In 1897, Japanese workers began to arrive in Mexico as part of the friendship agreement that was signed in 1888 between both governments. At first, farmers arrived in Chiapas, workers in the mines of Coahuila and Chihuahua, day laborers in Veracruz, and fishermen in the port of Ensenada in Baja California where they dedicated themselves to capturing abalone and other marine species.

Later in 1917, thanks to an agreement signed between Japan and Mexico, doctors, dentists, veterinarians and pharmacists were allowed to freely practice their profession. It is estimated that more than fifty Japanese professionals arrived in Mexico to work in different places in the Republic before the war broke out in 1941.

However, a few years before the signing of this agreement, some doctors were already living in Mexico. One of them was Dr. Kendo Koi who arrived in Otatitlán, in the region of Papaloapan, Veracruz in the year 1916. At that time, the doctor had turned 28 years of age and it is not known exactly what the reasons were. They made him move from his hometown of Hiroshima and settle in the midst of the revolution in this region.

When Dr. Koi entered Mexico, there were already about three hundred Japanese living in that state, mainly between the cities of Acayucan, Minatitlán and the port of Coatzacoalcos. In the same state of Veracruz, the “La Oaxaqueña” hacienda was located, a sugar plantation where in 1906 a contingent of about a thousand Japanese arrived, hired to cut sugar cane and make the candy. The unsanitary conditions on this plantation caused several workers to die from malaria and gastrointestinal diseases, so in that place we can still find their tombs with inscriptions in the Japanese language. On the other hand, the terrible labor situation of the workers led the vast majority of immigrants to desert and go to other places in Mexico.

It is likely that these pioneers were the ones who would help Dr. Koi settle in the town of Otatitlán. At the end of the revolution, Mexico did not have enough doctors, so Koi's presence represented great relief and help for the population. To practice his profession in Mexico, his doctorate degree was recognized at the National University. His work and dedication were highly valued by the population and the local authorities from the beginning.

In a few years of stay, the doctor was already fully integrated into the life and customs of the residents of Otatitlán. In 1923, Koi married a young Mexican woman, Miss Carmen Bogard, who was originally from the place and with whom he had six children.

Two years before Koi's arrival in Veracruz, in the city of Acayucan, another Japanese, Junsaku Mizusawa, was already living, with whom over the years he would establish a deep friendship. This young Japanese man, originally from the Niigata prefecture, arrived in Mexico at the age of 25 and joined one of the small businesses that one of his countrymen had in that town. In 1925, Mizusawa moved to the town of Otatitlán to help Dr. Koi; At his side he acquired theoretical and practical knowledge of medicine, but he also trained in the preparation of substances that served as medicines to relieve the pain and illnesses of patients. Mizusawa thus opened a pharmacy where he would begin to serve his patients.

Dr. Koi moved his office to Papaloapan, a few kilometers from Otatitlán, in the state of Oaxaca. In this way, these isolated and poor populations, located on the banks of the Papaloapan River, were able to count on doctors and medicines.

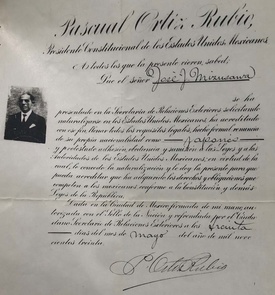

Due to the work that Alfredo Koi and José Mizusawa carried out in these towns, as they would be recognized, they managed to establish deep and close relationships with their inhabitants throughout these years, which allowed them to take root and feel like part of these towns. . For this reason, both began the procedures to request Mexican nationality before the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in 1927, a request that was finally granted three years later.

At the outbreak of the Pacific War between Japan and the United States in December 1941, Mexico severed its relations with Japan and was forced, under pressure from its northern neighbor, to exclude from its borders and coasts all Japanese immigrants and their descendants. To meet that objective, the Secretary of the Interior ordered all Japanese and their families to concentrate in the cities of Guadalajara and Mexico so that they would be closely monitored.

In mid-1942, Dr. Koi and Mizusawa received telegrams instructing them to immediately move to Mexico City. At first, both doubted that they could be included in the lists of concentrates since they were already Mexican citizens and had renounced the protection of Japan.

The transfer and concentration orders that Koi and Mizusawa received were therefore totally illegal and were due to a racist and discriminatory vision that considered that just because they had Japanese blood was sufficient reason to concentrate them. Even so, Koi and Mizusawa moved to Mexico City and immediately reported to the Directorate of Political and Social Investigations, the body in charge of monitoring the Japanese.

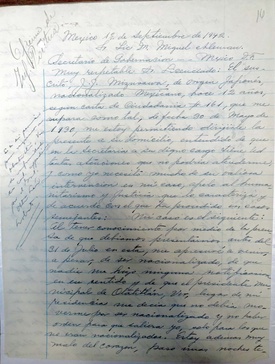

In the naturalization letters, the Japanese accepted their “adhesion, obedience and submission” to Mexican laws and therefore enjoyed all the rights and obligations of Mexicans. José Mizusawa himself wrote in his own handwriting a letter in Spanish addressed to the Secretary of the Interior, Miguel Alemán, where he respectfully asked him, as a Mexican citizen, to allow him to return to his beloved town of Otatitlán.

The transfer of Koi and Mizusawa to Mexico City immediately caused great concern and protests from the residents of Otatitlán and Papaloapan because they considered that such a measure, in addition to being unfair, was detrimental to all of them who were suddenly affected by not having with the attention of his beloved doctors.

The municipal authorities themselves and the military commanders installed in this region were also dissatisfied and immediately sent letters to the Ministry of the Interior to request the return of Koi and Mizusawa. In these letters, the municipal presidents explained that both were honorable, honest people, respectful of Mexican laws, in addition to being exemplary citizens. On the other hand, agricultural organizations, workers and the population in general wrote letters to the federal authorities to inform them that the services provided to the population by the naturalized Japanese were necessary and that they had also given themselves selflessly to the service of the community. Because on many occasions they did not charge for consultations and gave away the medicines to patients who did not have sufficient resources.

Given these clear and forceful requests from the residents and local authorities, the Secretary of the Interior authorized the return of the doctors a few months after their transfer to Mexico City. One can imagine the great joy that the return of Koi and Mizusawa caused in the population, who were able to continue caring for their patients, but unfortunately not for long.

José Mizusawa, a few months after returning to Otatitlán, died of a heart attack at the end of 1943. Dr. Koi, at the end of the war in August 1945, received with great sadness and affliction the defeat of the country where he was born; Above all, he was greatly hurt by the dropping of the atomic bomb on his hometown of Hiroshima, where more than 100,000 people died at the time of the explosion. Although he became a naturalized Mexican, the doctor did not stop feeling great regret upon knowing that hundreds of thousands of innocent people had died without being part of the imperial Japanese army. Koi died a year later in the town of Otatitlán where his remains rest, in the same cemetery where Mizusawa was buried.

* Article prepared with the collaboration of Jumko Ogata .

© 2018 Sergio Hernández Galindo