“I grew up thinking women were stronger than men in terms of the absence of anger and self-pity. Absence of bitterness.”

– Paul Takemoto

If you ever have the pleasure of meeting Alice and Paul Takemoto, you will be in the presence of an endearing mother and son relationship. Sitting with them felt like a reunion with old friends, full of unexplainable but palpable comfort. Alice has a voice so sweet, she could deliver bad news and you’d receive it warmly. And when Paul cracks a joke (which is frequently), Alice’s laugh is infectious.

As star subjects in the documentary Relocation, Arkansas by Vivienne Schiffer, their family history comes to light in the backdrop of the camps at Jerome and Rohwer, paralleled with the story of the South’s bumpy road to desegregation. Now 91 years old and the youngest of four girls, Alice was a teenager when the war broke out, uprooted from her family’s stable and comfortable life in Los Angeles.

Her husband and Paul’s father, Kaname Takemoto, experienced a starkly different WWII as a combat medic in the 442nd, which did not come without its consequences. “In retrospect, he clearly had undiagnosed, untreated post-traumatic stress disorder,” says Paul. “They were just all screwed up.”

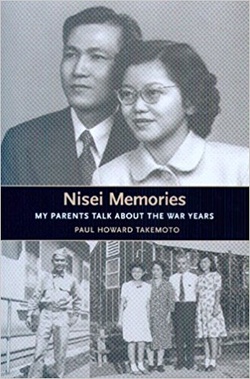

But despite a tumultuous experience, the Takemotos have thrived. To say they are an accomplished family puts it mildly: Alice is a classical pianist who still plays chamber music, and Paul has been a spokesperson for the Federal Aviation Administration for over twenty years. He also wrote a book about his parents called Nisei Memories: My Parents Talk about the War Years.

Alice began our interview by telling me that both of her parents, Zenichi and Yoshiko Imamoto, were imprisoned a few months after Pearl Harbor on account of them being Japanese language teachers in a tiny Southern California town.

Where was your family living before the war?

Alice Takemoto (AT): Norwalk, California, which is right near Disneyland. It’s in L.A. county but at that time it was kind of a crossroads where you rolled up the window because there were all these dairy farms. But there was a Japanese school, quite a large one. My father was the principal.

Paul Takemoto (PT): It’s still there.

AT: It’s still a very thriving cultural community with not only Japanese but other Caucasians. They’ve got judo–

PT: Kendo classes, basketball, and yeah, it’s amazing.

That’s amazing. That must bring you comfort that something your parents were part of is still there.

AT: Well it’s the strangest thing because that the community center is thriving, but they have no record of my father or mother being the teacher there.

Do you think that had something to do with the FBI records? Or that it was just so far back?

AT: I don’t know. My father was there, let’s see. I was in the seventh grade and we left when I was a junior in high school. He was there enough years.

Were you the eldest in the family?

AT: I’m the youngest of four girls.

So they were teaching, and Pearl Harbor happened. Were they picked up immediately?

AT: Actually you know, all the schoolteachers were picked up on the same day, which was March the 13th. And Buddhist priests and ministers. First group were all the business people. And that was really on Pearl Harbor day.

When they were taken, what happened to you and your sisters?

AT: Well my oldest sister was going to UC Berkeley. And my next sister was going to nursing school either in Oakland or I don’t know where, but they were close. And my next sister was 18 and she was going to community college, and I was 15 in high school. So, when Mother and Father were taken, it was just the two of us minors left alone. And they wanted to send a police matron and we said we didn’t want any strangers. Have you heard of Terminal Island?

Yes.

AT: Well those people were fishermen and within 24 or 48 hours they had to leave the island so the different churches had them go different places. And we had about 65 of them living in our school-house. We didn’t know them but they were right next door, so my sister and I said we didn’t feel that alone. But they didn’t know us and they didn’t know that my parents were gone – there was no connection.

PT: Were they families?

AT: They were families. And they went to our high school for that duration. They came – I can’t recall when they came, might have been February. I think they walked with me to the bus stop. I blocked all that out or just don’t know. But my sisters had to come home when the curfew was instated. So Mary and I were alone for two weeks and then they came back. And then two weeks later, we were in Santa Anita. So we were one of the early ones to go. We were April 13, just a month after Mother and Father were taken.

