In 1956, at the age of 56, Seitoku Shimabukuro, overwhelmed by debt, decided to migrate to the Peruvian Amazon to save himself from shipwreck. The once successful businessman, owner of a school, one of the most influential people in the Japanese colony in Callao (Lima), goes into the jungle for five years. Alone, far from his wife and six children, he leads a life rich in adventures that is captured in the book Memories of the Amazon.

Its author is the youngest of his children, Luis Takanobu, who took as his main input the book Amazon Sanka (Discovering the Amazon) , written by his father. Translated into English and Spanish, Luis thought that the work was arid, that it did not match the skillful and histrionic narrator that was his father, the man who moved those around him with stories like that of the 47 ronin. “I cried when your dad told (stories),” a woman once told him.

Luis believes that his father sinned from modesty, or perhaps modesty. Or both. Thus, he decided to rewrite his father's story, enriching it with the colorful stories he heard from Seitoku himself. There was a gap between the writer dad, flat and dry, and the narrator dad in the one-on-one, exuberant and entertaining, that he set out to bridge.

He had been pursuing the idea for a long time, but for one reason or another he could not put it into practice, until, like an answered prayer, came the contest organized by the Editorial Fund of the Peruvian-Japanese Association for its series “Memories of the Japanese immigration. He participated and won.

IN SEARCH OF INTERNAL PEACE

Seitoku Shimabukuro was dedicated to food trading, cattle raising, and rice cultivation in the Amazon. However, the Issei did not migrate to the jungle only for economic reasons. Behind it there was, perhaps, a more powerful reason: the need to reconstitute oneself, to recover strength, to find inner peace, to start from scratch in a place where no one knew him, where there was no social environment that pointed him out.

“The important thing about having been in the Amazon is not so much about having earned okane (money), because it really wasn't a big deal. The most important thing is that the old wine totally changed: he was five years older, but with incredible vigor, rejuvenated. The emotional, spiritual issue was extraordinary. He was a competitive guy, I would even say aggressive. He fully recovered. He recovered to the point of being Mr. Shimabukuro from before. It wasn't a big deal to go to the jungle, but emotionally it was a big push,” says Luis.

One of the most intense experiences his father had was an ayahuasca session that the book narrates in detail. Stricken by the departure of Arichan, the son of a Japanese friend to whom he taught arithmetic and read, and who drowned in a river while on his way to his classes with “don Shima”—as the little boy called him—Seitoku was able to reunite with the child thanks to his journey with the plant. Arichan was at peace, he was no longer suffering.

The ayahuasca session later took him to his village in Okinawa, where he saw himself at twelve years old and his mother telling him that his father, who died the day before, wanted his children to study as much as possible, because as he used to say “gakumon wa buki da” (“education is a weapon”).

This phrase fueled his life, pushing him to create in 1942, in secret, when the teaching of the Japanese language was banned due to the war, the Minato Gakuen school for the children of the Japanese in Callao. Almost 20 years later, despite the fact that the construction of the land for Minato Gakuen and its equipment caused the debts that almost ruined him in Callao, he was the architect of the construction of a school in the Amazon: the Arichan School.

“MY MOM HAD EXTRAORDINARY PATIENCE”

In parallel to the story of Seitoku in the Amazon, another was developing in Callao. “When my dad went to the jungle, the one who stood up for all of us was my brother Frank, he stayed in charge of the whole family,” remembers Luis. Frank is the second of the brothers; The oldest was in the United States at that time.

Luis was ten years old when his father went into the jungle. “He just left. “Where did Otosan (dad) go?” he asked. He even thought that his father had died.

“My mother was crying alone and I didn't understand what was happening. My mother was a quite beautiful woman, she was 44 years old, she was young. Being left alone required a lot of loyalty to the husband who was in the jungle. For my mother it was very painful, the economic situation at home was terrible. We had a cafeteria of this size (in reference to the small room where the interview takes place), with five tables,” he remembers. “My mother had extraordinary patience,” he adds.

“I criticized my father because my mother suffered a lot, I have seen her cry many times in solitude, and it made me angry that the old man was not here to defend my mother, suffering with arthritic hands, getting up at 6 in the morning to go to work at a miserable business. “It made me angry and I maintained that anger for many years.”

He saw his father again about three years later, when he returned to Lima to arrange his admission to the Guadalupe school. Once the procedures were completed, while he was preparing to travel to the jungle again, Luis asked him: “Where are you going?” “I have to work there in the mountains,” his father responded.

More than 60 years after his father's migration to the Amazon, he still has a hard time finding the words to define what he did: “It is a mixture of courage, I don't know if it is cowardice, fear, dignity, pride, no. I know how to identify it exactly.”

THE ENTREPRENEUR WHO LOOKS FOR OPPORTUNITIES

Luis Shimabukuro maintains his serenity, he holds his gaze, his voice remains firm, it does not crack despite the harshness of what he narrates. He seems like a man at peace, reconciled with his family history.

Writing Memoirs of the Amazon has been important in that healing process. He has poured his own experience into the work. After four years without work in Lima, where all doors were closed to him, he moved to the Amazon, where he lived between 2009 and 2012. The Seitoku Shimabukuro who appears in the book is also him. Their liberation is also yours. “I'm sure I wouldn't have written it the way it is written if I hadn't lived there for four years,” he says.

No one has had to tell Luis the fear and helplessness that one feels when one is lost in the immensity of the jungle, alone, at night, nor the need to implore divine help: “My God, help me, don't leave me here, "I don't want to die here."

The difficult Amazonian stage of his life helped him better understand his father, whom he defines as “the typical entrepreneur who looks for opportunities.” He inspires him. “I try to have the fighting spirit that my father had.”

That fighting spirit that made its rebirth possible. Seitoku Shimabukuro, fully recovered, left the Amazon in 1961 to move to the city of Huánuco, this time with his wife and some of his children, among them Luis. In Huánuco they ran a bakery, a successful business that allowed Seitoku to pay all his debts.

“Many creditors didn't know if he was alive or dead, when he started paying the debts they said 'ah, he's alive' (laughs),” Luis remembers. He even went to pay some on behalf of his father, who returned sums of money above what he had been lent, recognizing the interest. When the creditors told him “this is too much, you are wrong,” Luis replied “my dad is in charge, you just get it.”

In 1972, debt-free and “with a clean face”—as Luis says—Seitoku Shimabukuro returned to the capital. He was a new man.

The author of Memories of the Amazon hopes that his readers find in the work “a look back with a vision of the future.” “The idea of the book is 'don't leave Peru, stay in Peru, even if you're old you have opportunities,'” he says.

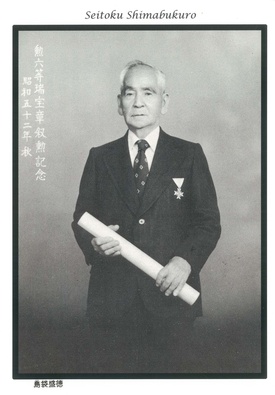

His dad is there to prove it. At 56 he started from the bottom, rising from the rubble, and at 61 he reinvented himself as a prosperous merchant. At the age of 74 he published his first book and at the age of 77 he was decorated by the government of Japan for his contribution to education and friendship between Peru and Japan.

* This article is published thanks to the agreement between the Peruvian Japanese Association (APJ) and the Discover Nikkei Project. Article originally published in Kaikan magazine No. 109, and adapted for Discover Nikkei.

© 2017 Texto y fotos: Asociación Peruano Japonesa