Artist Erica Kaminishi, born and raised in Mato Gross, Brazil, is one of the hundreds of thousands of Nikkei Brazilian dekasegi who have migrated to Japan to work or study, a hundred years after their ancestors immigrated. Over a span of ten years, she worked, studied pottery, and attended a PhD program in Japan. She now lives and works full-time as an artist in Paris, France, but her roots as a Nikkei Brazilian and her time in Japan have clearly had an impact on the way she sees and thinks.

Kaminishi is one of thirteen artists selected to participate in Transpacific Borderlands: The Art of Japanese Diaspora in Lima, Los Angeles, Mexico City, and São Paulo. The question of Nikkei-Latin American identity was a critical point in the selection of the artists. Michiko Okano, who curated the Brazilian Nikkei section of the exhibition, says, “It’s important to understand the diversity of the artists and to verify that different sensibilities are developed depending on several factors—the singularities of each artist, their artistic experiences, and their life experiences.”

Curator Okano included two pieces of Kaminishi’s: one, a series of text-based topographies of sorts, soft curves that rise from the paper, embellished with the poetry of celebrated poet Fernando Pessoa, that is painstakingly rendered by hand in Kaminishi’s tiny script in jewel tones, and two, an installation that immerses the visitor in a wash of emotions. Since the show opened in October, I have seen numerous photos of the spectacle she had created within the gallery—a room hung with 3,300 transparent petri dishes filled with 60,000 synthetic, pale pink blossoms, meant to emulate the effect of walking beneath a blossoming cherry tree. Kaminishi’s large-scale installation, Prunusplastus (2017), is something of a visual wonderland, and yet the meditation on its message is really curious. “Prunus serrulata” is the Latin name for the Japanese cherry, while “plastus” is Latin for “something modeled.” According to Kaminishi, the piece conceptualizes the nature of one’s cultural DNA through this quasi-scientific lens. “In Japan, the celebration of flowers blooming in the springtime, such as the famous cherry blossoms (sakura), is a major tradition. I wanted to reproduce this atmosphere in a contemporary way, while examining the ways that we appreciate and nurture culture…The work touches on the Japanese concept of ‘mono no aware,’ which holds that while beauty is very affecting, it is also, like all things, ephemeral. Nothing is eternal.”

The following email interview with Kaminishi is just the beginning of an inquiry on the role of art interpreting Japanese migrant history and culture. It left me open to reimagining my own approach to words, symbols, and identity. Nikkei culture is embedded within us. Nikkei culture is artificial. Nikkei culture is an illusion, a memory—maybe even just an inherited memory that has been described in a household object, in language, or a distant song.

* * * * *

Patricia Wakida: Tell me about your family’s history, or what you know. Where are your ancestors from originally? Where did they settle? Do you think there were particular experiences that had a big impact on their personal history?

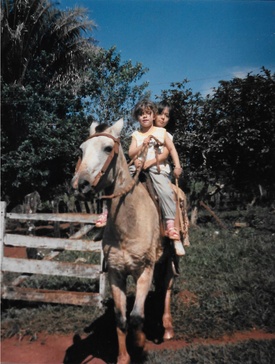

Erica Kaminishi: Both my maternal and paternal grandparents are from Miyagi province in northern Japan. My maternal grandparents migrated to Brazil with my aunts, who were still small children. They first settled in the countryside of São Paulo, like most of the Japanese immigrants in Brazil. Later, they moved to Assaí (which is derived from the Japanese city of “Asahi”), which is a village in the northern state of Paraná, where the majority of the population is of Japanese descent. There were several established Nikkei communities in this region and my grandparents ended up working on coffee and cotton farms. They had thirteen children.

My paternal grandparents met in Brazil. My grandmother came with her older brothers, although perhaps she was “forced” to emigrate since only families were allowed to travel. The siblings settled in the rural interior of São Paulo, where my grandmother was introduced to her husband through miai, or an arranged marriage, which was customary for most Japanese immigrants. After they were married, my grandparents moved to a rural community (Cabiuna) in Assaí, where they bought a small farm.

My father didn’t share many stories about his family, perhaps because my grandfather died when my father was only 12 years old. But I do know that my grandfather immigrated with his brother (my great-uncle) and mother (my great-grandmother). The boys were the two youngest children, and had no right to inheritance, which is reserved for the eldest son (chonan). Their only possession was their grandfather’s (my great-great-grandfather’s) samurai armor, which they had to sell to pay for their trip. According to my father, his great-grandfather immigrated to the Miyagi region right after the end of the castes brought about by the Meiji revolution. He bought large portions of land and the family became quite wealthy. I also know that my grandfather was the most artistically talented member of the family; he painted, played the shakuhachi and practiced calligraphy (shodo). If I’m not mistaken, my great-uncle’s family in Miyagi, Japan still owned some of my grandfather’s paintings until recently, but the 2008 earthquake destroyed everything. One of my father’s early childhood memories in Brazil are of my grandfather painting at home on rainy days, when he couldn’t work outdoors. When my grandfather died, my grandmother, maybe because of a stressful momentary situation, burned all his paintings.

