Return

In 1992 my mother suddenly made the decision to return to Argentina. In February he sent my brother to Buenos Aires because the start of school was approaching and he didn't want Leo to fall a year behind in high school. At that moment I didn't ask any questions, I just told him that if he wanted to come back so that the five of us could be together, that is, my maternal grandparents and the three of us, I agreed. We had to sell the laboratory, send a container by ship with our personal effects and the car. We had to process all the necessary documents for the international move if we wanted to return as soon as possible. The real reasons for returning to Argentina were other. I discovered that my mother was very sick when there was nothing more to do. Leaving Italy after seven years of absence was a prudent security measure to not leave my brother Leo and me alone in Europe.

In Buenos Aires, in 1993, instead of starting treatment to cure herself, my mother contacted Mary Higa again and once again resumed her fight as if not a single day had passed. I wanted to find answers, I wanted to know what had happened to my dad.

Our return coincided with the arrival of Italian judges to Argentina to collect testimonies and evidence about missing Italian citizens. That time my mother spoke to the Italian judges but left without achieving anything since the only witness who saw my father in the Clandestine Detention Center “El Vesubio” had gone into exile and never told us where he was going.

On February 28, 1995, my mother, Edvige “Beba” Bresolin, died in Buenos Aires surrounded by family and friends, including Mary Higa. My mother remembered my father until the end, calling him by name in intermittent moments of sleep. Surrounded by love and gratitude for everything he sacrificed for us, for everything he donated to us, cared for, taught, loved, I think that my old man deserved the same when his time came.

When my mother died, the climate in my maternal grandparents' house, which was where we had returned to live, was unbearable. My grandfather had gotten sick a few years before with senile dementia, but no one had told us until we saw him and he didn't remember who we were. A true tragedy because he was one of the smartest, kindest people I knew, he knew everything, he also like Takashi, always with a book in his hand, we spent hours talking in Italian about stories from when he was a child and the First War World, but he also made me laugh when he sang me songs, putting me as the protagonist in the lyrics. Takashi and Mario loved him very much. He told me about when Takashi and he went to the Molino cafeteria that was in front of Congress, to discuss politics, but my father did it in Italian, the people's faces made them laugh when they saw that a “Japanese” spoke in Italian. Italian.

My mother realized that perhaps returning to Argentina had not been one of the best ideas and that we were going to be better off in Italy. Beba told my grandmother Teresa that when she was gone, Leonardo and I would return to our ideal environment. He also spoke with Marisa's parents, Delia and Julio Uehara to make sure we are okay. I discovered those conversations my mother had many years after she passed away.

For a long time we lived with one foot in Buenos Aires and the other foot in Italy, not really Leo, the first day he arrived in Treviso he said that he finally felt at home.

The family that remained on my mother's side was more interested in sharing the inheritance than being a united family. Although they always put my father on a pedestal, my mother and Leo and I were jealous of how Teresa and Juan treated us and how close the five of us were, I didn't see the difference but all that resentment came out. light when my mother ceased to exist. The mind and character of my grandfather Juan was not seen that he was sick. There I realized that I didn't want to stay in Argentina. All those places that I visited with my parents, the house where I grew up made me see their absences, I had returned to Buenos Aires after high school and was studying at the University of Palermo. Once again I had to be careful with who I spoke to, my mother told me; “You got used to Italy that you could say what you wanted.” This time it was she who was afraid for me. Some of my classmates had changed their attitude after I told them that my father was missing.

In January 1997, Leo and I moved back to Italy. The only thing that hurt me was leaving behind my childhood friends, my two grandmothers and my aunt Yoko. But they supported our decision to leave Buenos Aires again. We saw my obaachan (as we called my grandmother Ikuko) every summer in Italy, living in Treviso again was breathing a sigh of relief.

my sense

What happened to my father? How it happened? What or who were you thinking about? What was your last thought? Where is he buried? My old man was so persevering and optimistic that I'm sure he never gave up, waiting for the day he would be able to hug my mother again. Maybe he understood that there are people who cannot be reasoned with. He loved the art of creating, using words, chaining them into groups and communicating with others.

