A smiling lady behind the counter where the cashier is located welcomes and thanks those who enter and leave the place, in the middle of the Liberdade neighborhood. Owner of the traditional Japanese pastry shop Yoka, Luiza Yokoyama, 65 years old, has a surprising family story.

Nisei dedicated himself completely to raising and educating his children. To this end, he even prepared harumaki dough to sell. Until the age of 44, he decided to follow in the footsteps of his father, Japanese immigrant Takashi Yokoyama, and opened his own pastry shop with his help.

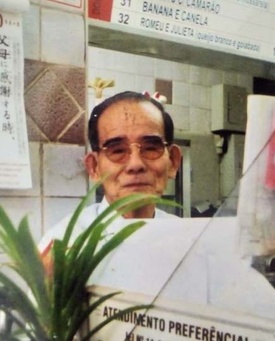

Pioneer Takashi Yokoyama

It all started with the arrival of his father to Brazil, in 1933, when he was 20 years old. “He came here with my uncle’s family, who was already married, and another aunt too.” Yokoyama worked on coffee farming for a few years and moved to São Paulo. “Then he started working for a family – my father even mentioned his surname, called Nakamura – that made pastries, but they weren’t from a store. It was wholesale, delivered to bars”, he says. And there he spent three years just learning how to make pastries. “No one else has continued in this family since my father started running a store.”

Takashi Yokoyama was the pioneer Nikkei in the field – the vast majority were Chinese. Many people who learned from him still make pastries today. “At the time, my father helped or gave job opportunities to people who came from Japan, people who were into judo. There were always people living at home, a small apartment...”, remembers Luiza.

In the 1940s, at the beginning of the war, Takashi was sometimes unable to buy ingredients, especially flour and oil, the most important ones. “He even said he was Chinese so he could buy it.”

Then, in 1945, after the end of the war, it resumed its activities. Dona Luiza recalls memories of when she was a child and her father had three pastry shops: “my father would carry us [her and her brothers] in the car, leave us sleeping and stop by the houses to take care of them. This story is very much from my childhood.”

By the 1960s, the number of pastry shops had increased and the newest unit was on Rua Cantareira, in the North Zone of São Paulo, the region where Luiza was born and raised. “There was a corner that I remember, there was a bakery and, next door, in a corner of the bakery, he had his pastry shop. And, at the time, as there was no Ceasa, the Cantareira market was the supply center for São Paulo. All the Japanese colonies that had farms and brought vegetables arrived there. People who are much older still remember that time when my father had a pastry shop. You know that longing?”, he continues.

The history of Yoka Pastry

Dona Luiza reports that she got married, had her two children and made an effort to offer them extra courses. When he was 44 years old and his children were grown, he decided to follow in his father's footsteps and open his own pastry shop.

“I had the opportunity to go to Rua da Glória, in Liberdade, it was a tiny place,” he says. After three years, he managed to rent the space that is the current address of Pastelaria Yoka, on Rua dos Estudantes, in the center of São Paulo.

In fact, the co-owner of Yoka reveals that she didn't know if she would enter this area, because “it's something you have to like”. “It’s not enough to just want it as a job, I think you first have to have the passion and be able to always think about it”, he says.

Because it is an activity carried out by the father, many people imagine that learning is passed on to their children almost automatically. But in this case, no. Luiza actually learned how to make pastries when she opened her store, at the age of 44. “In my adolescence, I always worked more in the customer service area, my father wouldn’t let me go into production, where the majority are men, because it requires physical strength”, he further reveals. And the reason is explained: she weighs less than 50kg and is 1.52m tall.

“But I took it hard too”, he says. It is very common for employees to leave the company and go to work in Japan as dekassegui . Then you have to get your hands dirty, literally. “I went through all the stages: I made esfiha, dough and there was a time when it was just me making pastry dough”. Today, with the help of technology, production has equipment that makes work easier. Even so, an attentive eye is essential: “knowing what the process is like, seeing, feeling the texture; To this day we suffer a lot.” The challenge of analyzing and getting the ingredients right belongs to his son Jobson.