I believe that coming to Brazil and the premature death of my grandfather were the two experiences that impacted our family history. Neither my grandfather nor my father had the opportunity to develop their artistic skills. My father had to start working very early in life and he could not continue his studies, but he was always a fine craftsman. Even now, he creates objects and wooden toys using recycled materials. Maybe I inherited these artistic instincts from them.

I understand that your parents eat Japanese food at home, are Buddhist, and speak a mixture of Portuguese and Japanese to the children. Tell me more about the larger community where you grew up. Was your family part of a Nikkei Brazilian community? What was that like, from your perspective?

As children and as young adults, we accept that the family culture that we are raised in as perfectly natural. It’s like living in some sort of time capsule. The issues of being Nikkei in Brazil only became relevant to my immediate family when my parents went to Japan to work, and later when I also went to Japan and suddenly realized that the real Japan was not like the Japan of my childhood home.

My parents spent most of their lives in closed communities in the countryside of Paraná. In Assaí, the town where they grew up, there are several rural communities divided into distinct sections:

Cabiúna, Seção Palmital, etc. Even today, those communities are active and to visit them is like going back to the past. Every Nikkei house there keeps souvenirs from Japan in them such as pictures of a member of the royal family, and there’s always the smell of incense in the air since the Buddhist altar still holds a privileged place in the house.

It is the contrast with the environment outside that takes you to the Japanese culture, a place made of memories and the tropical landscape of rural Brazil with its very red soil. My mother learned Portuguese only after she got married and moved to the city. She still uses words that only exist in the Nikkei culture, even though she lived in Japan for a long time during the 1990s. For example, she uses terms such as yo-ra (yo meaning “me”, in one of the oldest and most formal forms of Japanese language) and você-ra (você is Portuguese for “you”). She uses the word kimono for clothes, and ofuro for the bath. My parents still observe traditions such as preparing certain dishes like sekihan on special occasions. To this day, my parents make their own tofu, tsukemono, and dashi at home and until recently, once a year a Buddhist monk would come to our house to pray at our family altar.

It is interesting and funny in some ways, but it shows how the Nikkei of their generation has kept our ancestral culture alive, a rural Japanese culture that no longer exists in contemporary Japan. From my point of view, these are all inherited traditions that have been handed down. My parents didn’t get to know Japan until they moved there, when they were almost 50 years old, and some of my uncles and aunts still have never visited the country. Their culture is a legacy, of an imaginary Japan.

You’ve had a variety of life experiences, including living in Japan as a dekasegi, working at a phone company. First, why did you decide to go to Japan?

I had just finished high school and was accepted to study history at the University of Londrina, Paraná. My parents had returned to Brazil after working as dekasegi in Japan for a few years and my older sister, who went with them, was also back in Brazil but wanted to go back and do her studies in Japan.

She wanted to try studying at a Japanese university. I decided to join her because she had lived and studied in Tokyo and she knew people there who might help us. I had another sister, our eldest sister, who was married and living and working in Japan too. So in a way, I was under the tutelage of my sisters, as it has always been since I was ten years old, when my parents first went to Japan and I stayed here (in Brazil) to continue my studies.

In the beginning, Japan was very difficult. I worked numerous jobs and worked in many different environments. During my last year in Japan, I stopped studying Japanese once I realized that the Brazilian curriculum could not be applied to a Japanese college. So I decided to study art on my own. I took a course in ceramics and then with my own savings, I went to London to study English and to get to know the local culture. I understand that I needed a basic arts education and skills, and the arts and culture are generally very Eurocentric, which is why I chose London.

Was that your first time to Japan? What was the work like? Did you find community in Japan? Did you meet any family?

Yes, it was my first time. At that time, now 20 years ago, there were different job levels for dekasegi, ranging from assembly line factory work to office tasks—usually concentrated around Tokyo. My last jobs in that time period were for Brazilian telephone companies, with a very international staff of Chinese, Filipinos, and Brazilian people all working together. I worked at the Call Center, a Portuguese answering service. I would study in the morning and afternoon and then work at night, as clients came home from work and called the company. I made good friends this way, that I keep to this day. During my last year in Japan, my mother joined me. My family is constantly coming and going, and even today I feel we have a certain urge to move and change.

Perhaps because we had foreigners amongst our family and friends, or maybe because most Japanese at this age are in college, I did not have many Japanese friends. It’s also quite interesting that I had more contact with young Japanese people when I lived in London.

Do you have a specific story to share that describes that experience?

Being born and educated in Brazil, I’ve always found Japanese social codes hard to “decipher”…I’ve learned how to observe and make mistakes until I understood how to socially behave properly, although I suppose that I will never be able to fully understand the nuances of a pause, a silence, the body language. I don’t remember any one specific story about my experience of being Nikkei in Japan, but will always remember the “scoldings” of my teachers or of a Japanese elder telling me that I should not say this or that, or telling me that I had behaved inappropriately…

* * * * *

Transpacific Borderlands: The Art of Japanese Diaspora in Lima, Los Angeles, Mexico City, and São Paulo

September 17, 2017 – February 25, 2018

Japanese American National Museum, Los Angeles, California

This exhibition examines the experiences of artists of Japanese ancestry born, raised, or living in either Latin America or predominantly Latin American neighborhoods of Southern California.

© 2018 Patricia Wakida