According to The Encyclopedia of Chicago, Chicago “has been and remains a world-class religious center with global influence.”1 Beginning in the mid-19th century, Japan was one of the foreign countries on which Chicago had a strong impact on, in the form of modern education.

Female Missionaries from Illinois and Women’s Education in Japan

When the Meiji era began in Japan in 1868, Japanese elites with overseas experience understood the necessity of educating women to strengthen the nation. Despite their awareness, the new Meiji educational system, which started in 1872, emphasized and promoted education for boys only. In order to remedy this gender gap in education, female missionaries were expected to play a significant role in promoting modern education for Japanese women. They started mission schools for girls, where they taught not only English but also western knowledge and Christianity.

Many Illinoisans participated in educating the Japanese, including missionaries who were graduates of theological seminaries in Chicago, as well as female missionaries supported by the Woman’s Board of Missions of the Interior in Chicago (WBMI) and the Woman’s Presbyterian Board of Missions of the Northwest in Chicago (WPBM). For example, Kobe Home, later Kobe College of today, and Glory Kindergarten, today’s Glory Women’s College in Kobe, were established by female missionaries sent by WBMI, in 1873 and 1889 respectively. Doshisha University in Kyoto was established in 1875 by Reverend Niijima with the help of Reverend Jerome Dean Davis, a graduate of the Chicago Theological Seminary in 1869. His Illinoisan wife, Sophia, started the Doshisha Girls School in 1876.

Additionally, the first female Japanese students at Northwestern University and the University of Chicago were graduates of Kobe Home. Shizu Mori enrolled in the College of Liberal Arts at Northwestern University in 18912 and Fuji Koga was a student in the Department of Education at the University of Chicago in 1905.3

After finishing four-terms as Mayor of Chicago, Carter H. Harrison visited Japan for a six-month stay. When he came to Osaka, he visited a girls’ school, Baika, which had been started in 1878 by Paul Sawayama. Sawayama had the distinction of being the first Japanese student to attend Northwestern University preparatory school in 1872. Sawayama had studied under Reverend Daniel Crosby Greene in Kobe who had been in the same class with Reverend Jerome Davis at Chicago Theological Seminary. Mayor Harrison visited Baika because Miss Mary Poole, daughter of William Frederick Poole, his family friend and Librarian at the Chicago Public Library, was teaching at Baika. She had been sent by the WBMI from Evanston to Osaka in 1887.

In his book A Race with the Sun, Mayor Harrison expressed his surprise at the progress of Japanese girls as follows: “fathers who, up to ten years ago, thought woman was intended to be the slave, or, at best, but the agreeable upper servant, of her father, brother, or husband, are now straining every nerve to give their daughters a liberal education, and particularly desire them to be able to read English literature, while even husbands are sending their young wives to school. “4

Female Medical Missionaries and Japanese Women

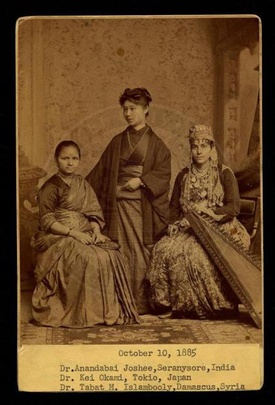

In the 1880s, the American Women’s Boards of Foreign Missions were very ambitious about medical missions by women for women. Medical activities were directly connected with charity enterprises for the poor, especially in Asia, where people often thought that the cause of disease was a superstitiously malignant spirit sent into the individual as a punishment for his or her sins.5 The WPBM in Philadelphia maintained contact with the Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania since its inception and established a scholarship program in 1881 to train female medical missionaries. A Japanese woman, Kei Okami, was awarded the scholarship in 1884 and became the first Japanese woman educated in a foreign medical school.

In 19th century Japan, prejudice against female doctors was extremely strong. Until July 1884, women were not able to go to medical schools or take exams to be doctors. Women had to graduate from medical school in a foreign country, which exempted them from having to pass exams in Japan. Furthermore, Japanese society had a long history of strong prejudice against foreigners and Christians.

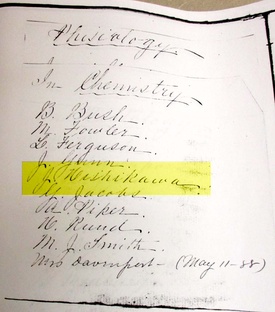

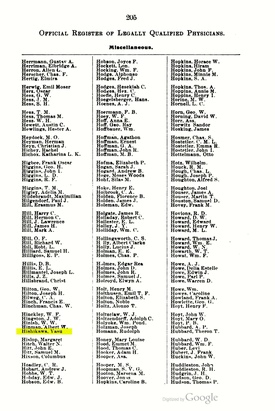

As a result of the restrictive environment in Japan, three young women came to Chicago to study medicine in the late 19th century. Yasu Hishikawa enrolled at the Woman’s Medical College of Chicago in 1886. She became the first Japanese woman to earn a license to practice medicine in Illinois.6 In 1895, there were about 300 female physicians in the State of Illinois,7 but Yasu was the only Japanese among them.

