The first group of Japanese arrived in Hawaii in 1868. This group is known as gannenmono, or, “first year men,” because they arrived in Honolulu in the first year of the reign of Emperor Meiji. This was a small group of about 149 laborers. Within three years working in the sugar plantations, most returned to Japan. Some went onto the mainland. About fifty remained. These gannenmono were truly the first Issei.

One of the original immigrants was Sentaro Ishii. After his arrival in Honolulu, he was assigned to Maui and the McKee Ulupalakua Plantation. Ishii described his work as being “not bad…they treated the laborers kindly.” He eventually became a cook and lived his life at Kipahulu. In later years, because he learned and became fluent in Hawaiian, Ishii became a luna of Hana. Ishii was over one hundred years old when he died on September 18, 1936. He was the last surviving member of the gannenmono.

For the Hawaiian Monarch, King Kalakaua, Sentaro Ishii and other gannenmono would become the living testament of the positive feeling he had for the Japanese. They were individuals who chose to work, who chose to stay, and who chose to cast their lot together with the people of Hawaii. He recognized and expressed openly to the highest officials in Japan his desire to have more Japanese come to the islands.

Because of his efforts, many Issei came to Hawaii between 1885-1924. Feeling close to the people of Japan, when the first group of immigrants arrived from Japan aboard the City of Tokio on February 8, 1885, King Kalakaua was at dockside to welcome them to his Kingdom.

Most were young, healthy male laborers who wanted to earn money to send back to their families. But conditions proved to be difficult working on the island sugar plantations. Of about 180,000 who came between 1885 and 1924, the majority returned to Japan.

The history of Hawaii Japanese is about the Issei who chose to stay. They numbered about 39,000. Though fraught with challenges, it was a decision they would not regret. Issei life was difficult—Japanese immigrants faced anti-Japanese sentiments, unfair racial practices, and harsh working conditions. However, instead of viewing themselves as sojourners or temporary workers who must simply endure such hardship, they envisioned themselves, like the gannenmono before them, as individuals who would cast their lot together with the people of Hawaii and build a better future for families and succeeding generations. Instead of bowing to the pressures of plantation life and unjust treatment, they took a dedicated, long-term view of their chances in Hawaii.

From 1907-1923, wives and picture brides traveled across the Pacific Ocean to meet their husbands on a new shore. They started families, and by 1915, 46% of the babies born in Hawaii were of Japanese ancestry. That birth rate rose to more than 51% in 1923, which is to say, every other baby born in the islands was Japanese. The growth of families provided a stabilizing influence, and the Issei community began to flourish.

Many did not stay on the sugar plantation. In 1900, over 70 percent of the plantation workers were Japanese but by the 1930’s only about 20 percent. Some Issei became fishermen. Others raised Kona Coffee. A few were hired by rich white families and became domestic servants and gardeners. With the help of friends and the practice of tanomoshi, or mutual lending, certain individuals were able to open stores or start a business.

Most Issei had moved into Honolulu and other island towns. All worked hard and maintained a frugal way of living. With the greater part of their life ahead of them, they found work in many difference occupations:

