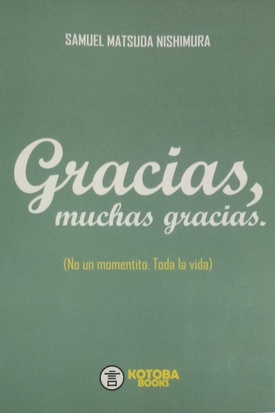

When he turned 72 in 2013, Samuel Matsuda Nishimura published a book titled Thank You, Thank You Very Much . It was an autobiographical work in which he remembered his childhood, his parents and siblings, talked about his wife and children, and which he punctuated with jokes.

The title was not free. If the book had to be translated into a gesture, it would be like an oceanic hug of gratitude: to family, friends, God, life...

Don Samuel considers himself a lucky man because of the love that surrounds him and that has accompanied him all his life, since he was born in the back room of the encomendería of his parents, a couple of Okinawan immigrants, in the modest neighborhood of Santoyo.

There was not enough money in his home, but he had a happy and peaceful childhood. In Santoyo there were many families that came from the same Okinawan town as his father. And like him, they had encomenderias. Although in theory they were competition, Don Samuel remembers that if one lacked salt or sugar, he would ask a countryman. “That was what we learned as children: to live in community and solidarity,” he says.

The Matsudas also had luck with their Peruvian neighbors. On May 13, 1940, when angry masses looted the stores of Japanese immigrants in Lima, a Peruvian family protected them and prevented the looting. The relationship was so close that three sisters from the neighboring family were godmothers to Don Samuel and his two older brothers.

Unlike other post-war Nisei children, he did not suffer discrimination. In Santoyo and in the neighborhood of the La Victoria district where they later moved, where their parents had a small cafe (a typical business for Japanese families), they always got along well with the neighbors.

The Nisei had a good reputation as students. He was no exception. In the Great Melitón Carvajal School Unit, where he studied high school, he and another Nisei alternated year after year in first and second place in the promotion. The positive image of the children of Japanese was evident when they were proposed to occupy positions of responsibility, especially in the management of money. “The Chinese, the Chinese treasurer,” it was said in those times.

For him, football was a powerful instrument of social integration. A baseball player since he was a child, he made friends in the neighborhood at a time when playing with a ball was a luxury and sometimes there was no choice but to use a ball made from socks.

His passion for the game brought him spankings that he still laughs about to this day. One day there was no ball to play with and he offered to make one... with his sister's new socks. “Wow, he chased me around and beat me to death,” he remembers. Another day, he broke some school shoes his father had just bought while playing soccer. The game was suspended when his father found out and began chasing his naughty son with belts, while the neighborhood watched the surreal spectacle.

“DON'T DO A WONDERFUL THING”

A common memory in all Nisei is the hard work of their parents. The Matsudas' business was always open, including Saturdays and Sundays, and throughout the year it only closed one day: May 1. However, that did not mean that they stopped working, because that day they carried out an exhaustive cleaning of the premises (walls, tables, chairs, floor, etc.). In other words, they never rested.

His mother and sister served the public, while his father was in charge of shopping. He and his brother studied on weekdays and on Saturdays and Sundays they helped in the store.

As in most Japanese homes, there were no gifts and more work was done at Christmas because the clientele increased. The most precious asset, the best toy for Don Samuel, was always the soccer ball.

Their parents were not ones to sit their children down and fill their heads with instructive words about life. You had to work hard and, in addition, you led by example. "The only thing they said was: 'Don't do something bad, don't do something bad.' Everything was there,” he remembers.

They were times of tanamoshi and the word as the only guarantee of payment, without signed papers. “You could stop eating, but you couldn't fail at tanomoshi. It was sacred,” he says. Remember the case of a Japanese man who could not honor his debts due to the collapse of his business. He went to the Peruvian jungle, worked for four or five years and returned to Lima, where he visited his creditors house to house to pay off his debts with interest (as if that were not enough, he also brought omiyage).