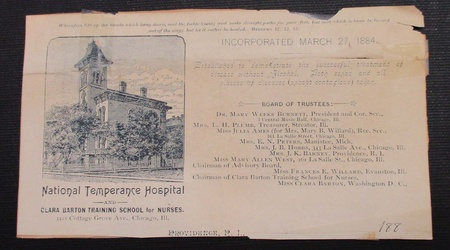

Hisa Nagano and Natsu Itoh were both once students at Doshisha Girls School before they came to Chicago in 1892 to study non-alcoholic remedies at the Clara Barton Training School for Nurses, which was part of the National Temperance Hospital of the Francis Willard’s Woman’s Christian Temperance Union.

These three women were atypical: strong Japanese women with their own free will and excellent English skills. They were greatly influenced by single American female missionaries, who had been very successful at instilling nineteenth century New England evangelical values and a strong sense of Christian social responsibility in some Japanese women.8 To these Japanese women, this sense of social responsibility outweighed the orders of their parents, husbands, and teachers, as well as the social constraints of Japanese womanhood.9

Yasu Hishikawa

In 1884, the WPBM of the Northwest and the Woman's Medical College of Chicago established a relationship similar to the one between the WPBM in Philadelphia and the Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania.

Sarah K. Cummings graduated from the Woman’s Medical College of Chicago in 1883 and was sent to Japan by the WPBM of the Northwest as the first female medical missionary. Sarah had prayed to God to send her a Japanese woman to whom she could teach medicine.10 Just before heading to the Kanazawa mission, which was founded in 1879 by Reverend Thomas Winn (an Illinoisan and a graduate of Presbyterian Theological Seminary of the Northwest in Chicago in 1874), another missionary, Mary Reade, brought her “bible woman,” Yasu Hishikawa, to meet Sarah. Coincidentally, Yasu was also praying that she could be given a chance to study medicine.11

Yasu was the first graduate of The English Speaking School for Japanese Young Ladies in Yokohama and a classmate of Kei Okami. The school was established by the interdenominational Woman’s Union Missionary Society of America for Heathen Lands in 1871.

Sarah and Yasu arrived at the Kanazawa mission in October 1883. They started a school for boys with thirty initial students in November and started a school for girls at Sunday school. Yasu helped Sarah by teaching in both schools and learned medicine through her dispensary work.

In 1884, Sarah helped to establish a scholarship program for the Woman’s Medical College of Chicago so that Yasu could study abroad. “The Grace Chandler Scholarship” was created by Mrs. Chandler of Detroit, Michigan, for the WPBM of the Northwest. This scholarship was secured through the influence of Sarah and Dr. D.W.Graham, a loyal friend of the college from the time that he came onto the faculty in 1877.12

Yasu applied for a passport with the purpose of studying medicine on April 2, 1886 and came to Chicago. She was a 25 year-old single woman, and belonged to the Third Presbyterian Church in Chicago, the same church Sarah that had been a member of.13 Starting in September 1889, Yasu was a student in Chicago for the next three years.14

One document I came across described her as follows: “She spoke the English language well, and the clear and cultivated mind she displayed in her recitations was not only a credit to her teachers, but spoke well for the intellectual capabilities of the Japanese woman. The bravery of this little woman is almost phenomenal. She came empty handed. She pursued her medical studies with marked credit, graduating with her class as one of its best students, having passed the highest examination in Medical Jurisprudence.”15

At times, Yasu was invited to visit local churches, where she was given a chance to introduce herself, as well as Japanese life and customs, to the public. For example, the northwestern branch of the woman’s foreign missionary society met at Wesley Church in Chicago on January 14, 1887, with a large attendance. On a kind of platform stage, two young ladies, Yasu and Mrs. Van Petten, the missionary, performed a skit illustrating a missionary visit to a Japanese home. They sat on the floor, offered tea and cake, and during the interview, they rendered a song in Japanese. Yasu gave an account of her conversion to Christianity, as she stood before the ladies, transformed by the power of the Lord.16

Meanwhile, nondenominational donations continued to be sent to scholarship programs for Chicago medical colleges. For example, it was recorded that the WBMI in Chicago received “$1000 from a gentleman, for a scholarship in a Chicago Medical College, so that we may have a missionary constantly in training.”17

