I was conscious of being different, but only in the sense of looking different.

—Ben Furuta

Ben Furuta was only four when his family was forced out of Oakland, California, and incarcerated at Poston during WWII. “I have only flashes of memory, little incidents,” he says, like an image of his father with bandages on his arms, covering chemical burns he received at his camp job, working in the camouflage factory. He remembers older boys, teenagers or young men, who told stories of rattlesnakes in the shade canopies that “scared the bejeezus” out of the little kids.

The family only spent about a year at the concentration camp, after which they moved to Minneapolis on indefinite leave. Furuta’s father and uncle worked together growing bean sprouts to sell to Chinese restaurants. Once the war ended, they planned to move back to California, but instead, they stopped in Denver to visit another uncle and stayed. That’s where Furuta’s childhood memories really begin. In Denver, he and his family were part of a small but vibrant Japanese American community that he remembers revolving around two churches, Methodist and Buddhist. Furuta’s family belonged to the Methodist church, which sponsored a Boy Scout troop that he joined. He and his friends camped and played sports, and each year on Memorial Day, his family friends got together for a picnic and day at the park.

While Furuta was in high school, the Air Force began working to establish an academy nearby. He had always been interested in airplanes, so when the academy opened to applications just before his senior year of high school, he applied and was selected. His mother was not very expressive about his acceptance, but his father, on the other hand — “while he never said it, I’m sure he was really, I guess I wanna say proud,” says Furuta. “I was a little upset at him because he opened up the telegram that told me that I was accepted. I said, ‘You did what?’ And he was kind of jumping up and down. I know they were happy that I was accepted. You know, a little success on the part of their offspring.”

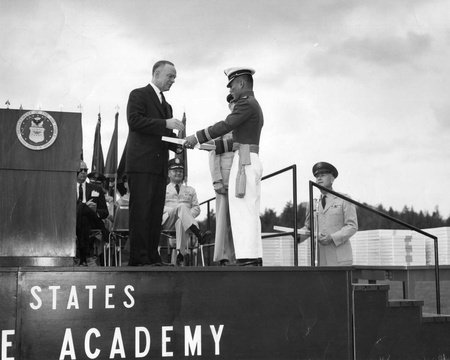

When he started at the Air Force Academy in 1956, in its second year of operation, Furuta became its first cadet of color, though he’s quick to disclaim that he doesn’t have written record of this, only his observation. “I was conscious of being different,” he says, “but only in the sense of looking different. What I remember is that I was accepted as a member of that class without question, and no one ever brought up the fact that I was ‘different’ or looked different or came from a different ethnic group.” At a recent reunion, he mentioned that feeling to a couple of his former classmates. One of them responded, “Well, we just took you as another one of the guys,” which validated for him that, at least among his friends, he belonged. “At the same time,” he says, “I realized I was different. Because, obviously — one of the jokes at one of my previous reunions was I’m the only one here that doesn’t need a name tag, if you know what I mean.”

At the academy, Furuta lived a regimented life of military training and academic classes. Especially during his freshman year, he and his classmates had a long list of rules to follow. When upperclassmen passed by, they had to stand against the wall to make way. During meals, they sat at attention, straight up with their eyes forward. They kept their beds made and their clothes hung precisely. “We had a certain amount of specific knowledge that we were responsible for, such as members of the government, the Air Force leaders, and Air Force history,” he says, “and we were expected to spout that stuff off at an instant.” Falling short in any of these ways meant demerits. A certain number of demerits meant “confinement to quarters” or “walking tours,” a formal term for marching on the quadrangle, back and forth, carrying your rifle, for an hour. But the cadets also went to football games, had dances with women from the local colleges, and Furuta phrases cagily, “found ways of shall we say, enjoying ourselves,” which after some prodding he translates to parties “in places other than the academy.”

After graduation, Furuta attended Air Force pilot training in Florida and Arizona, then in 1962 was assigned to a weather reconnaissance unit in Guam. The job involved making daily routine patrols, to monitor weather, keeping an eye out for storms like hurricanes and typhoons. He flew a WB-50, a long-range bomber (“an offshoot of the WWII B-29 bomber”) modified for weather reconnaissance, which carried a crew of ten, including two pilots, a flight engineer, a weather observer, scanners, and radio operators. Most of his patrols weren’t dangerous, except for one: Typhoon Karen, a Category 5 storm that blew through Guam in November of 1962 and remains one of the most destructive in the island’s history.

Monitoring Karen meant flying out early enough to penetrate the eye of the storm at 8 a.m., then flying around and penetrating it again around 4 p.m. before flying back to base. To reach the eye of the storm, Furuta’s crew had to fly through the wall cloud, the most turbulent, high-pressure zone immediately surrounding the eye. “The best way to deal with a wall cloud is to hit it perpendicularly because you would get through it very quickly,” he says, “so you would be in the wall cloud for really only a few moments. And then once you got into the eye, usually it was clear, in the sense that you could actually see the sky. We would fly around it, take the measurements that the weathermen needed to take, and then line up and go perpendicular back out.” They survived (“obviously”).

After fifteen months in Guam, Furuta was reassigned to Japan, where he lived on the Yokota Air Base in Fussa, Tokyo. Before living in Japan, the most Japanese people he’d seen in one place were in Los Angeles’s Little Tokyo during Nisei Week. Even there, compared to Denver, he’d thought, “My god, there are all these Japanese people around.” In Japan, for the first time ever, everyone looked like him, but his language skills quickly gave him away as an American. He remembers one incident in Shinjuku Station: “I was walking down one of the walkways to get out of the station and I feel this tap on my shoulder, so I turn around, and there’s a lady there and she begins talking to me in Japanese. And I told her in my broken Japanese, ‘I don’t speak Japanese,’ and the look on her face was just amazing like, ‘You look like you’re Japanese.’”

In Japan, Furuta met and married his wife, Hideko, a distant cousin who came to meet him partly because she was learning English. He left the Air Force in 1965, before fighting escalated in the Vietnam War and it became more difficult to leave the military. “Six or eight months after I got out, they essentially said to other people of my generation, ‘You can’t leave,’” he says. His main motivation for leaving, though he says he could have just as easily decided to make a career of the Air Force, was that he wanted to go back to school to become a teacher. After returning to the U.S., he received his credential from UC Berkeley and started teaching in the Oakland Unified School District, before relocating to Southern California, where his parents had moved while he was at the academy.

Now, though he has retired from teaching, Furuta continues educating kids as a docent at the Japanese American National Museum. Unlike his class at the Air Force Academy, the classes that come through his tours are very diverse. “Especially where we are located, the people who come for these tours are really linked closely to immigration,” he says. “And so what I’m hoping will happen is by hearing the story of Japanese immigration and the incarceration, they will begin to appreciate their own history of immigration and start thinking about immigration issues and questions.”

© 2018 Mia Nakaji Monnier