AT: So there were five big mess halls, like 5,000 people ate at each one of them. We were the first ones out, our family number was 2138, so that’s pretty low. And the mess hall didn’t know how to cook. The evacuees had to do all the work. It was really – it was really a mess.

Did you know where your parents were? Could you communicate with them?

AT: Well certainly, the officials don’t let you know. So by word of mouth, I don’t know who told us but my father was in, they call it Tuna Canyon, we called it Tujunga near Hollywood Hills. And there, we could talk through a fence, nobody was listening to us. But with my mother, that was a federal prison. So there’s somebody listening, right in the room with you. And all you could do is just cry. That was really hard, and she had a miserable time.

PT: Wasn’t she in the L.A county jail first?

AT: They were put in the county jail. Mother and Father never talked to us about it for the longest time until I had to probe. See, Father had gone to another city to take care of a family where they had dual citizenship, so he was out of town. So when the FBI came, they took Mother, and then Father came home and they took him but neither of them knew the other one was arrested.

AT: So they all went through the county jail system and Mother was in a cell with two other people. I know she told me they took her belt, anything like that, and they were put in a cell. I’m not sure how long they were held there. But any criminal would go through that same kind of stuff. Then she was sent to Terminal Island for two or three months, then they have a hearing and they have witnesses. There was a Caucasian Quaker minister—Nicholson—who spoke Japanese. So he was asked to be a translator at Mother’s hearing as well as another Issei lady. And so she passed her hearing, and then after three months she came to join us in Santa Anita.

Father, his hearing, I don’t know whether he had any Japanese witnesses or not but we have this paper where there were three people who were on the board and they voted to let him go free. But the Attorney General Biddle nixed it, so Father was sent to where he was a prisoner of war. And then the other thing that I’ll never forget, is that I just wanted to know why they were arrested because Father was not an activist in any way. He certainly did not – I didn’t get any propaganda at that time. Anyway, later on I asked my ex son-in-law who was a lawyer to write a letter to the FBI with the Freedom of Information Act. And I got about ten pages blacked out and at the end it says, ‘There is no indication that your parents were ever arrested.’ And you know, that’s really cruel.

So they just tried to erase the record?

AT: Oh it was all blacked out, whatever they printed out. But at the end, the type was saying there was no evidence. I don’t know how they did that.

So then your mother came to Santa Anita, and you and your sisters were there as well. So their education at CAL and nursing school was all interrupted?

AT: Right. My sister said people who had midterms did graduate. She was a senior but she didn’t get her diploma. So she put her education on hold and she went with me to Oberlin, three semesters because I was only 16, coming directly from camp. So she went and she worked in this graduate house where they had dinners for faculty, and she was the assistant cook. But that’s what she did for me.

PT: She’s great, my Auntie Grace.

And she’s still alive?

PT: They’re all alive. They’re all in their nineties. They’re all still with it, too. Her mom lived until 105. And feisty the whole way.

AT: I have to tell you about it. See I’m 91, Mary turned 94, Lily’s going to be 97, and Grace is going to be 98 in January. And nobody has depression, nobody has dementia. Just forgetfulness.

In what way? Because I love that you just said none of you had depression. You have such a good spirit.

AT: I think it comes from my mother. Paul’s son just went to Japan and wanted to find relatives and he went to the house that my mother was born in, and it’s a big house. And she came to this country, married my father who was a schoolteacher, and every house was a very modest house. I thought they were nice homes. But they were all smaller houses. And then I think about Mother going to prison, and then working as a domestic. She never, ever, ever talked about her past life that was rather luxurious. Never talked about that.

PT: She was amazing. Strongest person I ever knew. No pity, no bitterness. All forward.

AT: And kind of frank, too. I have to tell you this story. At her 105th birthday we went to her nursing home. And the family was decorating. And she and I were sitting out in the garden and I was wearing a jumper and I said, ‘Mom, these threads I dyed, I threaded the loom and I wove this fabric and then I cut this jumper and sewed it. She said, ‘It’s a little big under the arm hole.’ [laughs] She was a pistol, you know?

