"I remember being strafed because I was in the factory. And so I guess they knew which ones to bomb. I remember every time this siren would ring, we reluctantly put our helmets on and run into the forest. And at that time I really prayed to God.”

— Ann Sato

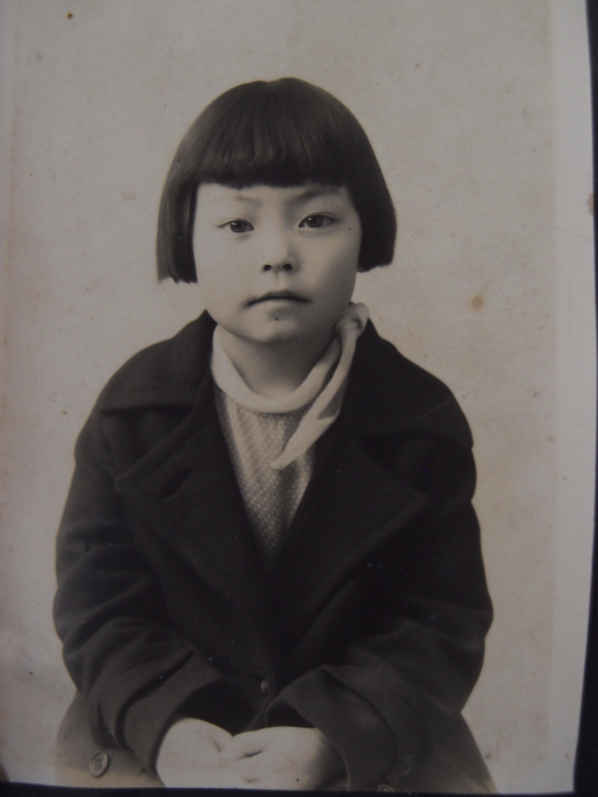

After taking the last ship back from sunny Southern California to Japan with her parents and sister in 1940, Ann Sato’s life was completely upended with the escalating tensions between the United States and her parents’ home country. Her siblings all found themselves on opposite sides of the globe and the war: Her brother Jimmy lost the successful family grocery store in Torrance and was sent to camp in Rohwer, while Muraji, who was raised in Japan served in the military in Manchuria, and her youngest brother, Hiroshi, served in the American Military Intelligence Service. Ann vividly recalls a last moment with him before they parted. “I remember he took my roller skates apart and oiled it, packed it, and it was really sad for me. I understand that after he saw us off the pier he went back and cried and cried. He was 16.”

And while Rosie the Riveter took shape as a progressive symbol of women’s independence and empowerment through the war effort, Ann herself became Ann the Riveter, assembling plane engine covers by hand in a Mitsubishi factory. As a high school student, she watched the war play out terrifyingly close when American bombers would eventually come down and strafe their area of the factory, sending her running into the forest with the other children. Struggling to find a safe hide out among the tree roots, this would be the one time in her life that she would “really pray to God.”

Let’s start at the beginning with where you grew up in the United States, and then can you share the story about going to Japan?

I was born in Torrance, California and I had just entered junior high school there when my parents decided, I think [we were] on the last ship to Japan, before the war started. And so I went to my mother’s village, where she lived and there was a house two villages away. It was the Daimaru [department store owner’s] house, it was their summer resort. And so we decided we’ll buy that and take it to my mother’s village where she lived. And actually it was a bigger city and it was better for us actually to just stay there.

I see. And where was your mother’s village?

Esumi.

Esumi. OK. And where is that?

It’s in southern Honshu in Wakayama prefecture. And then, so I tried to enter the high school there after sixth grade I guess, and I couldn’t get in because I was so behind in my Japanese, actually.

Did your parents speak Japanese to you in Torrance?

I went to Japanese school in Torrance. And the teachers came in from L.A. They had their regular schooling during the weekdays. They came I think on Saturdays and we spent one whole Saturday there.

Did you enjoy that or did you kind of not want to go to Japanese school?

I didn’t mind it I guess. I kind of enjoyed it because you get to see some of my friends, you know.

Right. Yeah it was kind of fun. So in Japan though, you were behind in your language skills?

Oh yeah. And so I think we were on the last ship to Japan on the Tatsuta Maru. And so I was a year behind in my classes there.

Wow. And what was it like, how long did it take to get from California to Japan?

I think it was let’s see, I used to know all this, I forgot, it’s been so long. I think it was like two weeks almost? It stopped in Hawaii to refuel and it was a long voyage I remember.

Very.

And I remember tossing those tapes, you know.

The tapes?

Yeah. We used to have colored tapes and we used to toss it to our friends. The big tapes. And that would eventually break and I would be crying, and I had to go back to my cabin. And not knowing what Japan was like of course.

And were you with siblings?

I had an older sister. And my brother in-between us was ready to go on to college, so he stayed behind with my older brother. And we left the grocery store to him.

So your parents ran a grocery store?

It was right on the demarcation of Torrance, on Torrance and Hawthorne Boulevard. We were in Torrance and across the street was Redondo Beach. And there was a grocery store there but theirs was much smaller and all the customers, I remember, were in our store because we had a gasoline tank and it was a big, big store and theirs was kind of small, you know. I remember my parents saying when I was small they said, ‘What are we going to do with all of this money?’ You know, they were successful. And so they said we’ll go to Japan and leave the grocery store to my oldest brother, who took on a wife.

Oh, wow.

And so my father and my mother and my sister and I were taken to Japan and left the grocery store to my older brother.

Wow. And your parents were Issei?

Yeah. They were Isseis.

So they had a true, kind of American dream happened for them.

Yeah. They had a brand new truck and a new Oldsmobile, you know and we left everything to my oldest brother who took on a wife.

