Hisa Nagano and Natsu Sakaki

In June 1886, Mary Clement Leavitt, the first representative of the worldwide missionaries of the WCTU, came to Japan. Leavitt gave lectures on a circuit from Tokyo to Nagasaki for six months and had an immense influence on Japanese Christians.

Leavitt gave a lecture in Kyoto as well. Orramel Gulick of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions had introduced her to Hiromichi Kozaki, future president of Doshisha English School, and Kozaki became an adherent to the principle of temperance. “The work being done by Mrs. Leavitt in Kyoto will further result in a total abstinence society for men, and a WCTU of seventy two members, exclusive of the missionaries, founded at Kyoto. All of the missionary ladies in the city will come in as advisory members.”1

It was in 1888 that Miss Mary Florence Denton went to Doshisha Girls School as missionary supported by the Woman’s Board of the Pacific. She had been a teacher and activist of WCTU in Pasadena, California before going to Japan.

Mary must have felt at ease about going to Doshisha, which had accepted the WCTU. While teaching at Doshisha, Mary combined temperance outreach with her mission duties. She appealed to union supporters in the United States for temperance literature to use in the classroom.2

Around the time of Leavitt’s visit to Japan, female missionaries’ efforts to open a training school for nurses began to come to fruition in several cities across Japan. The first, the Tokyo Charity Hospital and Training School for nurses, opened in 1885. Doshisha training school for nurses opened in 1887 in Kyoto.

Even though there were already training schools for nurses in Japan, Hisa and Natsu went to Chicago in 1892 because they had strong faith in the non-alcoholic treatment of disease. Their decision came through the influence of Miss Mary F. Denton.3

They “together investigated the Japanese hospitals and experienced a growing love for the work. But one feature of hospital practice … impressed these young women very strongly. They saw, in the free administration of alcoholic stimulants, the foundation of widespread evil. This resulted in the conviction that they must learn some method which avoided this danger.”4 Their dream was to open a hospital that made use of non-alcoholic remedies in Japan.

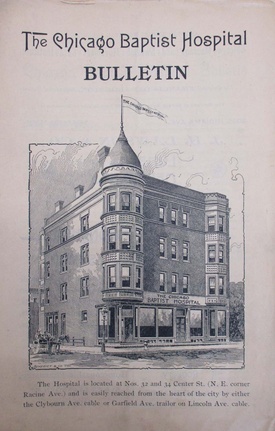

26 year-old Hisa and 21 year-old Natsu were under the special charge of the temperance women of Chicago, and took a two year course of instruction at the Clara Barton Training School for Nurses.5 They spoke good English and were determined to excel in the profession of nursing and their knowledge of non-alcoholic remedies, so as to help spread temperance principles and practice in Japan.6 At school, Hisa snd Natsu proved exceedingly capable, quick to comprehend, and were unselfish, untiring and absolutely truthful.7 In December 1893, Hisa and Natsu finished their training. It is said that at her graduation, Hisa received a gold trophy for excellence.8 After a very successful year of post-graduate work at Baptist Hospital,9 Natsu returned to Tokyo alone. Hisa, who was promoted to head nurse, did not leave Chicago.

The Chicago Evening Post reported on Hisa’s work as follows: “Hisa Nagano as a head nurse is unusually successful. Japanese woman beloved by all in the Baptist Hospital-learning how to help suffering humanity. The convalescent patients who leave the Baptist Hospital of this city confess, with one accord, that they have found a new kind of new woman. This latest type of femininity is of a remarkable variety, a rare embodiment of womanly graces. Hisa Nagano has qualities of peculiar power and sweetness to inspire in every patient and attache of this institution a personal loyalty and devotion which enshrines the shy little Japanese head nurse as scarcely less than a latter day saint.”10

Dr. Marion Ousley at Baptist Hospital, who had worked with Hisa and Natsu at Temperance Hospital, commented to a reporter that “ her touch is so tender and skillful that patients cannot accustom themselves to other hands after being used to hers. We consider her a marvel, as she never regrets to take the greatest pains with her work.”11

Occasionally some new patient under Hisa's care would send for Dr. Ousley and whisper mysteriously “I want another nurse.” In less than twenty-four hours, the doctor was again summoned. “Send the Japanese nurse back again-I like her to handle me best.”12

Hisa was full of energy in eyes of her colleagues in the hospital. One of her colleagues said, “Her hands and feet were very tiny, but she possessed a power of endurance that was hardly comprehended by the Americans who worked with her. I have seen her, in strenuous times, when the hospital was crowded with patients and short of nurses, stay out of bed day and night and day and night again, lean against the wall once in a while and sleep on her feet for a few minutes and then go on again, and keep this up until someone forces her to stop.”13