PT: I was in college, and she told my mom that it was okay if my older sister married someone who wasn’t Japanese but she wanted me to marry someone who was Japanese. This is in Kensington, Maryland. So I wrote her back and said, ‘Grandma, there are two Japanese girls I wouldn’t mind going out with but the one doesn’t know I’m alive and the other doesn’t want anything to do with me. We’re going to have to expand the pool if you want me to get married.’ She wrote me back a cute letter, she laughed and she sent me $20 to buy new jeans because she didn’t like my jeans. She was a pisser.

AT: She was a schoolteacher, so she did not have buddies amongst the parents. She did not allow that. And that’s smart, too.

So that she wouldn’t play favorites with the kids?

AT: No, I think there could be petty gossip in this Japanese small community. But I do remember I learned how to drive when I was ten because in the schoolyard I couldn’t hit anything. I remember driving my mother at nighttime to see this one friend and I would sit there with the daughter. And Mother would listen to the mother, and the other mother’s crying. But that’s the only family she would go to visit. And later on I find out that this family was another class, there was inter-marrying there. I think there was abuse to the woman by the husband to this woman’s daughter. You know the word kobosu, meaning to cry, to shed tears? So Mother was a listener. I heard from my sisters, like, thirty years later. But she did that.

She was very strong and could give that comfort.

PT: She was my hero.

AT: In our community of Japanese, there were these class structures from Japan. And I didn’t know anything about it, my sisters knew nothing about this because my parents wouldn’t discuss it. Other people would tell my sisters and then later on I would hear ‘this person married this person,’ and they were never talked to after that. So all of this gossip I’m hearing when I’m 60 years old when everybody’s already gone, but that kind of thing goes on in any kind of community. My mother and father never ever told us anything like that.

So you got a sense of what they went through because of your sisters or did you ever ask your mother and father about it?

AT: Well, the first time I went to the archives, I went with Min Yasui’s sister. She said, ‘Ask your mother, get the information.’ So I called her on the phone the next day, and Mother said, ‘Why are you asking these things? It’s ancient history.’ So she didn’t want to talk about it. And when I’d go to visit her, she’d always talked about this other lady who was this minister’s wife who was arrested too, with Mother. Mother was released after her hearing, but this other lady Mrs. Wada, went to federal prison for two more years.

It was such overkill.

Did you know that these ships with Japanese sailors would come into San Pedro? And as soon as you step on the boat, there’s a little thing with water where you have to disinfect your hands. So who knows? [laughs] I don’t know anymore than that, whether Mother’s uncle was on that ship. I have no idea.

PT: Wait, so Grandma’s uncle was an admiral in the Japanese navy?

AT: Yes. Grace told me that.

After a side about trying to get the details of the admiral, Alice transitions to talking about her grandfather in Japan.

AT: Miyaji is a little village, it still is a little village. He was the mayor of the village but something had happened concerning money and it wasn’t my grandfather’s fault but he attempted the sword [Alice motions seppuku] and failed. This is what my oldest sister says, that she remembers my mother crying.

PT: Well then he jumped in front of a train.

AT: Then he succeeded. He threw himself in front of a train. She never saw her parents once she left there. She went back after my father died at age 81, and at that time it was the 25th year since her mother died and the 50th year since her father died. And the temple was right next door where they had the services, she said she just cried all day. But when you think she never told–I never knew anything about this–I never knew. I heard it from my sister.

Did your mother tell your sister?

AT: She said Mother cried.

PT: Auntie Grace remembers Grandma crying?

AT: Yeah, she does, she does. So if Mother was 80, it would be fifty years, so she must’ve been 30 years old when her father died. She went through a lot but she was always very thankful for what she had, which to me is amazing. I think about her a lot. I went to that house and I was just marveled that it was an old house but it had features like the shoji screen that you put your finger in and it was cloissoné. At that time it was 150 years old.

To be continued ...

* This article was originally published on Tessaku on December 16, 2017.

© 2017 Emiko Tsuchida