| DISTRIBUTION OF JAPANESE BY OCCUPATION - 1930 | |||

| Occupation | Males | Females | Total |

| Sugar Plantations | 6,664 | 567 | 7,231 |

| Pineapple | 2,511 | 579 | 3,090 |

| Rice Cultivation | 131 | 28 | 159 |

| Coffee Cultivation | 828 | 298 | 1,126 |

| Vegetable Truck Farming | 998 | 259 | 1,257 |

| Horticulture | 208 | 60 | 268 |

| Dairy/Piggeries/Poultry Raising | 814 | 144 | 958 |

| Various Agriculture | 1,331 | 371 | 1,702 |

| Domestic Servants | 1,285 | 1,599 | 2,884 |

| Agricultural Laborers, misc. | 1,671 | 286 | 1,957 |

| Day Laborers | 968 | 125 | 1,093 |

| Fishing | 969 | 5 | 974 |

| Laundry Workers | 249 | 371 | 620 |

| Food Manufacture & Procesing | 149 | 58 | 207 |

| Confectioners and Bakers | 39 | 5 | 44 |

| Misc. Manufacturing | 525 | 16 | 541 |

| Tailors/Seamstresses | 195 | 672 | 867 |

| Construction Contractors/Carpenters Masons/Painters/Plumbers |

4,416 | 1 | 4,417 |

| Auto Repair | 461 | 6 | 467 |

| Retail/Drugstores/Drygoods/Clothing/ Cooks/Jewelry, misc. |

2,139 | 370 | 2,509 |

| Elecricians/Surveyors/Draftsmen/ Engineers |

230 | — | 230 |

| Hotel/Inns/Boarding Houses/Barbers | 414 | 381 | 795 |

| Restaurants/Pool Houses/Entertainers | 247 | 99 | 346 |

| Railroad/Auto Drivers/Freighters | 1,665 | — | 1,665 |

| Artists/Photographers/Musicians | 104 | 8 | 112 |

| Nurses/Midwives/Masseurs | 67 | 193 | 260 |

| Reporters/Insurance Salesmen | 114 | — | 114 |

| Buddhist & Shinto Priests | 146 | 7 | 153 |

| Christian Workers | 27 | 4 | 31 |

| Office Workers/Bank Clerks, etc. | 3,374 | 479 | 3,853 |

| Educators | 336 | 455 | 791 |

| Doctors | 60 | — | 60 |

| Dentist | 46 | — | 46 |

| Pharmacists | 35 | — | 35 |

| Legal/Attorneys | 23 | — | 24 |

| Government Workers | 135 | 3 | 138 |

| Others | 3,159 | 575 | 3,734 |

TOTAL |

36,733 |

8,025 |

44,758 |

| Source: Kihara,Ryūkichi. Hawaii Nihonjinshi (A History of Japanese in Hawaii). Tokyo: Bensei-sha, 1935. |

Indeed, 1930’s mark a significant period in the lives of the Issei. For many, it was the decade that Issei became an integral part of Hawaii’s community. In the business sector, they opened laundries, cotton factories, sake breweries, family restaurants, and bakeries. They started poultry, hog, fish, vegetable, fruit, and flower farms, among other establishments. They became significant members in skilled trades. They were Hawaii’s carpenters, plumbers, electricians, mechanics, and contractors.

With the rise of Issei in business, the 1930’s also marked the rise of Japanese community institutions. Language schools, religious temples, and churches were established. Social, professional, and civic organizations formed. Time devoted to leisure activities, sports, and community celebrations became more a part of the Issei’s activities and family life. The world of friendship and sense of community expanded and grew. Issei family businesses, husbands, wives, and children, served the diverse needs of Hawaii’s multi-ethnic and inter-racial communities. Customers became friends and long term relationships were established. Japanese, Chinese, Filipino, Hawaiian, and Haole families enjoyed attending community sports and leisure events together.

Leisure Time Activities and Sports

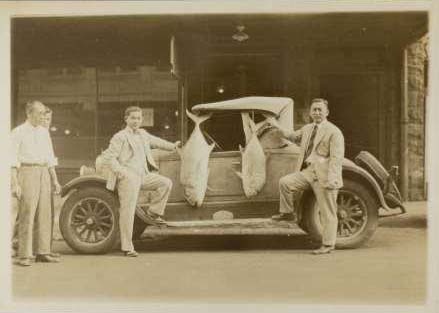

Whether through fishing, sports, or martial arts, Issei became active participants in leisure time activities that would characterize their Japanese community and island lifestyle.

Family Stores

Issei families established stores in Honolulu and other towns to serve the diverse needs of the community.

Community Celebrations

Issei families with their children, the Hawaii born generation, held public celebrations, and supported Japanese commemorative events.

The emerging Issei community became an integral part of Hawaii’s make up. For the Issei, though they ceased living in Japan, they never ceased being Japanese. They loved Japan and they loved Hawaii, too. To love Japan did not require the exclusion of their love for Hawaii, or vice versa. The Issei were proud of their unique identities as Hawaii Japanese Americans because Hawaii, with the community they had built, was their home. The Issei would never hesitate to tell their children, “Lucky Come Hawaii.”

This year, 2018, marks the 150th year of Japanese in Hawaii. From the gannenmono arriving in 1868, King Kalakaua’s positive feelings for the Japanese and Issei story, it is a history we honor.

It is a history that has shaped the Hawaii we know today.

* This article includes excerpts from the upcoming book Who you? Hawaii Issei (Hawaii: University of Hawaii Press, May 2018) by Dennis M. Ogawa and Christine Kitano.

© 2018 Dennis M. Ogawa and Christine Kitano