One intriguing aspect of Japanese immigrant experience before World War II was the diverse intellectual life of community members. Although most early Issei were farmers or laborers, a significant group of writers and thinkers emerged among them. These people found work as Buddhist priests, school teachers, or newspaper editors within Japanese communities.

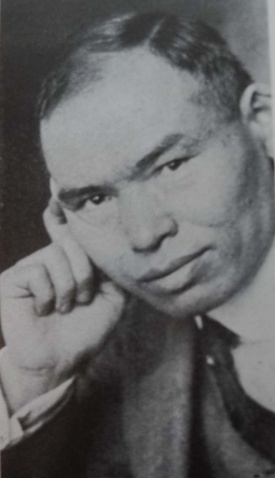

As Eiichiro Azuma shows, they wrote primarily in Japanese, identified with the old country, and were heavily invested in building a “shin nippon,” a new Japan in the New World. Yet overlapping with them was a selection of students, artists, and professionals who might be termed “cosmopolitan Issei”. They generally lived outside ethnic communities, developed primary contacts with whites, and willingly absorbed themselves in Western culture. Unlike the majority of Issei, they wrote in English, producing novels, poems, and plays, as well as non-fiction. This audacious move symbolized their quest for a diverse readership and their demand for recognition as equal players in conversations about America. Perhaps the most notable representative of the “cosmopolitans” is K. K. [Kiyoshi Karl] Kawakami.

During the prewar decades Kawakami produced numerous books and articles in English, plus a pair of books in French. These works reflected the odd evolution of Kawakami’s career. At first critical of Japan and its “feudal” society, he later became an influential apologist for Japanese imperialism, then still later turned against Tokyo and supported the United States during World War II.

Kawakami was born in Japan in 1873 (according to one source, his birth name was Yūshichi Miyashita). Orphaned at an early age, he nonetheless was able to attend school and learn English. After moving to Tokyo at age 17, he enrolled in legal studies, then attended Aoyama Gakuin, a Methodist school where he presumably learned English.

Kawakami converted to Christian socialism, and he became one of the founding members of the Shakai Shugi Kenkyukai (the Society for the Study of Socialism) and the Shakai Minshūtō (the Socialist Democratic Party) alongside the better-known socialists Abe Isoo, Katayama Sen, and Shūsui Kōtoku. Inspired by Karl Marx, Kawakami took the English name “Karl” and thereafter referred to himself as Kiyoshi Karl (K. K.) Kawakami.

Following the collapse of Japan’s first socialist party in 1901, Kawakami left for the United States, where he attended the State University of Iowa to study political science. His master’s thesis was published in English as The Political Ideas of Modern Japan by the University Press (Iowa) and the Japanese firm Shokwabo, both in 1903. After receiving his masters degree from Iowa, Kawakami attended the University of Wisconsin to continue his studies, but did not finish. Instead, he helped found the Seattle Japanese Socialist Party with Katayama and worked for the Japanese Commission at the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition held in St. Louis.

During this time, he also worked as a foreign correspondent for the Japanese newspaper Yorozu chōhō, which had begun to publish his writings during his Tokyo days. In 1905, Kawakami traveled to New Hampshire to cover the Treaty of Portsmouth, which ended the Russo-Japanese War. In 1907, he married Mildred Clarke, a white woman, and moved to her hometown of Momence, Illinois, where he spent the next several years. During this time the couple had two children, Clarke and Yuri.

By this time, Kawakami had become disillusioned with socialism. Attracted by the plight of his fellow Issei, he published numerous articles defending Japanese immigrants in California as well as Japanese imperialists in Asia. Many of these articles were published in his 1912 book American-Japanese Relations, which was highly praised by the New York Times for its “everlasting righteousness and common sense.” The Times reviewer praised Kawakami’s conclusion that the Gentlemen’s Agreement would solve the immigration problem, as identical to what “scientific inquirers, the best businessmen and the statesmen, whose eyes are not on votes, have long held.”

In 1913 Kawakami moved to San Francisco (where his youngest child, Marcia, was born) to participate in the struggle against the exclusionist movement as the general secretary of the Japanese Association of America. In 1914, he became the head of the Pacific Press Bureau, established by the Japanese consulate in San Francisco to create a positive image of the Issei (in 1919 Kawakami joined forces with missionary and publicist Sidney Gulick to press for liberalized immigration policies, for which the two were publicly accused by California Senator James Phelan of being Japanese government agents).

Kawakami produced a series of books that argued for Japanese inclusion into American society. What is particularly striking about these works was Kawakami’s self-presentation. In his 1914 book, Asia at the Door, published shortly after passage of the 1913 Alien Land Act in California, Kawakami spoke as an American, not as Japanese or Japanese American. “Fate decreed that I should make my home in America and have American relatives and friends, who do not hesitate to take me into confidence and reveal to me both the lighter and darker phase of American life.” (53)

As a self-appointed insider, he undertook a frankly elitist defense of Japanese immigration. “The restriction of immigration is no doubt one of our sovereign rights, but in exercising such rights we must not single out…a civilized and progressive nation [as] the object of discrimination....It was this sense of justice which inspired our forefathers and which made our country unique and spiritually great in the concourse of nations.” (33-34, 35) A just policy towards Japanese immigrants, whom it had the responsibility to protect and uplift, was part of America’s long mission to free Japan from the legacy of its “oppressive past” and instill in its people “the idea of personal rights and freedom essential to a constitutional government.” The treatment of Japanese immigrants in America encapsulated the choice for the West between equal friendship or conflict with a rising Asian continent.