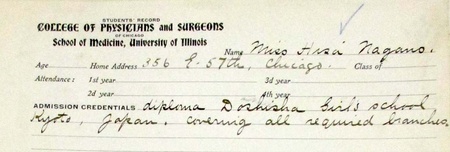

After about five years, Hisa went back to Japan in December 1898 to get some rest. But in Japan, she found that she disagreed with the orders given by physicians in Japan.14 In addition to the fact that there was less understanding and acceptance of non-alcoholic remedies in Japan, she must have felt the effects of the Japanese male physicians’ jealousy and discrimination against rare, professional Christian women such as herself. Frustrated, she returned to Chicago in February 1899, after only a two-month stay in Japan, and upon her return, she enrolled at the College of Physicians and Surgeons to become a medical doctor.

While boarding at Dr. Marion Ousley Russel’s house on East Fifty-Seventh St in Chicago,15 Hisa worked hard to finish a four-year medical school course in three years.

Toshiro Fujita, the Japanese consul in Chicago, had Hisa help his wife deliver their baby at home in October 1899, and was deeply moved with her excellent and kind care.16 Knowing that she got up before dawn and went to bed after midnight to study, Fujita advised Hisa not to rush her successes, but to attend to her own health and to study within her capacity. He admitted that her lack of sleep and overwork worsened her health.17

In addition to studying very hard for medical college, Hisa used her time to translate a Japanese romance story titled “Morning Glory” into English and left the manuscript to Mary E. Phillips at 249 Dearborn Ave Chicago, for publication. The Japanese consuls, Fujita in Chicago and Uchida in New York, remarked favorably onthe translation and allowed it to be mentioned in the press.18

Despite her energetic activities in her Chicago life and passion for the medical field, Hisa’s health failed and she had to go back to Japan in the fall of 1900. Consul Fujita advised her to return to her native land in order to die among her family and friends.19

She passed away on April 8 1901 in Kyoto. She was 36 years old. Consul Fujita’s words said everything about Hisa: “Many Japanese are staying in the United States. But how many Japanese are being treated with genuine respect from Americans? As she was such a sincere and a heartfelt real Christian, once Americans met her, they forgot that she is non-white, and treated her with much respect.”20

Inspiration - Universal Spirit of Pioneers

A female missionary left the following words on record: “If I were asked to give my opinion on the subject of sending a Japanese girl abroad for education, I would say, unless … she is a rare woman who can modestly but firmly maintain her dignity against the pressure of public opinion, and not be made very unhappy by being ignored or misunderstood, it is much better to remain in Japan…21

In New York in 1910, the Japanese scholar Baron Kikuchi, president of Kyoto University and formerly Minister of Education in Japan, was asked by the audience, “Has Japanese civilization been influenced by Christian missions?” He gave a prompt and decidedly negative answer, but afterwards added, “Of course they have given inspiration to young Japanese students.”22

Inspiration -what else do we need to live fully in this world?

Yasu, Hisa and Natsu all died when they were still young— in their 30s. It is easily imaginable that their student life in Chicago was sometimes very lonely and harsh for these young women. But their spirit, pride, and strong will, that matched the same spirit of the American female missionaries who came to Japan should be remembered as a universal driving force that has changed history and empowered Japanese women, even today.

Notes:

1. Lublin, page 24.

2. Lublin. Page 82.

3. The Union Signal, September 8, 1892.

4. Chicago Evening Post, February 20, 1897.

5. The Union Signal, September 29, 1892.

6. Life and Light for Women, September 1889.

7. King, W. World Progress: As Wrought by Men and Women (1896), page 187

8. Doshisha Jogakko Kiho No.2 June 6, 1894.

9. King, page 187.

10. Chicago Evening Post, Feb 20, 1897.

11. Washington Times, Jan 17, 1897.

12. The Morning News, Jan 4, 1897.

13. Modern Hospital Vol 10, No. 6, June 1918, page 434.

14. Life and Light for Woman, September 1900.

15. Illinois Census, 1900.

16. Doshisha Jogakko Kiho No. 19, June, 1903.

17. Doshisha jogakko no Kenkyu, page 29-30.

18. Mary E Phillips letter to Griffis dated Dec 11, 1904, Japan Through Western Eyes, Part 4: The William Elliot Griffis Collection Reel 35.

19. Ibid.

20. Doshisha jogakko no Kenkyu, page 29-30.

21. Life and Light for Woman, October 1893.

22. The Open Court, July 1911.

*This article was based on a paper presented at the 20th Annual Conference on Illinois History on October 5, 2018, in Springfield, IL.

© 2018 Takako Day