Do you also feel that something about Isamu Noguchi’s mixed-race identity shapes his sociopolitical worldview?

(Photo from Wikipedia.com)

I think the time that he spent in Indiana was really formative. This heartland experience, and he’s in the presence of this industrialist who has various farming equipment manufactured, he runs a newspaper so he sees this guy essentially as the personification of the American businessman.

And also he’s learning about the founding fathers and he’s definitely aware of the farming cycle. And he’s getting a mix of agrarian culture but he goes to New York and experiences it becoming the business center of the world. So he very much becomes an American very quickly and his political leanings, I think he visits Japan once in 1930. It’s a very unhappy visit. Somehow the news that Noguchi is en route to Japan makes its way to his father and his father asks when he enters Japan that he doesn’t use the name Noguchi. Somehow on the train he meets a reporter, just a really random meeting and his father catches wind of it. When Isamu gets to China he stays for eight months before deciding to go to Japan. He meets his father and his father’s family very briefly. he’s given a very cool reception. He ends up spending a lot of time with his uncle who takes him under his wing and houses him in Tokyo, and we have a portrait of his uncle.

So he was more sympathetic to him?

Absolutely. And his uncle actually liked and embraced his mother, so Isamu knew he felt secure with this guy. Because he uncle accepted that he was half Japanese and half Western.

And the reason for not using “Noguchi” was just because the father was saying do not use my name?

There’s some different tellings of it but it’s partly because of his new family, it would bring shame on them.

Messy.

Yes it’s very messy, it’s hard to condense his biography. But during this time he goes to Kyoto and when he goes there he says he wants to study ceramics and pottery but he wants to study with somebody that makes knock-offs. So he wants to learn how to perfect mimicking, like ancient Japanese ceramics. He becomes interested in nahanewa ceremonial ceramic dolls that are often put on funerary shrines in Japan. So while he’s in Kyoto he works with a potter there, and he just immerses himself in work. This is the activity that he always returns to that he’s most comfortable with that can help him forget whatever pain is going through in his life. He really thrives in the studio and setting his mind to a task. There’s a lot of interpretation to that but you’ll see it, in his own written remarks, especially after the Poston episode he comes back to New York and finds a studio that’s a live-in, work-in studio and he’s able to just immerse himself.

He is active in artist communities in New York in the late ’30s. Some of his best friends are Arshile Gorky who was an outcast kind of because he’s a European and he kind of creates an identity for himself. The biographers go into their commonalities a lot. But in summer 1941, he and Gorky and Gorky’s wife and a friend drive to the West Coast. Gorky has a show set up there, Noguchi has slim pickings in New York. He’s just accomplished his most major project in 1939 which is the stainless steel freeze at Rockefeller Center. At that point it was the largest stainless steel sculpture in the world, it still could be.

So he and Gorky decide to try their luck with a trip to the West Coast. I think Gorky goes to San Francisco and Noguchi spends a little bit of time there, and he also manages to get a ticket to Hawaii from the Dole Pineapple Corporation. He did manage to set up a museum show at the Honolulu Museum.

In 1940 he has the show there and when he and Gorky are in San Francisco I think that’s kind of the beginnings of him getting into a show at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. In the meantime Noguchi goes to Los Angeles and during that time, he’s trying to work his network, meet new people. He somehow comes into contact with the actress Ginger Rogers. She commissions a portrait from him and she sets up a studio outside of her house for him to work in.

So this essentially sets the stage for December 1941, the bombing of Pearl Harbor. Noguchi’s supposedly driving to San Diego from Los Angeles when he hears the news–he returns to Los Angeles. And he gets in touch with as many Japanese and Japanese American organizations as he can. So aside from this commission from Ginger Rogers and a few others, he doesn’t have a lot going on so he kind of dives head first into activism. And he was part of activist organizations on the East Coast before that but never a driving member. He has this natural aversion to groupthink.

So he co-founds the Nisei Writers and Artists for Democracy and he gets immersed in a number of projects. They want to convey what commonalities the Japanese and Nisei have with Americans in the United States. They’ve obviously come to the United States to make a better living for themselves. The story of the 20th century is that capitalism needs workers and they’re always willing to short sell one worker for another, and that is the story of why the Japanese are in America and it is because they were seen as cheaper labor. So naturally when Pearl Harbor is bombed, the Japanese immediately become the enemy. Part of this is fueled by the butting of heads or jealousy that the Japanese are taking jobs away from Anglo Americans living on the West Coast. So this group that Noguchi co-founds, they set about writing a lot of radio scripts, they want to show that the young Japanese are as American and just as anti-Fascist as you and I. They escaped or they left willingly, a culture that was becoming more and more militant from the 1910s to late ’30s.

And were these broadcasted?

I think one was. Noguchi was not totally involved, he was more of a spokesperson, he was happy to lend his name and contacts to the effort. He would contact whoever he could within the government and different activism circles. There was a push to do a documentary, filming the evacuation. He thought it would be valuable for people to see the pain and struggle that was going on.

Meanwhile he’s also working his connections, he wants to get very involved. Once the Executive Order is put into place and it’s clear there’s going to be a mobilization of putting the Japanese Americans into the camps, Noguchi who hasn’t really had much connection with the community up to this point–it’s always been limited and hesitant–he sees this as kind of an opportunity. It’s with the best intentions that he’s going.

