Over the past several years, I have been engaged in large-scale research on the remarkable and largely-unknown history of ethnic Japanese in Louisiana, especially in the cosmopolitan city of New Orleans. (Readers of Discover Nikkei should check out the groundbreaking series on the subject by Anna Kazumi Stahl and Midori Yenari). One particularly noteworthy aspect of the story of Nikkei in Louisiana in the first half of the 20th century is the record of their participation in sports, especially at the college level. To be sure, there were only a handful of individuals involved: with such a tiny and scattered prewar ethnic Japanese population, there was no counterpart to the all-Nisei semipro teams that dotted on the West Coast, whether the legendary Vancouver Asahi or Los Angeles Nippons baseball teams, or the Seattle basketball league founded by the Japanese American Courier newspaper. Still, not only were the achievements of the Japanese athletes in Louisiana impressive in themselves, but they testified to an overall level of social acceptance and inclusion that formed a vivid contrast with the situation of West Coasters.

Just exactly when Japanese athletes first began playing in Louisiana is not entirely clear. According to contemporary newspaper accounts, in spring 1905, Shumza (AKA Shumzu) Sugimoto, a Japanese baseball player who had played for the African American baseball team Cuban Giants, was offered a tryout with the National League champion New York Giants by legendary manager John J. McGraw. Had Sugimoto been selected for the team he would have become the first ethnic Asian major leaguer. However, after being rejected (on racial grounds?), he announced that he would spend the season playing with the Creole Stars, an African American team in New Orleans. There is no other documentation about Sugimoto, his immigration or his baseball career. Citing this fact, some baseball historians have cast doubt on the accuracy of the story.

What is certain, however, is that various Japanese did compete in sports in Louisiana. In 1922, Shizuka Nakamura, a dental student at Tulane, joined the school’s wrestling team. In 1937, Roger Yawata, a former East Bay all-star in his high school days in Oakland, California, joined the football team at Loyola University as a guard. In 1938, one S. Yamate competed in the New Orleans open winter tennis tournament. Three years later, the New Orleans Lawn Tennis Club hosted the annual city tournament. Hajime Naka and George Masuda each competed in the individual matches, and the two teamed up for the doubles. In 1943, Audubon Park was the site of the Southern A.A.U. swimming and diving championships. Thanks to financial support from Nisei benefactor Earl Finch, a swimming team from the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, training at Camp Shelby in Mississippi, was able to get leave and travel the 112 miles to New Orleans to compete. Led by Takashi « Halo » Hirose, who had been national champion in the 100 meters in 1941, as well as Charlie Oda and Charlie Tsukanao, the Nisei swimmers competed in various events, and walked away with the first-place trophy.

Amid this company, there were two outstanding Nisei athletes. The first was Herbie Hiroshi Mashino. Born in Kansas City in 1916, he grew up in Oklahoma City and Shidler, Oklahoma, and he attended the Oklahoma Military Academy (now Rogers State University). There he became known as a featherweight boxer. In April 1936 he won the Missouri Valley bantamweight title. The next year, he won the Oklahoma A.A.U. featherweight title by defeating William Tiger, and travelled to Chicago to participate in the Golden Gloves amateur boxing tournament, where he went to the finals before being defeated by Johnny Estrada. He also boxed in that year’s tryouts for the U.S. Olympic boxing team, also held in Chicago, but failed to make the squad.

In 1937, Mashino enrolled at Centenary College, a Methodist institution in Shreveport, Louisiana, where he majored in History and joined their boxing team, the Centenary Gents. The appearances of the “American-born Japanese” were covered in multiple newspapers from the region. In his first season he won a TKO in a match with ace bantamweight Bumps Gormley. While he lost a big bout to Loyola’s Sewele Whitney, the A.A.U. Champion, in February 1938, Mashino won a great victory the following month when he defeated Tommy Hand, a two-time Oklahoma Golden Gloves champion. As a newspaper account described it, Hand “found Hiroshi Mashino, clever little Japanese and former O.M.A. star, too fast and too tricky. Mashino had the little Indian on the retreat most of the way, and in the third round was dealing out considerable punishment. Hand was game, but no match for the clever Gent.”

After leaving Centenary, Mashino did postgraduate work at Oklahoma A& M University. In December 1941, he had just completed a national defense course and was set to work at an airplane plant, but was arrested as a “dangerous Japanese” and jailed with five other men. In 1942 Mashino joined the Army Air Corps. After the formation of the all-Nisei 442nd Regimental Combat Team, he was assigned to 2nd battalion, G Company. At some point he was promoted to PFC. In 1944, he was assigned to Fort Sheridan, Illinois and returned to boxing. In the South Side Chicago Golden Gloves, he knocked out George Holt, and then beat Sgt. Joe Kiado. In another bout, he knocked out Bill Danzy. There is no record of Mashino continuing his boxing career after World War II. In later years he worked in the financial management division of the Marine Corps. He died in Maryland in 2004.