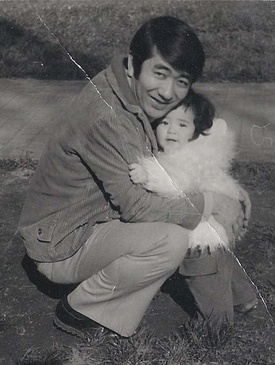

Will I ever have those answers without needing to guess? I sincerely hope so, in the meantime I have seen that the outside world does not provide them to me, I took the introspective path. What I manage to process internally, I express through my paintings. Painting my father's portraits confirms to me that I didn't imagine him, that he was here, that he was real, made of flesh and blood. It allows me to remember that our outings to Rivadavia Park or the Buenos Aires Zoo on his shoulders really happened. It allows me to see him again walking on his hands with my mother laughing near the seashore. It wasn't a dream.

The portrait on canvas of my old man becomes the witness: I can look into his eyes for a few moments like a flashback , it is not just that worn out black and white photo that is paraded on the flag in the marches of the Disappeared of the Japanese Collective but a human being who fought for a better world. By simply creating a new image out of nothing, I can provide an answer to the actions of his murderers who tried to erase his identity, who hooded him and exchanged his name with a number like the other 30,000 missing people. .

Oscar Takashi Oshiro, my father, was not NN (nomen nescio), nor was he a number. The disappeared were murdered for their ideas, their values, their convictions, their projects, above all for their humanity, something that the genocidaires could not and cannot understand. The sadistic torture, their methods of killing, the conditions of the detainees in the clandestine detention centers, the theft of newborn babies and all the other atrocities committed are proof that they had no humanity or conscience whatsoever. They were people classified as such only by genetic material, but they lacked all those qualities that make a person a human being: compassion, empathy, the ability to recognize good from evil, they did not develop much mentally, they knew only violence.

The fact that those who are in prison ask to be pardoned or released, or consider themselves “political prisoners,” shows that they have no remorse and still continue to justify their aberrant actions.

Two years ago my studio had been filled with black and white photos, like those seen on the flag of the Association of the Disappeared of the Japanese Community in Argentina, sketches , portraits with different materials. My children would come to the studio and ask me who those people were. I told them a little about each of them and what they did and I also logically told them about their grandfather.

My oldest son Dylan, he is 12 years old, is the one who physically resembles my father the most. I told him about the story of my father and his family in Okinawa, about how much they worked to have a better life, about my father's fight to defend the workers, about the love, loyalty and commitment that my mother had towards me. father. Dylan was proud to be the grandson of Oscar Oshiro and Beba Bresolin. At 10 years old, Logan didn't want me to leave him for 20 days while I went to Buenos Aires: I explained to him that it was something I was doing for his grandfather and he let me go. My youngest son, Drake, recently turned five. He was present at the Library of Congress and for a week he helped passing screws to Juan, the man who put together the installation for the exhibition of my paintings. Drake asked me very interested what we would do with all the portraits while he jumped around the exhibition playing with balloons that had been given to him.

For a whole year I looked at the faces of the missing and imagined what they really were like. Some photographs were so blurry that I had to imagine their features, like that of Jorge Nakamura, who disappeared on May 6, 1978 at the age of 21. When I finished his portrait after many tests, I hung it on the wall and that painting gave me strength to try to express each person's personality. The 17 missing Nikkei were no longer anonymous individuals. When I had to leave the paintings at the exhibition because I had to return to the United States, where I currently live, it was like having to say goodbye to my new friends. My job today, or our job, which is collective, is to remember each one of them, to be living proof that they existed, and will always be in our memory.

© 2017 Gaby Oshiro