Hidden Histories Trailer from Full Spectrum Features on Vimeo.

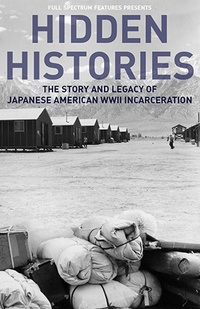

As the years have passed, the importance of the Japanese American story as a part of the larger American historical tradition has become more commonly taught, shared, and known. However, what is lost in the changing contextualization of a peoples’ history is the personal, more individual aspect that is so vital to our understanding of groups at a certain time, and at a certain place. Concerning the Japanese American incarceration experience, people today often find themselves in danger of alienating themselves from injustices, and possibly even forgetting its impact on the lives of over 120,000 people.

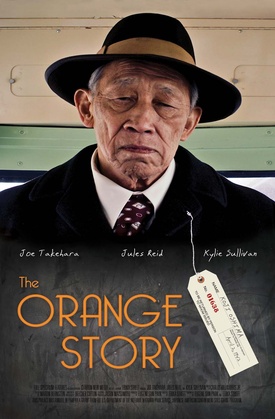

This long and varied history spanning from World War II to modern day is what the collection of short films, Hidden Histories: The Story and Legacy of Japanese American WWII Incarceration, strives to encapsulate; its featured creators present five short films each with their own unique time period, subjects, and artistic styles, all the while maintaining the thread of an overarching Japanese American story. I was lucky enough to experience the films for myself, and even luckier to interview two of the producers behind the short film and transmedia educational project, The Orange Story, Eugene Park and Jason Matsumoto.

* * * * *

What made you decide that this was an important story to tell? Was there any real life story that particularly inspired you in the production of this short film?

Eugene Park (EP): Cinema plays an important role in reifying certain moments in our nation’s history as “defining,” “formative,” “quintessential,” etc. I wanted to tell this particular story because it addresses an important part of our nation’s history that is not well understood or considered by most Americans. History teachers are often blamed for this, but I actually think that’s unfair. This history is taught in schools and the basic facts are readily available. The problem, in my view, is that this history is not valued as a central part of American history. This is entirely a problem of how this history is regarded; it’s not a problem of a lack of information. My belief is that when people start seeing the incarceration as something that we did to fellow Americans, then this history will be better integrated into our sense of identity as a nation. And that has always been the point of The Orange Story—to show the main character Koji, first and foremost, as an American. This is not a factual point, but an emotional one. It’s a matter of seeing Koji as “one of us” as opposed to “one of them.”

Do either of you have any personal connection to the story depicted in the film (i.e. family history of incarceration)? Did you learn anything surprising or interesting during production?

EP: My family is Korean, so we do not have a direct connection to this history. But as an Asian American, I identify strongly with the perpetual sense of “otherness”—i.e., feeling like no matter where you were born, what your passport says, where you live and make your home, certain people just won’t treat/view you as a fellow American.

As far as things I’ve learned from this project, it’s hard to capture that in a just few sentences. I’ve learned so much about this history and its legacy, and I keep learning new things every day. Perhaps the most inspiring thing I’ve learned is how resilient the JA community has been throughout all of this. Along the same lines, one of the most interesting thing I’ve learned is that there are fierce tensions—even today—within the JA community about how to understand and respond to the incarceration. There’s a lot at stake here, and everyone is motivated by the same desire to get it “right.” But there’s a lot of disagreement over what that should look like.

Jason Matsumoto (JM): Yes, both sides of my family endured incarceration. My immediate family came from places like Stockton and Terminal Island, CA. They were farmers, owned laundry and hotel businesses, worked in the canneries, and even worked the coal mines in Utah (before moving to Terminal Island). My grandfather on my father’s side was a kibei who was drafted into the MIS. My grandmother on my mother’s side recounts that her high school graduation took place in a Santa Anita horse stall. My grandfather on my mother’s side was months away from graduating Berkeley with an optometry degree only to find that the record was wiped as incarceration took shape (he re-started the entire degree in Chicago and became a central community figure through his successful optometry practice). They ended up in Rohwer, Gila River, and Tule Lake. Each of them found a path to Chicago and eventually made the city their home. I’m constantly in awe of their resilience.