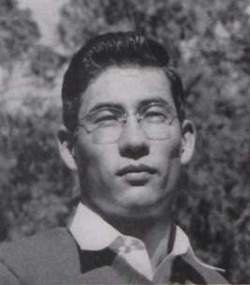

An even more celebrated Nisei athlete was Joe Nagata. Born in Montgomery, Alabama, in January 1924, he was the son of Yoshiyuki Nagata, a Japanese immigrant, and his Irish-American wife Edith. Joe grew up in Eunice, in Louisiana’s Cajun country, where his parents ran the Eunice Market, a produce store in town. Nagata starred as a halfback and fullback on Eunice High School’s football team, and in fall 1941 was named to the all-Southwest team. Just days afterward, the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor launched the United States into World War II. The following Wednesday, while carrying a load of produce, the elder Nagata was arrested by FBI agents and held overnight, while his car and cash were seized. FBI agents then visited the family store, which was forced to close for three days during the investigation. While agents confiscated a short-wave radio, Mr. Nagata was permitted to return, and the store then reopened as usual.

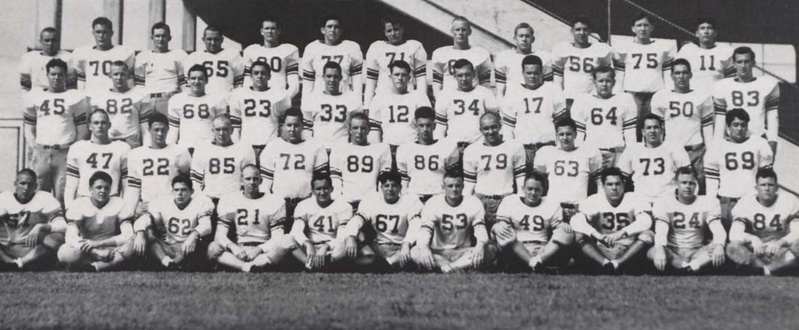

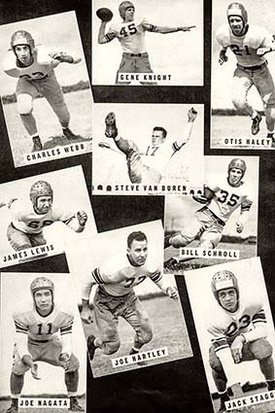

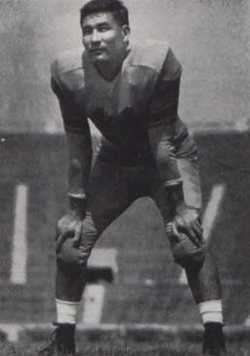

After winning a football scholarship to Louisiana State University, Joe Nagata enrolled at LSU in 1942, and soon joined the LSU football team, then under the direction of coach Bernie Moore (future major league baseball star Alvin Dark was Nagata’s teammate). At 165 pounds, he was too slight for fullback. Posted at halfback and wingback, Nagata played well enough to win his letter. On November 7, in a game against Fordham University at the Polo Grounds in New York, he caught a pass and scored a touchdown.

Nagata began the 1943 season with a hamstring injury, which limited his effectiveness through the balance of the fall. By January 1944, when LSU faced off against Texas A&M in the Orange Bowl in Miami, Florida, he was healthy. Placed as fullback in LSU’s Notre Dame Box formation alongside Steve Van Buren (later a Hall of Fame pro with the Philadelphia Eagles), Nagata’s running and handoff skills distracted the defense, and he helped LSU to a 19-14 victory. In 1944, he enlisted in the 442nd Regimental Combat team and participated in the Po Valley Campaign in Italy. He won eight medals for his military service, including the Bronze Star and the Infantry Combat Medal.

After the war, Nagata returned to LSU, and played again on the football team under the leadership of future NFL great Y.A. Tittle. Meanwhile he met Jen Brown, whom he married in 1949. The couple would have three children. After receiving a degree in Agriculture from LSU in 1951, Nagata returned to Eunice. There he became a high school teacher and football coach at Eunice High School and St. Edmunds. In 23 years as head coach, Nagata won 142 games, and his teams twice reached the state finals. Nagata was elected to the Louisiana Sports Hall of Fame. Following Nagata’s death in 2001, Eunice High School named the Joe Nagata Memorial Jamboree in his honor.

Louisiana would continue to feature Japanese athletes even after the war years, including the weightlifters Walter Imahara and Ted Yenari; footballer Scott Fujita of the New Orleans Saints; and numerous practitioners of competitive sports. A more exhaustive study may prove useful in assessing their contribution.

© 2017 Greg Robinson