioners bucked under the pressure and unanimously approved a plan that preserved historic buildings from the old village.

‘No Home to Go Back To’

In January 1945, Roosevelt’s exclusion order was rescinded. Japanese internees were released, given $25 and a ticket home. When they returned they found no trace of their community.

“There was no home to go back to,” Izumi said. “It gives me this empty, lonesome feeling inside. It’s a very hard thing to accept.”

Izumi said some villagers went back to work at canneries still in operation. But most left their old community again and scattered across the country.

Some islanders tried to stay in touch and keep the old bonds intact. A group called the Terminal Islanders Club, made up of former residents and their descendants, celebrated its 45th anniversary in 2016.

The main visible symbol of the historical fishing community – and its contributions to the region – is a memorial site established in 2002 by children of former residents. They set up the memorial on Seaside Avenue to honor their parents and preserve the memory of Furusato.

The memorial is a reminder of what should never be done again, Okada said.

It’s not lost on him as an immigrant that “in this current political climate,” the relevance of the forced removal of the village has a heavier weight to it.

“If something like that happened again, I would be taken,” he said. “Bulldozing this life, this entire community in a non-negotiable way, it’s scary. It cannot be undone.”

Out on the water, he thought about the “spirit” of the old Japanese village’s fishermen. He wondered if the ritual they dedicated themselves to had the same kind of impact on their lives as it has had on his.

“I, at times, liked to think of my fishing as a ritual to free my soul,” he said. “And perhaps their souls in a way.”

* This article was originally published on the Courthouse News Service on June 12, 2018.

© 2018 Martin Marcias Jr. / Courthouse News Service