Growing up Sansei in my part of California’s San Gabriel Valley meant you didn’t have to work very hard to stay connected to your Nikkei roots—they were all around you. Every family that lived on our South San Gabriel street was Japanese American. We shared Japanese food, holidays, and a mania for gift giving. Our most exotic neighbors were from Okinawa, which as a child I took to be a country separate from Japan. Our local Issei “fish man” would come by weekly his truck to sell the neighborhood moms sashimi-grade tuna and fresh tofu, and our favorite Botan ricecandies wrapped in rice paper. I think he sharpened knives, too, those dark and mottled Japanese houcho that my mother used. Japanese traditions were so much a part of our lives that it seemed perfectly normal when my friend Jessie said she had to knock off playing in the afternoons to go home to wash the rice for that evening’s dinner.

My actual roots, my Issei maternal grandparents, lived close by. Their culture of the Japanese-language Rafu Shimpo and Kashu Mainichi, koto playing, tanka poetry clubs and trips to Yaohan market in Little Tokyo formed an offshoot to our daily lives.

It wasn’t until I was much older, and living on the east coast that it became possible to think of my roots as something I needed to return to in some way. I was a journalist by then, and could view them as material, stories to write about.

Two projects in particular took me back to those roots in a deep and meaningful way. One was a lengthy essay series I wrote for Discover Nikkei on the documentary photographs of Manzanar, where my father and his family had been imprisoned during World War II. The camp held a special fascination for me because while my father was living, I don’t recall him even once telling a story about it, or about Tule Lake. Barely a teen, he accompanied his father and one of his older brothers to that notorious Northern California prison camp after they answered “no” and “no” on the government-issued loyalty questionnaire.

Like most Sansei adolescents, I didn’t know much about the questionnaire or the camps, and didn’t much care about them. They were ancient history and could not possibly be relevant to the gripping drama I was living as a teenager among other teenagers. By the time I did become interested in that chapter of my father’s life he was gone. I regretted the lost opportunity of asking him to share his stories.

My interest in those documentary photos began when I learned that Ansel Adams and Dorothea Lange had documented the camp. I admired these iconic photographers of the west, and wanted to learn more. Immersing myself in the details of their trips to Manzanar, and of the prison camp itself, I realized that in 1942—when my father was pulled away from school and friends and bused to Manzanar under armed guard—he would have been only 13 years old. That was how old my own son was at that moment. For the first time, I understood how terrifying those experiences must have been for my father.

Writing about the prison camp photographs was a way to understand, or help me imagine, what life in the concentration camps must have been like. They were also enigmatic and baffling. Why so many smiling people? Where were the shame, humiliation, and loss of dignity that I knew had destroyed some of those imprisoned, especially among the Issei generation? The series was an exercise in examining my roots and realizing the limits of my ability to fully understand what my family experienced in those prison camps.

Last year, the chance arose to contribute an introductory essay to a book called Displaced: Manzanar 1942-1945, The Incarcertaion of Japanese Americans. A collection of photographs, it features the same photographers I wrote about. This was an opportunity to reach a wider audience, for those outside my tribe to hear our stories and understand our struggles. Connecting with our Nikkei roots helps us understand who we are and where we came from. Sharing stories of our culture and history with others, I hope, will increase understanding and tolerance between races and cultures.

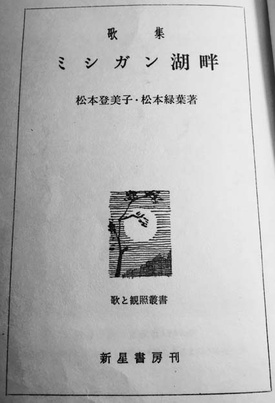

The second project that connected me to my roots is a translation of a book of tanka poetry that my maternal grandparents published in 1960. They shared a small corner study in their home in Rosemead, California, where they wrote their poems on two wooden desks, each placed before one of the room’s two perpendicular windows.

In 1960 they published a collection of their poems, Mishigan Kohan (ミシガン湖畔 / By the Shore of Lake Michigan), which chronicled their lives over a seven-year period, beginning with their forced relocation from Los Angeles to Heart Mountain, Wyoming in 1942, and continuing through their move to Chicago at war’s end. The collection ends in 1959, shortly before their return to Southern California.

One of my grandmother Tomiko’s poems was selected in 1955 for the Japanese Emperor’s annual New Year’s poetry reading. A framed, yellowed newspaper article from The Chicago Sun Times adorned the pink study,headlined, “Lonely Heart Wins Jap Prize for Poetry.” The “lonely heart” referred to the nostalgia she expressed for her home village in Chiba Prefecture. The poem read:

Moonlight

filtering through the trees

onto a clear, flowing spring—

such serene beauty

cannot be found in this country

Working with two talented translators, Kyoko Miyabe and Mariko Aratani, and later, Amy Heinrich, we parsed each syllable of the poems, debating their meanings and allusions, and agonizing over translation syntax, word choice, tone, and rhythm. It was painstaking work, yet when we arrived at a solution we all liked, exhilarating as well. I gained more insight into the passions, sorrows, doubts, and happiness of departed loved ones through this process of poetry translation than through any other I’ve encountered.

I knew that my grandparents, for instance, had loved nature and gardening. But through the dozens of references to plant, tree, and flower varieties that we translated—specimens they spotted on walks, gave and received among friends, and cultivated in apartments and in gardens—I understood how specific, visceral, and central to their lives that love was.

I don't recall hearing my grandfather speak about the war, or the village he grew up in. But translating the lengthy group of poems he wrote in the immediate aftermath of the war made me understand how passionate his love of his homeland was, and how much it pained him to see his American-born children side with the U.S., and his country go down in defeat.

Here are just two examples, written about Armistice Day, when the news of Japan’s unconditional surrender was announced:

My Nisei children

who do not know Japan

spend all day long

at the radio

rejoicing over peaceIn the end

not having anywhere

to put my feelings,

suddenly I stand

and let tears fall

I’m now seeking a publisher for this translated work. Like the Manzanar essay, what began as a personal examination of my family and my roots has expanded into something larger. In this case my hope is to help shed light on the inner lives of the Issei generation. Though their thoughts and feelings were widely recorded in Japanese-language poetry journals, newspapers, diaries, and letters, most of that trove remains untranslated. By the Shore of Lake Michigan is my attempt to help fill in that gap, and pay tribute to the Issei generation to which we Nikkei owe our existence.

Our ways of connecting to our roots are as different as each of us is from another. Whatever your method of choice is, I hope it brings unexpected and outsized rewards to you, as it has for me.

© 2018 Nancy Matsumoto