And then the year that you left California was that –

1940. Right before the war started.

Wow.

And so they were put into camp and they lost everything of course. I remember they [her parents] were rushing around getting passports and everything. And apparently, and I think they knew that the war was going to start. I remember they were rushing around and I had to go take photographs and you know, all that kind of stuff. And we were on the last ship to Japan.

And so you were looking forward to a new life in Japan?

Sort of. I knew I had cousins there that I knew because I visited Japan before. And they had a big family. And he was a veterinarian so they were quite wealthy in that village, you know. So I went to live with them and my parents stayed with their parents, my mother’s parents.

Going through school, even if your Japanese wasn’t to the level of someone who lived there. How was it?

One good thing was that I looked like them.

Right.

So they accepted me right away. First I remember they made this ring around me and then I remember they were saying “zippa, zippa” because my mother made my dresses, and she put a zipper on my dress.

Because that was uncommon for Japanese style to have zippers?

Yeah, I guess it was rare in those days and my mother was a sewer and so she made all my dresses. So she put a zipper on here and I couldn’t wait for the bell to ring.

They were like: “Who is this new person?”

Yeah. And you know they don’t, they don’t say “Come on with us” or anything they just make a big ring and they squat, you know in Japan. They don’t sit down on the ground. But they sort of squat and they can squat a long time. And I can’t do that.

It’s something they just grew up doing, right?

Yeah. And so they all made this ring around me and I couldn’t wait for the bell to ring, I remember.

But everyone was friendly or, you didn’t feel–

Oh yeah, they accepted me right away because I looked like one of them, you know. Which is a good thing. I got along with them fine.

So you had about a year of school before Pearl Harbor happened. And do you remember what happened that day? Do you remember the day that you heard that?

I don’t remember that day too well. I know we left the grocery store to my oldest brother and the youngest brother was ready to go on to college. So we left him and as I understand it, I remember he took my roller skates apart and oiled it and packed it for me and it was really sad for me. And anyway, I understand that after he saw us off the pier he went back and cried and cried. He was 16, you know.

Oh my gosh. That was your younger brother?

Well he is older than me. I’m the baby.

Right. So then do you have two older brothers?

Yeah. I had three older brothers and one older sister.

So what are the names of your siblings?

Jimmy Hamano, James. And then next was Muraji, who grew up in Japan. He was left with my grandparents. And then Hiroshi. And I had an older sister that went to Japan with me, her name was Sachiko.

So the boys stayed and the girls went back to Japan, basically.

Of course they were all put into camp here.

Right. So how did you and your parents find out that they were getting sent –

I can’t remember but they said that if you wrote a letter to them, they will eventually get the letter. So I remember writing to them on a postcard, you know, and I guess it eventually got to him.

Do you know what camps they were in?

Rohwer. Arkansas.

That couldn’t have been more different for them coming from Southern California. And did they try to write to you in Japan during camp?

I remember we really struggled to let my brothers know that our father passed away after a year in Japan. And we didn’t really know whether they got the letter or not through the Red Cross, you know.

Oh no. So your father passed in 1941?

Yeah, about 1941.

Was that unexpected?

Yeah, he had a heart attack. I know they were both heavy, you know kind of obese. And I remember he used to smoke cigars, because he was told not to smoke anymore, so he used to just puff on his cigar. So apparently, he had heart problems, I guess.

So the war began when or with the U.S. and was that just you, your sister and your mother and your grandparents?

My grandparents, yeah. Yeah we bought a home and we were going to take that house, so we were going to take it apart and take it to our village that my parents grew up in and they lived there for a while and they said this is a much bigger city so they decided to stay there. So we just stayed there instead of taking the house back to my mother’s village.

Were you far enough away from what was going on in Tokyo and the fire bombings?

There were blackouts and you know, things like that. Air raids. In the meantime, I went to school there.

Where was the prefecture, your new school?

It was Arita. Well it was about three hours away I guess on the train.

Yeah that’s long.

That’s pretty long for Japan.

It is. And your mom was alone. And then what was your sister doing?

She was in Tokyo, and she went to Tokyo to look after my uncle’s two little children and then she couldn’t get a ticket back home. In those days it was very hard to get train tickets.

How come?

I don’t know. I think first of all, a lot of the trestles and tunnels were bombed.

Right. No way to get across, get through.

Yeah. And I remember being sent to a war factory – I was still in high school and I was sent to a war factory. It was Mitsubishi at that time.

And where was that factory?

It was a city in Gobo. But I remember we stayed in a dorm and went to work every day.

What were you doing? What was your work?

Making airplane engine covers.

Oh, wow.

So I was Ann the Riveter.

Exactly. And this was obviously to help Japan’s war effort?

Yes. And by riveting these rivets into the engine cover, you know it’s all done by hand [laughs].

That’s incredible.

Later on, I saw that Rosie the Riveter in America had this [Ann motions the riveting machine] and here we’re using the hammer.

Right. That was all – there was no riveter.

Riveting machine.

Riveting machine.

I remember doing that. I remember getting these little nails you know and having it, iodized or boiled anyway in some kind of chemical so that it becomes pliable and becomes soft. And I remember hammering it on to make the engine covers.

So you were responsible for those planes that went, that was your handmade work. That’s amazing. And why did you start working?

Well, I was in high school. And the school was sent there.

Oh, the whole school?

Well I was, let’s see what year was I in? The first two years, they helped the local farmers because the men were all sent to the army. So the first and second year I think were sent to the local farmers helping them plant rice or whatever work there was on a farm. And the third and fourth year students were sent away to war factories.

* This article was originally published on Tessaku on July 10, 2018.

© 2018 Emiko Tsuchida