As I travel around Washington state giving talks about Japanese American history, the question often arises: Did they have incarceration camps in Hawai‘i? Indeed, even activists involved in education and preservation of the ten primary World War II camps on the Mainland, often know little of the camps in Hawai‘i.

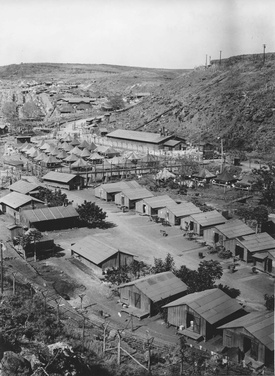

Following the bombing of Pearl Harbor, as many as 17 sites were designated, across all the Hawaiian islands, from local jails and courthouses to a plantation gymnasium, with the purpose of detaining Japanese and Japanese Americans who were suspected of possible espionage or breaking the rules of martial law. A temporary detention camp was built immediately after the Japanese Imperialist government bombing attack, at Sand Island, as part of the Pearl Harbor military installation. Later, Sand Island was closed when Honouliuli Internment Camp, the largest of the Hawaiian camps, and incorporating a prisoner of war camp with men, women and children from many nations, was built in western O‘ahu in the ‘Ewa area, near Waipahu in March 1943. The large natural gully trapped the searing heat and had no views out of the area. As many as 4,400 inmates were forced to live there for three years, mostly in tents. “Jigoku Dani” or Hell Valley, was the Japanese name given to the site.

The story of life at Honouliuli Internment Camp for the 400 interned Japanese and Japanese Americans is horrific. It was hot, dusty, bug infested, and boring. But the camp additionally held as many as 4,000 prisoners of war (POWs) from both the Pacific and European fronts. Many were Germans, but also included Irish, Italians, Russians, and Scandinavians. Also POWs who had been held or conscripted by the Japanese government were interned there, including Koreans, Taiwanese, and Filipinos. Often, the ethnic groups had to be physically separated due to historic animosities.

Interestingly, the military guards at Honouliuli were mainly comprised of African American and Japanese American segregated units from the Mainland.

Martial law in Hawai‘i continued from December 7, 1941, to October 24, 1944, and meted harsh treatment on the civil liberties of 158,000 persons of Japanese descent in the islands. In the prewar period, this ethnic group reached the high of 42 percent of the population there and they were essential to every business, agricultural and social aspect. Eventually, 2,263 of these were picked up, processed, and imprisoned in one of the many camps. Some of the Japanese or Japanese Americans were sent to the ten Mainland incarceration camps or Department of Justice secret camps. An additional group of 1,500 were evicted from their homes with no recourse, although they were not interned.

In Hawai‘i, Japanese and Japanese Americans should be called internees because, under martial law, they each underwent a hearing to determine guilt or innocence, as stated in the National Park Service’s study of Honouliuli and the other internment sites. This is a dramatically different scenario compared to the 120,000 people of Japanese descent on the Mainland who were sent to camps purely because of their racial group, with no individual hearings or trials to prove guilt.

In 2002, community activists and scholars working with the Japanese Cultural Center of Hawai‘i (JCCH), discovered the outlines of the original WWII buildings of the Honouliuli Internment Camp. Thus began a series of projects funded with National Park Service grants, under the umbrella of the JCCH education center, “to honor those incarcerated at the Honouliuli internment camp and all persons of Japanese ancestry arrested and detained throughout Hawai‘i during World War II.”

Following federal legislation to study Honouliuli as a possible unit of the national park system, the National Park Service compiled a major study to evaluate all 17 sites in Hawai‘i and determine their significance for further protection and programming. Two of national significance were the Federal Immigration Station in Honolulu, where all Japanese immigrants and internees were processed, and the Honouliuli Internmentl Camp site.

In February 2015, President Barack Obama issued a proclamation establishing the site as the “Honouliuli National Monument” under the jurisdiction of the National Park Service, like several other WWII incarceration camps.

Under President Obama, consideration was actively given to diversifying the national park system to represent the diversity of all American people. Sites like Cesar Chavez National Monument, the Wing Luke Museum of the Asian American Experience in Seattle, the Stonewall site of significance to the LGBT community, and women’s sites also were designated, as well as important African American and Native American sites.

At first, no locals knew about the Honouliuli site. It was hidden in a valley on private land, the Campbell Estate, and continued to be privately owned as the Monsanto Company purchased it in 2007. Monsanto wanted the surrounding area for agricultural testing. However, as this land also included the Honouliuli Gulch site, eventually Monsanto donated the 120 acres of the Honouliuli site to the NPS in 2015.

Another important community partner has been the University of Hawai’i West Oahu, which is located adjacent to the site, and has provided many archaeology student and faculty volunteers to excavate the Camp grounds.

JCCH opened its excellent exhibition on the Honouliuli Internment Camp at its cultural center space in the Mō‘ili‘ili neighborhood of Honolulu in October 2016. The JCCH also has published studies, made films, and is creating a database of Hawaiians of Japanese descent who were interned in WWII. The JCCH has collected oral histories from some of those few internees still alive that experienced the camps. The Cultural Center also has mounted an extensive exhibition on the Gannenmono, the first Japanese immigrants to Hawai’I, who came 150 years ago.

As for next steps to opening the Honouliuli National Monument site, issues such as lack of access roads must be solved. It will be open to the public eventually, after a multi-year planning process, as was conducted with other incarceration sites such as Minidoka and Tule Lake. There are no standing buildings or visitor services at the site currently.

The JCCH is dedicated to further research and documentation to add to its current curriculum projects that share information about Honouliuli Gulch and Japanese American internment with a new generation of Hawai‘i students.

***

For more information:

Japanese Cultural Center of Hawai‘i

To see the JCCH film: The Untold Story: Internment of Japanese Americans in Hawai‘i

Densho Encuclopedia, “Honouliuli (detention facility)”

* This updated version of the article printed in the International Examiner published on August 15, 2018, includes slight revisions provided by sources.

© 2018 Mayumi Tsutakawa / International Examiner