On January 18, 1963, architect Minoru Yamasaki appeared on the cover of TIME magazine, his disembodied head floating amidst the neo-Gothic tracery, delicate tenting, and flower-shaped fountains of his own design.

The occasion was Yamasaki’s commission to plan the then-$270-million World Trade Center. The commission was made controversial, in the words of the TIME feature, by the contrast between the “dreadful flaws” critics found in the work of the “wiry, 132-lb. Nisei,” and the pleasure his work gave to the public with its “declaration of independence from the machine-made monotony of so much modern architecture.”

Yamasaki’s aim was to please the eye, avoiding both the ubiquitous glass box and the Corbusian concrete tower, TIME said, while assuring its readers that the “humble,” “courteous” architect had a core that was “all steel.”

* * * * *

The roots of Yamasaki’s toughness lay both in his stylistic battle for pleasure and delight—traced through details of his trips to India’s Taj Mahal, Europe’s Gothic cathedrals, and Kyoto’s Katsura Palace—and in a lifetime of discrimination.

Yamasaki grew up in a wooden tenement less than two miles from the Century 21 Exposition grounds in Seattle; moved to New York after receiving his architecture degree, having seen top Japanese American graduates passed over for jobs; and sent for his parents after the 1941 bombing of Pearl Harbor to save them from being interned.

Yamasaki, his new wife Teruko, his brother, and his parents all shared a three-room apartment in Yorkville for the duration of World War II.

Back in Seattle, Yamasaki’s father had been fired from his 30-year job at a shoe store after the bombing. The architect’s New York employer, Shreve, Lamb & Harmon, designers of the Empire State Building, took the opposite tack. TIME presents this as a bootstrap narrative for Yamasaki: “You are one of our best men,” the magazine quotes Richmond Shreve, “and I’m going to back you all the way.”

And yet Yamasaki still experienced discrimination. After the end of the war, he moved to Detroit, taking a job at Smith, Hinchman & Grylls. He looked for a house to rent or buy in the Detroit suburbs, but realtors told him that, because he was not white, he could not live near colleagues like designer Alexander Girard, in Grosse Pointe, or architect Eero Saarinen, in Bloomfield Hills. (He and Girard would later collaborate on a house in Grosse Pointe.)

Instead, Yamasaki bought an 1824 farmhouse in more rural Troy, Michigan, which he renovated to give a modern interior and “Japanese-style gardens.” Architectural Forum’s article on his house referred to him as “American Architect Yamasaki,” and the Detroit Free Press wrote, in 1959, “To Americans [he and Teruko] look Japanese but they’re not. They’re contemporary American.”

Whatever “serenity” Yamasaki found in the farmhouse, it was a choice made from necessity. An architect who defined American postwar style—as on the TIME cover in 1963—had been perceived as a threat just 20 years before. Despite a high level of recognition and success, he was still being forced to prove his all-American bona fides.

* * * * *

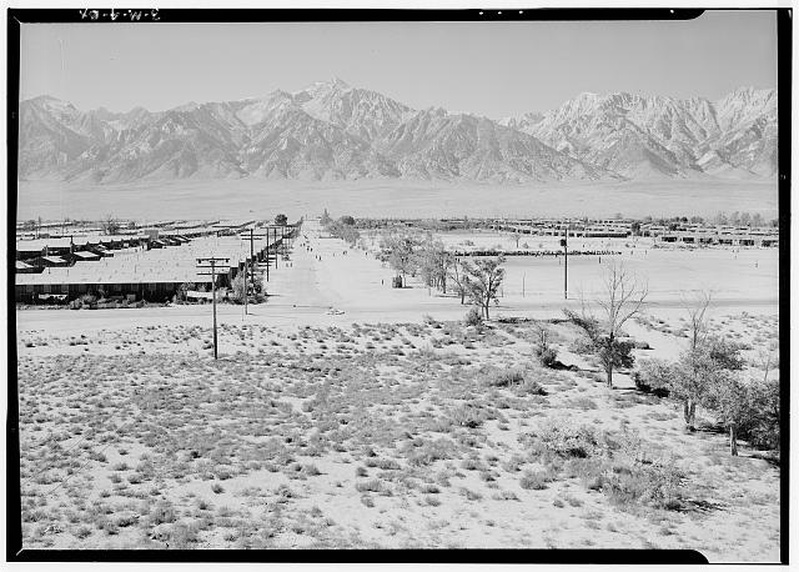

February 19, 2017, marks the 75th anniversary of Executive Order 9066, signed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, which gave the military the power to ban any citizen from a 50- to 60-mile zone along the West Coast and into Arizona, and to transport citizens first to temporary assembly centers and then to the 10 “relocation centers” established in rural Arkansas, Arizona, California, Colorado, Idaho, Utah, and Wyoming.

