“I think that generation isn’t like our generation that grew up with the thought that we’re all equal. I think they understood it but they also knew that their parents were immigrants, and so they weren’t quite ‘up to par.’ Then of course what happened with Pearl Harbor just destroyed their lives. And they would forever be associated with the enemy.”

— Teresa Maebori

Educator, author, and Philadelphia JACL board member, Teresa Maebori, started to retrace her family’s WWII experience when she asked her 98-year-old mother to join her on a pilgrimage back to a town near Boise, Idaho called Caldwell. It was where her parents spent the war years doing hard, manual labor to support a vital war effort: the harvesting of sugar beets. But perhaps the stronger drive was to be in control of their fate as a young family. In a cruel and unusual twist of timing, her parents had just been married shortly before Pearl Harbor. “They were married on November 22, 1941. And two weeks later, it was Pearl Harbor. So they began their married life in a concentration camp,” Teresa says.

Teresa’s older brother was born in Tule Lake, while she was born in 1945 in the labor camp. In retracing their family’s past, Teresa and her younger sisters came to realize that their mother went into Tule Lake pregnant, surely affecting their decision to leave. “We were trying to imagine what she must have felt like going in there, in those conditions. Not realizing what kind of medical treatment she would get and how she would care for this child. So they soon realized that if they could get out, they’d get out.”

Teresa’s efforts to shed light on the labor camp experience was covered in a piece by the The Inquirer, which wrote an entire profile on her efforts to bring a traveling exhibit called Uprooted to Philadelphia.

* * * * *

I was born in the labor camp. My older brother, who was two years older than I, was born in Tule Lake. In that discovery, I didn’t really know about the labor camps. My parents didn’t really tell me about it and I knew that they had gotten out of Tule Lake but what they said was they were sponsored by a farmer. So I was born in Caldwell, Idaho and on my birth certificate, I’m searching for the farmer’s name or sponsor’s name. My mother was still alive at that point [in 2014], she was 98. So I said, ‘Would you like to go with me?’ And then at the same time that I was writing an article about our experience, I discovered Uprooted online and it said it had a traveling exhibit.

The exhibit was a resounding success and it was the first and only exhibit on the East Coast of the labor camps. But when I went into the Uprooted website and I learned all this historical background, my mother did not know much about that either.

My parents had just been married, they were married on November 22, 1941. And so two weeks later, it was Pearl Harbor. So they began their married life in a concentration camp. This summer, my sisters and I went to Tule Lake because that’s where they were incarcerated and we realized that my mother went into camp pregnant because my brother was born in Tule Lake. So we were trying to imagine what she must have felt like going in there, in those conditions. Not realizing what kind of medical treatment she would get and how she would care for this child. So they soon realized that if they could get out, they’d get out. So that’s why they volunteered for harvesting sugar beets.

Were they farmers before that?

No.

So this was new for them.

Well, my father was a jack-of-all-trades. He had been a person who worked with his hands. He graduated from high school but didn’t go onto higher learning. My mother however graduated from the University of Washington and she had a BA in what we could call Home Economics. I forgot exactly what it was. She was really good at sewing and she liked design. One of the things she had told me before was when she graduated from college and went to the college counselor and the counselor said, ‘Well I don’t know why you went to college because there are no jobs for you. You’ll never get a job.’ Because you know, opportunities for women but opportunities for women of color were just not there. And my father worked for his brother-in-law in a pottery in Auburn, Washington.

So they volunteered to work in sugar beets and so they were assigned to Caldwell, Idaho. And fortunately Caldwell was a camp that had previously been created because of the migrant workers from Arkansas and Oklahoma from the Dust Bowl and the Depression. And so they had moved out West to seek their fortune because there was nothing where they were. So the federal government created these low-income housing, basically.

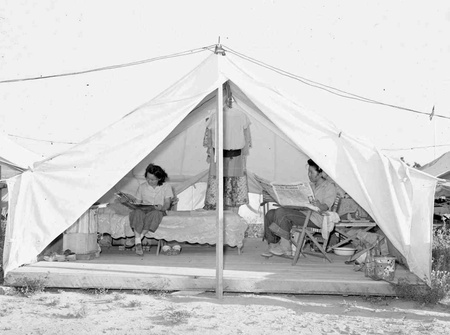

But when the war came, they didn’t need to work in dirt beet fields because the war industry was all stoked up and I’m sure some of them volunteered to join the military. So those camps were empty and what I learned is that the labor camp movement happened for the sugar beets because they had no workers. And the Amalgamated Sugar Company lobbied to get workers and so the farmers said, ‘Well, there are all those Japanese in those camps.’ So they recruited and luckily my parents were assigned to Caldwell. I say luckily because many of the people who left the concentration camps were considered seasonal workers, so they lived in tents. They had a wooden floor and they had tents. I think they went when they had to plant and then the harvest was over, and they went back to the camps, which sounds horrible.