He hears of this guy John Collier who’s the Commissioner of Indian Affairs. He led the rally to make Indian reservations a more humane place, and he’s kind of like a figure within the government that wants to be more involved in the evacuation of the Japanese Americans and provide the same service. So somehow Noguchi meets this sympathetic ear and he pitches the idea that, “If I can go into the camp I can do good there. I can hopefully lead art classes, I can lead people think more about their Japanese heritage and their American identity.” Because he does see the Japanese in the camps as identifying as American for the most part but while he’s in the camp he does see there are various levels of Americanness. He sees some of the grandparents and parents not speaking English, some of them cling to their traditions, and in a way that makes their children and grandchildren uncomfortable. Kids that grew up listening to American radio have essentially no commonality with the former culture. So he wants to find a way for both of these disparate groups within the camps to maintain an identity as both Japanese and American but first and foremost as anti-fascist. He’s aware that at the same time a lot of these families are put into the camps a lot of their sons are being drafted and going to war to serve the United States. So he’s trying to satisfy all these different elements.

It’s a lot for him to take on.

Yes absolutely. He’s seeking out quotes for ceramics and art classes and he’s also contacting some of his friends. He knows Langdon Warner, a scholar and curator from Harvard University. He and Warner talk about arranging exhibitions in outside world so we can humanize the interns in the camps. He also has friends like Yasuo Kuniyoshi who talk to him about coming in as an outside professor and teaching classes for him. But once Noguchi is immersed in the camp, he sees that he is just as disconnected as he expected he might be. He’s kind of viewed suspiciously by the population of the camp.

How so? That he was a volunteer?

Some people think he’s a government mole. But outside of that he’s kind of an outlier.

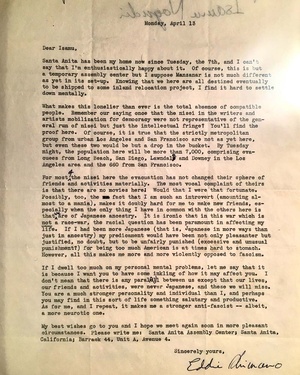

“For most of the nisei here the evacuation has not changed their sphere of friends and activities materially. The most vocal complaint of theirs is that there are no movies here. Would that I were that fortunate.”

And there’s a great letter from one of his friends, Eddie Shimano. Throughout this whole lead-up going into Poston he’s in communication with people on the same educational level and these are activists that are well-educated and also kind of somewhat separate from the Japanese and Japanese American community: They’re all anti-fascist activists first and Japanese second or third. So Eddie Shimano wrote this great letter telling Isamu what he can expect, like feeling lost within the camp. “There’s no one to talk to about the things that I care about. I feel separate, it’s lonely, it’s hot during the day and it’s freezing at night.” Just the discomfort of the experience.

Noguchi is greeted with that even before he goes to the camp. It’s quickly apparent to him that he’s going to be miserable when he reaches the camp in May 1942. And within about six or seven weeks he’s already writing letters to his contacts, “Is there a way to get out?” Not only due to the physical realities but social realities within the camp. He sees these different schisms within the community itself. He’s writing to a couple of different friends in Santa Anita who were the editors and publishers of Doho Magazine, an anti-fascist journal. And he’s still got friends who are on the outside. They thought for sure he would be more valuable as a spokesperson on the outside than he would be on the inside. He had the best intentions. So whatever he was promised – support and budget – he’s writes to his friend John Collier: “What happened to what we were talking about? Can you pull some strings to see that we can follow through on our plans? But if this isn’t going to happen I’m not sure what use I am here since I’m an outsider.”

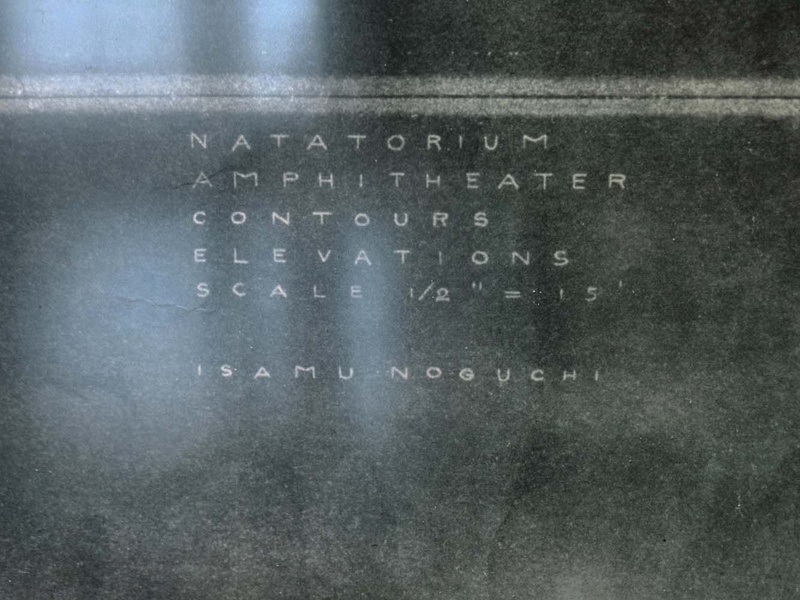

There’s a lot of idealism that went into him voluntarily interning in the camp. When he got to the camp, he came up with a design for the layout beyond the simple military barracks that are dehumanizing, these rigid rows of the same barracks. He wants to make a more humane place, like a playground. He wants to have a cemetery because it’s evident that life is going to continue and that means death is an inevitability within the camp. And how can these people preserve the traditions of burial and other things within the camp? These are all we have, he’s never really able to follow through on these civic designs but they’re among his first real efforts in this area throughout his career. It’s a little ambitious for the time and the circumstances.

So the War Relocation Authority actually had approved him being given an artist budget?

We don’t have a record of what he was promised but we only have the follow through on his end. I think the interest was also not there within the camp. I don’t know if that’s partly because he was viewed with suspicion.

*This article was originally published on Tessaku on May 3, 2017.

© 2017 Emiko Tsuchida