The executive order was primarily applied to Japanese immigrants and Japanese Americans in the western states, relocating—in baldly euphemistic language—119,000 people. Sixty-two percent of the relocated were citizens, a third of them were children, and they were forced to move with as little as 48 hours to sell or store any possessions they could not carry. As Yamasaki told TIME, "Our people had to sell everything for 10¢ to 15¢ on the dollar. The people who bought their businesses and houses knew they had them over a barrel."

He was far from alone. Once you start to look at postwar American design through the lens of Japanese American history, you realize that the two are inextricable. Japanese American designers gave the country its Twin Towers and its first modern airport, as well as the magazine covers that featured the latest in architecture. They gave America its Corvette Stingray and its spaghetti-eating sequence in Lady and the Tramp and the look of jazz. They made the ads that sold Eames chairs and designed furniture themselves, of bentwood and butterfly fasteners and burl. They wove the California craft movement, populated cities with public art and pocket parks, and developed suburbs with sculptural landscapes.

If you are reading this site, you know at least some of these names: Minoru Yamasaki, Gyo Obata, Ray Komai, Larry Shinoda, Willie Ito, S. Neil Fujita, Tomoko Miho, George Nakashima, Kay Sekimachi, Ruth Asawa, Hideo Sasaki, Isamu Noguchi.

Most spent part of their teens and twenties in one of 10 War Relocation Centers, a fact I had failed to find, or failed to focus on, in many previous trips through design history. Modernist history credits the German emigrés for bringing Bauhaus ideas to Black Mountain, Cambridge, Chicago, and Los Angeles. It also credits Japanese design filtered through Western eyes like those of Bruno Taut and Frank Lloyd Wright, or translated for an American audience by House Beautiful’s influential editor Elizabeth Gordon. In 1960, the Japanese term shibui became the magazine’s “buzzword,” defined as, among other things, “craftsmanship, intelligence of design, understanding of materials, imagination.”

But the Japanese American contribution is different. A number of these designers were educated in the Bauhaus tradition at American schools, or via trips to Europe. Some grew up speaking Japanese, practicing calligraphy and kendo, while others were first exposed to origami, painting, or weaving in the camps, where skilled artists and artisans made work to document and mentally survive incarceration.

To commemorate the 75th anniversary of Roosevelt’s executive order, several museums have organized exhibitions around the topic. The Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles opened Instructions to All Persons: Reflections on Executive Order 9066 on February 18, 2017. It has previously curated exhibitions on the art, craft, photography, and landscape created in the camps and by internees after the war.

The Crocker Art Museum in Sacramento will show Two Views, with photography of the camps by Ansel Adams and Leonard Frank. And the Noguchi Museum in New York has just opened an exhibit focusing on artist Isamu Noguchi’s unique self-internment at Poston in 1942, including works made before, during, and after his seven months in Arizona, as well as architectural drawings he made for the improvement of the camp. (Several of the camps are now national parks and historic sites; Carolina Miranda visited Tule Lake and Manzanar last fall for a story in the Los Angeles Times on civil rights sites in California.)

Recognizing the Japanese American detention camp experience seems especially important at this moment: Last fall, when then-candidate Donald Trump floated the idea of a Muslim registry, many were quick to draw a line between that suggestion and the fact that the U.S. has racially profiled and imprisoned its own citizens before. Last week's executive order, halting immigration from seven foreign countries and arresting movements to and from the United States based on country of birth, makes "aliens" and potential terrorists out of thousands of refugees and immigrants—as did Executive Order 9066.

*This article was originally published by Curbed.com on January 31, 2017.

Curbed © 2017 Vox Media, Inc.