Kawakami’s position was fundamentally contradictory. He maintained that immigration should be restricted to only the better classes of immigrants from both Europe and Asia, and he was ready to concur in nativism and white supremacy as long as the Japanese were recognized as among the superiors. (146) Indeed, he asserted that it was natural for Californians to consider themselves a superior race. In the text, he speaks condescendingly of immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe, and continually contrasts the Japanese Americans with the Chinese, whom he calls variously a race of effeminate “ideal servants”(142), a criminal gang of “hatchet men,”(129) and gamblers (He reports that Sun Yat-Sen’s revolution was financed by the Chinese gambling parlors in California who profited from the Japanese trade). In fact, the only group which comes in for more scathing criticism than the Chinese in the book are the native Hawaiians, whom he calls “the offspring of animal rather than of the intellectual faculties, governed by traditional customs of a very low order.” (188).

Yet his standard of desirability was not simply racial. Kawakami insisted that “No man is worth while who does not respect himself and the race of which he is a member. Neither is he a desirable member of the democracy who cherishes prejudice against other races.”(84). Nor was it entirely social: On the one hand he decried the dishonesty and deceit of both Japanese and Americans of “a certain class.” At the same time, he deplored the influence of the Japanese consul in Hawaii and of Buddhist priests and missionaries in the islands in chiefly economic terms: the consuls for collaborating with white planters in enforcing exploitative contracts and preventing workers from migrating to the mainland, and the Buddhists for spreading narrow pro-Japanese propaganda and extorting contributions from poor parishioners. Nor was Kawakami entirely an advocate of assimilation.

To be sure, he believed that the principal point in favor of Japanese immigrants was their capacity to be quickly “Americanized” and pointed with pride to the offspring of white-Japanese intermarriages as appearing completely American (p. 73). Nevertheless, he praised Japanese schools on the West Coast and Hawaii for instilling cosmopolitan ideas in children and promoting cultural interchange. Kawakami asserted that Japanese Americans stood at the border between West and East, and their treatment, albeit a minor question in itself, symbolized the relations between the two worlds.

Kawakami’s cosmopolitan optimism was soon strained by the success of anti-Japanese legislation, including the Alien Land Act, which he termed part of a policy of “extermination.” (173). In his next book on the subject, The Real Japanese Question (1921), he bitterly denounced the politicians who were in his mind chiefly responsible for stirring up race prejudice and inspiring exclusionary legislation. The book generally rehashed the arguments Kawakami had already presented in Asia at the Door. Though his bias was if anything even sharper against Chinese than in the earlier book, he criticized American immigration law as absurd for excluding qualified Chinese and Japanese immigrants, yet allowing citizenship to undesirable non-Caucasians such as Mexicans, Hungarians, Hindus, Finns, and Persians, and Syrians. The most striking change from Asia at the Door, however, is in Kawakami’s rhetorical strategy. No longer would the author describe himself as an “American,” or assume that right-thinking people opposed restriction. Instead of speaking about the innate assimilability of the Japanese, he asked only tolerance.

Following the passage of the 1920 Alien Land Act in California, the Pacific Press Bureau was disbanded, and Kawakami and his family moved to Washington D.C. in 1922. In the following years, he primarily worked as the Washington correspondent for the Osaka Mainichi Shimbun and the Tokyo Nichi Nichi Shimbun, but also wrote regularly as a freelancer for such magazines as Japan: Overseas Travel Magazine and Japanese Student, as well as producing various books, such as a biography of chemist Jokichi Takamine. In 1937 he travelled to Italy as a representative of Japanese newspapers, and interviewed Italian dictator Benito Mussolini.

During these years, Kawakami became known for championing Japan’s foreign policy, including the Japanese occupation of Manchuria. Although Kawakami briefly criticized the decision of Japanese policy makers to sign the Anti-Comintern Pact with Nazi Germany in 1936, he continued to defend Japan’s actions in Asia. After Japan invaded China in 1937, Kawakami attempted to convince his American readers that Japan was fighting a war to secure American, British and Japanese commercial interests in China against the Soviet-led Communists. As late as summer 1940, he published an article in Foreign Affairs portraying Japan’s actions in China as an effort to enforce the Open Door Policy. He stopped defending the Japanese government after it signed the Tripartite Pact with Germany and Italy in September 1940, arguing that Japan was “devoid of a forceful leadership.”

Despite the change of position, because he was best known as the leading prewar defender of Japanese foreign policy, Kawakami was apprehended as enemy alien on December 8, 1941, the day after Japan bombed Pearl Harbor. He was taken to Immigration Center at Gloucester City, New Jersey, where he remained detained for several weeks waiting to appear before the Enemy Alien Hearing Board at Fort Howard, Maryland.

During this time, he received important support from several prominent Americans, including Felix Morley, the president of Haverford College who had known Kawakami when he served as the editor of Washington Post, a newspaper that regularly published Kawakami’s articles on Japan’s foreign policy during the previous decade. On February 11, 1942, Kawakami was paroled after hearing by order of Attorney General Francis Biddle. He spent most of the war years in Washington. Towards the end of the war, he began publishing occasional articles on Japan for the Evening Star newspaper. Meanwhile, his son Clarke joined the U. S. Army as a Japanese specialist.

Towards the end of World War II, Kawakami reemerged in public, continuing his argument from the 1930s that the United States and Japan must cooperate to fight the Communist threat. Many of these writings were published in Human Events, a conservative anti-communist magazine. Kawakami passed away on October 12, 1949 in Washington D.C.

© 2018 Greg Robinson and Chris Suh