The Japanese American Committee for Democracy (JACD), a New York-based social and political group of the 1940s, has been effectively ignored in the history of Japanese Americans. The JACD held rallies to support the American war effort in World War II, helped Japanese Americans in New York to find jobs and housing, and provided a forum for like-minded Issei and Nisei to meet up and socialize. Their monthly publication, the JACD Newsletter, offers historians a vital resource on what was going on in Nikkei circles in New York—especially during the early months of 1942, when the city was home to the largest “free” community of Japanese Americans on the mainland.

The JACD was first founded in New York in the period before the outbreak of war. As we know from Eiichiro Azuma’s Discover Nikkei article on New York’s Japanese, the local community, largely composed of Issei, remained dominated in those years by consular officials, Japanese businessmen, and employees of Japanese firms soldily pro-Tokyo in sentiment. Japanese news predominated in the community’s semiofficial organ, the Nichibei Jiho. The English-language Japanese American Gazette, which started out as the Jiho’s English page before spinning off into a separate journal in 1940, devoted so much space to propaganda extolling the Japanese puppet state of Manchukuo that it was clearly influenced (and possibly subsidized) by Japanese officialdom.

Yet as Japan and the United States drew closer to open conflict, dissident community members mobilized. Hoping to counteract pro-Japanese forces within the community and protect members’ rights in case of war, members of a circle of Issei artists and militants joined forces with activist Nisei such as journalists Larry Tajiri and Tooru Kanazawa to form the Committee for Democratic Treatment for Japanese Residents in Eastern States. The first director was Reverend Alfred Akamatsu, the young Japan-born pastor of New York’s Japanese Methodist Church. The group remained largely dormant during its first months. However, in the wake of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941 and the U.S. entry into war, the situation changed drastically. New York’s Japanese consulate closed and over a thousand prewar businessmen and community leaders were arrested as potentially disloyal and detained at Ellis Island by the Justice Department.

These events left a void in ethnic leadership. Progressive activists responded by calling a public meeting in the days that followed, which 150 people attended. The meeting gave rise to a transformed organization, dubbed the Japanese American Committee for Democracy (JACD). The new organization elected a chairman, Thomas Komuro, established a structure of 6 subcommittees, and began a regular newsletter (Larry Tajiri edited the first issues, before he returned to the West Coast). An all-star collection of progressive celebrities, including Pearl S. Buck, Albert Einstein and Franz Boas, signed on as advisory board members.

The Committee’s first priority was to organize social service work within the Japanese community. The Vocations and Welfare Committee provided information to those thrown out of work by the closure of Japanese businesses about collecting unemployment insurance, and made inquiries into job aid from churches and government. Under the leadership of Rev. Akamatsu, the JACD organized a social study of the New York Japanese community, to determine where aid was most needed. The JACD also engaged itself in protesting discrimination against Japanese Americans in New York, which had by far the largest “free” Nikkei community on the US mainland. In mid-March 1942, the JACD sent a letter to Attorney General Biddle asking him to create a federal agency to create jobs for Japanese Americans unable to find jobs because of suspicion by potential employers.

At the same time, to encourage Nisei participation and strengthen community morale, executive board member Toshi-Aline Ohta, a biracial Nisei still in her teens who was active in artistic circles, organized various programs. In June 1942, for example, Ohta hosted a tea party for Nisei girls to encourage them to become active in the war effort. She also helped arrange dances and other entertainment, and ultimately recruited musicians such as Leadbelly and Woody Guthrie to perform at JACD dances. After several months, she gradually withdrew from the group, and in 1943 she married the folksinger Pete Seeger.

Meanwhile, under the direction of a circle of seasoned Issei activists, notably Executive Secretary Yoshitaka Takagi, the JACD mobilized as a political action group with ties to the Communist Party. Although the number of actual party members in the JACD is a matter of dispute, and the group’s militants were by no means simple-minded hacks, their platform and strategies were shaped in significant ways by the Party and its wartime program of total victory over fascism. This was a double-edged sword as far as the Committee was concerned. On the one hand, the emphasis on the larger anti-axis struggle encouraged group members to look beyond their own group interests in support of democracy. On the other hand, the JACD’s doctrine of full support for the war clashed with its recognition of the injustice done to West Coast Japanese Americans.