Awful conditions.

Yes. So when we went, the labor camp still exists but it’s now low-income housing. So this is the footprint of the labor camp. [Teresa points to various photos]

These were barracks for single men, and these are now the new homes because I think in the late 50s/’60s they tore down the original cottage and constructed these fourplexes. So that’s what they’re like now. But this building still remains, and it was the post office, the market and the employment office. And the other structure that’s still left is the water tower. So Michael Dittenber is the director there, so he gave me the history and took us around.

They had assembly halls, they had schools. And I was amazed, at the vegetation and they had playgrounds. So when the Japanese Americans came, this shows them living there. And some of them didn’t leave until the late ’50s because many of them had nothing to go back to. And I think they knew they had housing, and they knew they could get employment.

And are these all family photos? So no one came into document the living quarters, correct? These are all family photos?

Yes, this wasn’t documented by Russell Lee. These were the family photos. So it was fascinating. So that opened everything up and I talked to my mother about it and I asked, ‘Do you remember this, do you remember that?’ And she said ‘No I don’t because I was taking care of two infants.’ And then I thought too, I wondered how much she was traumatized by this whole thing and didn’t want to remember.

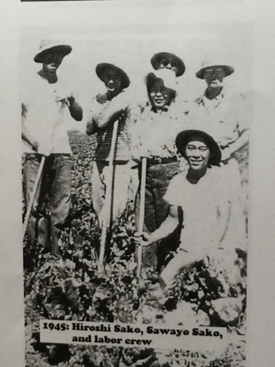

I do mention in the article that she remembers that the Matsuis were there. Robert Matsui, his family was in the labor camp but they were really fortunate because once they were in that labor camp, they did not have to go back to Tule Lake. I don’t know what they did in the off-season but I imagine they had things to do. My dad was a supervisor. He became a supervisor and one of the stories I told when I took people through the exhibit is that there are often pictures of them gathering up the workers to go out to farm in these pick-up trucks. And my mother said one of the things she does remember is that my dad and she would kind of chuckle because many of the workers were young kids, young guys from San Francisco and Los Angeles and they had no idea what a hoe was. They had never done that kind of work. They did not know.

That must have been shocking for a lot of them.

It was, a big shock. They didn’t grow up on a farm. Many Japanese Americans did but many didn’t.

Did your father pass a little earlier than your mother?

My dad died when he was 65. He had a stroke ten years earlier and a series of small strokes and heart problems. So he died in the ’80s. But my mother lived until 2014 when she was 98.

And did you ever talk to your father about this?

Not really. At that time, I was probably in my mid-thirties and it wasn’t part of my consciousness. I knew it but I wasn’t really totally immersed in it, and so I didn’t ask a lot of questions. And as you know, people didn’t really talk about it. I think people’s consciousness began to be raised when the Commission came out and I think people felt an obligation to speak up. So I think when they began to hear other people’s stories they felt it was all right.

What do you think that’s about? I’ve heard that over and over, that people felt less shame around sharing even though everyone knew it was wrong. But it was only when redress was officially given then the community could finally start healing.

Well I think the community began to heal when people began to testify, when there was attention to it. Of course there was lots of controversy, people said ‘Why bring this up? This is past. We need to move on.’ I don’t know if you know about Philadelphia but we had some very strong people here, one being Grace Uyehara. And Grace was the lobbyist in Washington for redress. She was a mover and shaker, she was an amazing person. And Judge Marutani who was the only Japanese American on the Presidential Commission, he’s from Philadelphia. So Philadelphia was a very strong group of people who believed in it and believed that something could be done. Not everybody agreed but there were determined people.

One of the comments my mother made was that she never thought that the government would ever apologize. So the most meaningful thing for her wasn’t the money, it was the apology to say that it was wrong, to admit that. Because Japanese Americans are such a small proportion of the population. I lived here when all that strategizing was taking place and they thought that could never happen, that we didn’t have enough power.

But through the efforts and willpower of Grace, basically, she brought together coalitions and she got involved with the Civil Rights Coalition of D.C. They found out that Jim Wright, who was a Senator from Texas, they were able to get him on board because the 442nd rescued the Lost Battalion and they were from Texas. And they’re revered in Texas, so he was for it. So they keyed in on various people because they knew they could get California, Washington and Oregon, they knew that. But where else could they go? So they worked that.

* This article was originally published on Tessaku on February 3, 2018.

© 2018 Emiko Tsuchida