Yasu’s speciality was gynecology and pediatrics.18 She led a brilliant career and she appeared to be unusually quick and apt. Her charming manner and bright conversational powers soon made her a general favorite. Yasu graduated with full honors in 1889,19 but did not go back to Japan right after graduation. She lived in an institution for orphans, Foundlings Home,20 and received training as a doctor’s assistant. In addition, she pursued a partial internship at the Women’s Hospital.21

In November 1890, Yasu decided to go back to Japan as a female medical missionary. A journalist wrote of her: “She is a Presbyterian in her religious belief, but she does not go to her home under the auspices of any religious denomination preferring to be independent in the line of work she has undertaken.”22 On the night of November 20th, Dr. Charles W Earle of Chicago Medical College invited professors and students of the college for a farewell party for Yasu.23

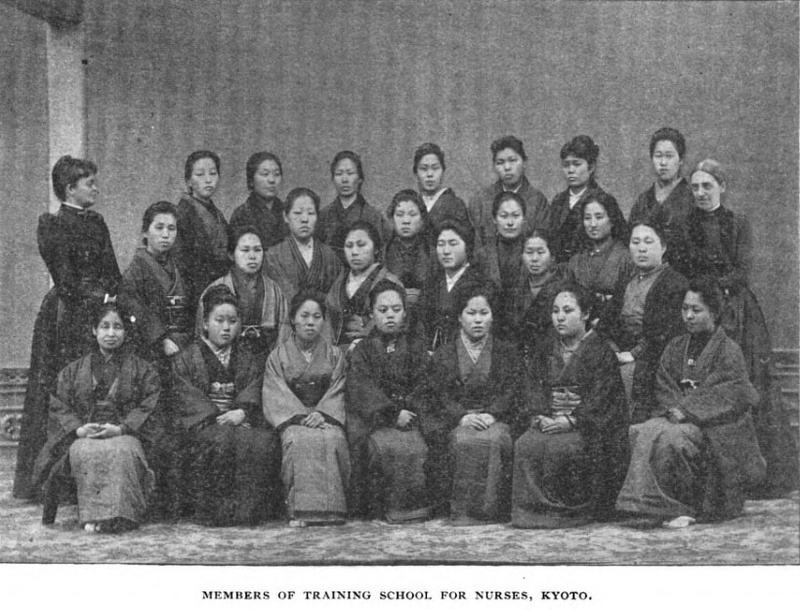

Back in Japan, Yasu registered herself as a medical doctor in April 1891. She was one of 13 female doctors then.24 Yasu was reunited with Sarah Cummings, and they worked together in Kyoto until about 1902.

Notes:

1. The Encyclopedia of Chicago, page 687.

2. Northwestern University Catalogue 1891-1892.

3. University of Chicago Annual Register 1905-1906.

4. Harrison, C, (1889) A Race with the Sun, page 66.

5. Berry, J.C. (nd) Medical Work in Japan, page 3.

6. Annual Report of IL State Board of Health, Vol.20, 1898, Official Register of Legally Qualified Physicians,page 205

7. Chicago Times-Herald, dated Nov 10, 1895.

8. Lublin, E, (2010), Reforming Japan, page 37.

9. Yasutake, R, (2004) Transnational Women’s Activism, page 33.

10. Woman’s Work for Woman, March 1884.

11. Ibid.

12. Dickenson, R, History of Northwestern University and Evanston (1906), page 127.

13. Nakadzumi, H. Kanagawa ni Miru Jyoi no Kiseki, (2001) page 132.

14. Catalogue of students for 1886-7 in Eighteenth Annual Announcement of the Woman’s Medical College of Chicago Session of 1887-8, Catalogue of students for 1887-1888 in Nineteenth Annual Announcement of the Woman’s Medical College of Chicago Session 1888-1889, Graduating class 1888-1889, catalogue of student for 1888-89 in Twentieth Annual Announcement of the Woman’s Medical College of Chicago Session 1889-1890.

15. Alumnae of the Woman’s Medical College of Chicago 1859-1896, (1896), pages 145-146.

16. The Northwestern Christian Advocate January 26, 1887.

17. The Advance August 11, 1887.

18. Nakadzumi, page 132.

19 . Daily Inter Ocean, November 22, 1890.

20. 1889 Chicago city directory Yasu Hishikawa, doctor, 114 S Wood.

21. Alumnae of the Woman’s Medical College of Chicago 1859-1896 (1896), pages 145-146.

22. Daily Inter Ocean, November 22, 1890.

23. Chicago Daily Tribune, Nov 22, 1890.

24. Misaki, Yuko, (2008) Meiji Joi no Kiso Shiryo.

*This article was based on a paper presented at the 20th Annual Conference on Illinois History on October 5, 2018, in Springfield, IL.

© 2018 Takako Day