During the JACD’s early weeks, there was no contraduction between its ethnic group status and support for the war effort. JACD leaders made patriotic statements endorsing America’s war effort and organized a blood drive to aid soldiers. Group members provided government agencies such as the Office of War Information with translators, record albums and other materials.

However, President Roosevelt’s issuing of Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942 flung JACD leaders into a dilemma of their own making. Immediately after the Order was issued, the JACD responded with a formal letter of support to the government. As the February 23, 1942 issue of the JACD Newsletter reported, “In effect, our letter stated that while we realized that the majority of Japanese Americans are innocent, at the same time we recognized the possibility of fifth columnists working in their midst. As our committee is pledged to the full support of national defense, we offered to back whatever action the government deemed necessary to protect the strategic coastal zones and vital industrial areas.” Conversely, in May 1942 JACD members attending a conference of the pro-Communist action group American Committee for the Protection of the Foreign Born approved a resolution calling for the setting up of loyalty boards for “Germans, Italians, and Japanese” which could determine individual guilt, and the group opposed Senator Tom Stewart’s bill to intern all persons of Japanese ancestry in the United States.

The fundamental contradiction between the JACD’s policies of opposing discrimination and giving full support to the government was laid bare in June when Socialist Party leader Norman Thomas—himself a leading rival of the Communists—organized a meeting through the Post War World Council to protest Executive Order 9066. At the meeting, Mike Masaoka of the Japanese American Citizens League (which had launched its own policy of collaboration with the government) stated that the treatment of Japanese Americans was “a test of democracy” and warned “If they can do that to one group they can do it to other groups.” With Masaoka’s support, Thomas introduced a resolution calling for the establishment of hearing boards to determine the loyalty of the “evacuees” and warning against the “military internment of unaccused persons in concentration camps.” Although this resolution resembled the one the JACD had just approved in May, a JACD delegation offered a counter-resolution endorsing the government’s claim that “military considerations made necessary the evacuation of all Americans of Japanese ancestry from certain areas on the West Coast,” and supporting all measures to help ensure victory. While the JACD resolution was handily defeated, it reduced the momentum for Thomas’s, which passed only narrowly. In a letter to the government shortly after, JACD secretary Yoshitaka Takagi formally disavowed any protest of EO 9066 as divisive.

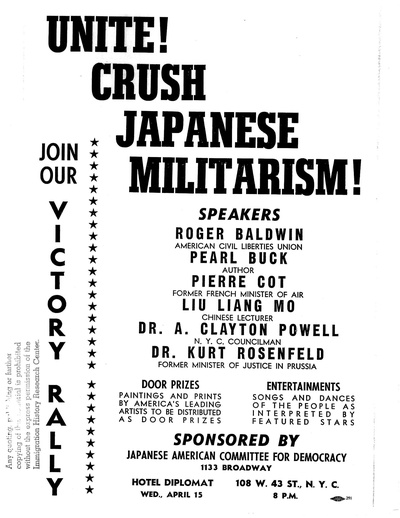

Even as it sought to quell criticism of government discrimination against Japanese Americans, the JACD turned its attention to a large victory rally designed to promote “the end of all racial discrimination and the establishment of a mighty People’s Front against fascism.” According to the May 5, 1942 JACD Newsletter, the event was a great success. None of the speakers, apart from Pearl S. Buck, discussed the discrimination facing Japanese Americans, let alone denounced the injustice of the government’s action. Rather, the keynote speakers, African American leader Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. and Chinese musician Liu Liang Mo (who was also a columnist for the African-American newspaper Pittsburgh Courier), focused on equality for their respective groups and on friendship for the Soviet Union. The JACD continued the same policy in June 1942 when its invitation to join in New York City’s Victory Parade was rescinded by Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia on the absurd pretext that it would lead to violence against Japanese American marchers. Although the JACD called the Mayor’s act “ill-advised,” its leaders urged acceptance of the decision in a spirit of unity.