WHEN TIME PUT THINGS IN THEIR PLACE

Samuel Matsuda cannot speak Uchinaguchi, but he understands it because his parents spoke a mix of Okinawan language and Spanish to him. Most Okinawan immigrants did not speak Japanese, he remembers, and there were differences between them and immigrants from the rest of Japan, who looked at them with a certain feeling of superiority. However, this distance, notorious among the Issei, was not transferred to their Nisei children.

“More than Japanese, Uchinanchu is ingrained in me,” he says. He has visited Okinawa four times, where during the prewar two children were born to his parents before migrating to Peru.

Although his parents got along well with their Peruvian neighbors and clients, there was a distance, at first unbridgeable, that they established between the “nihonjin” and the “dojin”, a term commonly used in the Japanese colony at that time that was used to refer to Peruvians.

Therefore, the Matsuda home suffered a shock when the parents learned that their 16-year-old daughter had a boyfriend without Japanese ancestors. The couple did patient and tireless work to win over the parents. They succeeded and got married, but the social pressure, what people would say within the family and the Japanese community were so strong ("how can you marry dojin ?") that the parents did not attend the marriage, despite agreeing with he. Of course, they encouraged their children (Don Samuel and his brother) to participate in the ceremony.

Don Samuel highlights that his brother-in-law won the hearts of his family. Almost 70 years later, the couple is still together. Time proved love right and defeated prejudice.

HUMOR TO THE TEST OF EVERYTHING

Traumatized by the experiences suffered during the war (looting, deportations, closure of schools and institutions, etc.), the Issei did not want their children to enter politics. When Don Samuel, as a member of a group of young Nisei university students called Generation 64, participated in the organization of a forum of candidates for the presidency of Peru in 1962, his father reproached him: “No, not politics.” “The times are changing,” he replied.

The event attracted the attention of the political parties that competed in the elections, attracted by the “one hundred thousand votes” of the colony, and of the national media. However, few Nisei attended. Politics was still a taboo subject.

It was as a politician, much later, that Samuel Matsuda lived an extreme experience. As a congressman of the Republic, on December 17, 1996, he attended a reception offered by the Japanese ambassador to Peru at his residence on the occasion of the birth of Emperor Akihito. He did not leave until 126 days later, on April 22, 1997, during which he was one of 72 hostages held by a terrorist group.

Experiences as hard as that can transform a person, constitute a turning point in their life. In the case of Don Samuel, who also worked as an analyst at the Japanese embassy and was director of the newspaper Perú Shimpo , this was not the case. He suffered more for his family. “It was a four-odd month slump. What I felt most was the suffering it brought to my family. In reality, I think the family suffers more, because they don't know what is happening to them. They imagine thousands of things.”

Family has always been the most important thing in his life. When he says he had a happy childhood, he is not referring to material comforts (which he did not have). His happiest childhood memory is not a birthday, a toy, an academic or sporting achievement at school, but a feeling: “I always felt safe and protected.”

In addition to his parents, he had his older brothers. “My brother was crazy for me. “My sister was like my second mother,” she says. “It's the good thing about being part of a very united, very supportive family, where you breathe affection and love.”

Raised in such a family, when he became an adult he poured all that into the family he built (his wife Angelica and his children Samuel and Angelica).

He says he is proud of two things. The first, “of the family I had and the family I formed.” And the second, “that no one can point out me, or my people, for something improper.”

“It's the luck I've had in my life. The only setback has been the hostages thing. Afterwards, everything has been a well-paved track.”

It has been a well-paved track not because life has handed it to him on a plate, but because of the positive attitude with which he faces things, his bonhomie and his proverbial sense of humor, which emerges even in the most difficult circumstances.

Nine years ago he defeated cancer. After an eight and a half hour surgery, he woke up once the effect of the anesthesia had worn off. What happened next is narrated in Thank you, thank you very much : “I heard a whisper: 'Don Samuel, can you hear me, are you awake?' I barely opened my eyes, saw the diffuse silhouette of a face and asked: 'Who is speaking, Saint Peter or Satan?' He answered me laughing: 'I'm Dr. Tito Li.' He was one of the five doctors who were in the operating room. I closed my eyes and said to myself: 'Damn, I'm alive!'

© 2018 Enrique Higa