Family business

Today there are three partners: Mrs. Luiza, her husband Roberto and her son who joined later. Before Jobson started working in the pastry shop, he went to do an internship in Japan. Having graduated in Hospitality, he spent eight months in Mie Prefecture working in the kitchen, which has always been his focus.

The creator of Yoka says she was lucky, because, if she didn't have anyone to be part of the business, she would have sold everything within about 20 years. “I have no attachment!” [laughs] “I think like this: I don’t think it’s because it’s the family’s responsibility that it has to continue, it has to have total freedom”, he explains. Luiza gives as an example her daughter who pursued the Administration field and is happy in the field. “She likes to eat, but she doesn’t like to cook. So when she started college, I didn't ask her to come here anymore. On the weekends, when I was in high school, she helped me a lot.”

Therefore, when his son returned from Japan he had to make his choice. In reality, Jobson was already determined to be part of Yoka. “He really likes working with me, it’s always been like that, you know?”, he celebrates. Somewhat rigid, the mother made it clear to her son that she needed a dedicated professional and not just a helper. The owner of the pastry shop felt the need to return to administrative work, to check on the general progress of the house and pay attention to customers. Therefore, she wanted there to be someone who only focused on the production part to adjust the recipe and supervise that everything is being done correctly. Translation: a person who was careful.

And no one better than “a brave boss”, as Dona Luiza defines her son, who is responsible for production. Jobson also took a Baking and Confectionery course, which helps – a lot – in practice. It is easier to test, for example, an ingredient that can be added.

As the popular saying goes, “you learn by making mistakes”. And that's what the person responsible for Yoka believes. “This fascinates and is the best part”, he declares. So, whenever you receive criticism, you think you can and should improve. Luiza has heard a lot that her establishment is already well-known, but – for her – having a name is “very little”. “We have to have results, reach the average of the majority, according to the taste, palate, history of each person”. And it recognizes that it must always change to improve and innovate.

The pastries

Currently, Yoka's menu has 20 savory and four sweet flavors, with meat and heart of palm competing for the title of best seller.

Furthermore, the menu gained a creation by Jobson, “pastenoli” – a version of the Italian sweet cannoli , made with pastry dough. The invention was well accepted, so much so that dulce de leche and cream are customers' favorite flavors, while chocolate comes next in preference.

Dedication as a mother

Dona Luiza's children have studied Japanese since they were nine years old, in addition to taking English and swimming courses. “I knew it was an investment, I started working because of that too. We fight a lot! [ laughs ] Regarding this, I tell my children, 'you don't have to demand anything that their mother didn't do in terms of study and training'”, he says.

And commerce requires a lot of dedication. “In my area, I spent more than 10 years without a day off, without a vacation, and we still work straight away here. Work holiday, Saturday and Sunday work.”

Passion for the kitchen

Luiza was already interested in the art of cooking. Before starting work at the pastry shop, for about three or four years, she made harumaki dough and supplied it to her cousin, in Yokoyama, and in grocery stores she knew. “I loved doing that! [ laughs ] I only stopped because of an opportunity,” he says. “I was ready to go into business.”

Once at home, she says she is very curious about testing new recipes. He even uses an app – which he loves – to get inspired and improve. Some “experiments” work, but others not so much.

Persistence

“Working little and earning a lot doesn’t exist [ laughs ]. At least at first. I no longer work like I used to, when I used to work 12 hours. I would go in first, open it, close it, I still had to go home and think about family dinner. I don’t think this is a sacrifice, because I think it’s an investment in improving yourself.”

That's why Dona Luiza says that everything involves learning: at first, it may seem difficult, but then the production line works thanks to your own work and it no longer depends solely on you. “You have to invest your life, your time. I think in any area, right? There are people who give up before they can succeed, because they can’t take it [ laughs ].”

© 2018 Tatiana Maebuchi