By late fall 1942, the expulsion and incarceration of Japanese Americans was complete. The JACD was thus freed of its burden of defending the policy. While it did not call directly for the closing of the camps, which would constitute criticism of the government, it focused on encouraging resettlement. In its February 1943 Newsletter, the JACD invited WRA Director Dillon Myer to a forum on “Japanese Americans in the victory program.” A positive program on Japanese Americans, the JACD claimed, was essential. In the following months, JACD members volunteered their services to the government as liaisons in resettlement, and worked to find sponsors and housing so that internees could leave the camps. In coalition with the National Maritime Union, JACD leaders lobbied the War Department and the WRA to speed up the release of Japanese American merchant seamen from the camps.

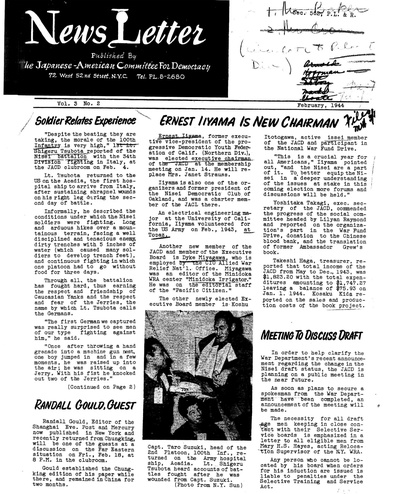

Meanwhile, as young Nisei began leaving camp and migrating to New York, they turned to the JACD. Its office became a gathering place for the young resettlers. A number of Nisei who had been active in political groups on the West Coast, including Eddie Shimano, Kenji Murase, Dyke Miyagawa, and Nori Ikeda Lafferty, resettled in the city and became active in the JACD. In the face of this development, the Issei leaders of the JACD formally resigned to let the new generation assume responsibility. Ernest Iiyama assumed direction of the organization, and his wife Chizu Iiyama took a leading role in producing the JACD Newsletter. In addition to its support for resettlement, the JACD embraced interracial struggle for equality, reporting on efforts to fight lynching of African Americans in the south, and lobbying on behalf of the successful repeal in Congress of the Chinese Exclusion Act. The JACD also issued statements denouncing episodes of Japanese barbarity and opposing peace negotiations with Tokyo before victory over Japan. The JACD Arts Council, formed under the leadership of Yasuo Kuniyoshi and Isamu Noguchi, organized art shows and entertainment as well as issuing political statements. In fall 1944, the JACD joined with other racial groups in a rally supporting the re-election of President Franklin Roosevelt. In the last months of World War II, the JACD helped sponsor the Japanese People’s Emancipation League, a Japanese resistance organization that operated in China in assocaition with the Chinese Communist Party.

Once World War II ended, the JACD began to fade away. Its membership was consumed by the tasks of remaking their lives, and the JACD faced competition from the fledgling New York chapter of the JACL. In 1948, the remnants of the JACD reorganized as the Nisei for Wallace (aka Nisei Progressives) to support Henry Wallace’s third-party presidential candidacy. The Nisei Progressives continued into the early 1950s. However, like many other wartime political groups, it ultimately fell apart, a victim of postwar equality and McCarthy-era political withdrawal. A few JACD leaders, such as the Iiyamas and Toshi Ohta Seeger, continued their activism elsewhere. For others, such as Motoko Ikeda and Kazu Iijima, their JACD experience helped served as a guide when they became involved later in life with a new political organization, Asian Americans for Action.

* Portions of this article are drawn from Greg Robinson, "Nisei in Gotham: Japanese Americans in Wartime New York," Prospects: An Annual of American Cultural Studies, Vol. 30 (2005), pp. 581-595.

© 2017 Greg Robinson