So much learning! Part of my role on the project is to travel with the film when presenters want to engage in conversation through Q&As, talkbacks, and panel discussions. I’ve learned a lot of facts and nuances about the incarceration as I’ve traveled. I’ve met so many amazing people along the way—people who have dedicated their lives to telling this story, and stories of Asian Americans in the U.S. for the purpose of diversifying historical perspectives.

Something that has surprised me: the film’s ability to generate conversations amongst JA families. Over and over, descendants of incarcerees have expressed that their parents and relatives never spoke about their imprisonment—likely due to the trauma embedded in the recollection of their experience. But at the end of a screening, many people find a safe space to share—offering stories they’ve never heard about their own families and passing on an inter-generational legacy. It’s a beautiful moment of self-discovery.

The short film is intercut with some actual photographs of Japanese American establishments, people, and historical events; what artistic or emotional effect were you striving for through this choice?

EP: The main goal behind this choice was to ground an otherwise fictional story in reality. We wanted to use the power of narrative film to create empathy and compassion for a single individual. But we also wanted his story to carry a broader significance, and to continually remind the viewer that what happened to Koji was not an isolated incident, but something that happened to over 100,000 people.

JM: Adding to Eugene’s comments, the primary source documents that exist in the film aid in our ability to transition a student from the film’s fictional world into the educational website. The site neatly packages facts, figures, oral histories, and additional primary source artifacts. Our overarching goal is educational impact and the website has been thoughtfully built to act as an extension of the film—so think of the film as a portal of empathy that leads to engaged historical study and discourse. This site won’t be live until late October of 2017, but here’s the future URL: www.TheOrangeStory.org.

Are there any other stories that you are particularly eager to bring to the screen in the future?

EP: I’m interested in and produce a broad range of stories, but Asian American historical narratives are my true passion. The Fred Korematsu story is at the top of my list. I’d love to do a film about Richard Aoki. I’ve also written a screenplay about the killing of Vincent Chin that I hope to produce one day.

JM: One gap that I see within the incarceration narrative is stories about the Chicago resettlement, which was the largest resettlement city outside of west coast returnees. There is a rich fabric of history in Chicago and the overall narrative of Japanese American incarceration will benefit from expanding [its] focus.

Who were you hoping this film would reach, and what relevance does it hold for audiences today?

EP: Our goal has always been to reach beyond the JA and Asian American communities, so it was important for us to create a “universal” story with wide appeal. As we continue to screen the film for a wide range of audiences, we’re finding that it resonates in many different ways. Some folks connect the film to “travel bans” and other policies of the current administration. Others connect it to entirely different issues and themes. Ultimately, though, I hope that all audiences see this as a cautionary tale about what can happen if we compromise our principles and ideals in the very moments when we most need to uphold them.

JM: This is an important question for us and we certainly haven’t found the magic formula for engaging people who may not want to hear about this story, [its] lessons and [its] implications on civil rights. However, and especially in a moment in history where the divide between communities with opposing views seems so great, we are here to show people that this is not a Japanese story, not a Japanese American story, not an Asian American story—but an American story.

* * * * *

Film Screening and Discussion—Hidden Histories: The Story and Legacy of Japanese American WWII Incarceration

September 30, 2017

Japanese American National Museum

Hidden Histories is a touring program of five short narrative films about the World War II incarceration of Japanese Americans. Each film tells a personal story that dramatizes a different aspect of this history.

Hidden Histories commemorates an important chapter in American history at the same time that it serves as a cautionary tale; although the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians declared in 1982 that the Japanese American incarceration was “motivated largely by racial prejudice, wartime hysteria, and a failure of political leadership,” our nation is at risk of repeating those mistakes. Hidden Histories reminds us of the profound cost of abandoning our ideals of an inclusive society and equal protection under the law.

© 2017 Japanese American National Museum