How did they (Hiratzka family) come back to California?

Well, I was in Texas and Jordan went to Ogden. I went to Crystal City and joined my family. We were separated for two and a half years and in the meantime Jordan was in Japan with the MIS. Went to the Philippines and they closed up those bars. They stayed there very shortly in Manila then they were sent to Japan. The war ended when he was on the ship going to the Philippines in 1945.

That’s when my dad got orders saying that people in Crystal City had a choice: Do you want to go back to where you came from or do you want to go to Japan? The Peruvians weren’t able to go back at that time. A lot of people went to the LA area. But my dad said no, we have nothing to go back to in Santa Maria. We rented a house, we don’t own property, and we says my mother is all alone in Japan running the farm, so I’ve got to go back to Japan. My mother was not very happy about going back to Japan but she and my two brothers went with my dad.

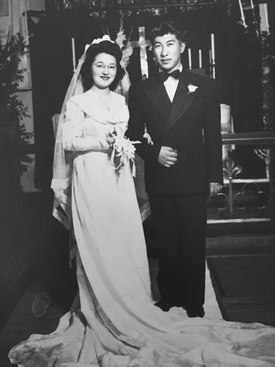

But before that in Crystal City, when the decision was made, what about Maru? In the meantime Jordan was in Japan, and we’d been corresponding all the time and he said he would receive my letters that said ‘Prisoner of War’ on the stationary and they’d be cut up, censored. But we kept up and he wrote his dad and said ‘Maru said she’s going back to Japan with her dad. I don’t want her to go back.’ So his dad wrote my dad and said I think Jordan wants to marry Maru so, when you get your orders to go to Japan please send Maru to us in Ogden and then she can wait for Jordan to come back. So that’s what we did in December, it was very cold. I had to say goodbye to my family. They picked me up in the car at our place and I said goodbye to my brothers, my mother, and aunt. My aunt was like a second mother. I had to say goodbye to them and Papa went with me to the gate, and there we said goodbye. Then they put me on a bus to San Antonio, all by myself. I had just turned 19.I was afraid, I was protected. I was very naive, I had never been out on my own, never. But there was another girl who left camp, too. And Mama had packed a little snack for us so we found a park near the San Antonio river walk park. Then at the train station, do we use the Black or white bathroom? That was the first time for us to have that. So I went to the white side. What if I get chased out? But nobody bothered us.

Wow.

So once we got on the train I happened to sit next to a young lady from Texas and we were talking about everything. And there were a lot of GIs on the train, and they were bothersome. Good thing she was there, she would tell them off.

They were bothering you two?

They were bothering all the women, GIs. Then I said I was very sympathetic about the Black people and she says, ‘Well, you won’t have me rubbing elbows with an ‘n.’ That’s what she said. So I said oh, okay. But she was good to me and fine. So it took me three days to get to Ogden.

And you had wanted to marry Jordan, of course.

Yeah, since high school we knew each other, we did a lot of things. We liked each other. It’s comforting when you have a friend that you’ve done things with and you like things with. And have things in common.

Were you conflicted or upset about your family? Did you feel like you should go with them?

No, my dad said ‘No, you go with Jordan.’ You’ve known him for all these years. And they knew the parents. But I missed out on my college because I wanted to be with my parents as long as possible. So I said no [to college], so for at least for two years I was with my parents.

So they knew for a while that they were going back to Japan. Where in Japan?

Okayama. Next to Hiroshima.

What happened when the bomb was dropped, and how did he know his mother was okay?

They didn’t. But somehow he said that she’s still running the farm by herself, without really knowing what her condition was.

What happened once they were there? How did you find out about them?

After they sent me to Ogden a week before they were to go, they were on a train to Seattle to get on a ship to go to Japan. They landed in a place called Uraga near Tokyo Bay. And my brother said that the women got off the ship regularly but the men, they had to climb a rope ladder to get off the ship.

I wonder why.

I don’t know why. My brother didn’t explain it to me because he was young, too.

What happened after they arrived?

Papa said when they got there, Grandma thought she was seeing ghosts. She did not receive the telegram [that the family was arriving]. So here are my father and two brothers and mother, coming all at once.

Was she happy or more just surprised?

I think she was more shocked. I didn’t hear the detail of her reaction. She’s very typical Japanese mother-in-law that made it hard for my mother. My mother said she was trying to help her. Being on a farm, at least you can grow vegetables and have something to eat. City people were having a hard time. But my mother said they were peeling satoimo, that slimy potato. That’s hard to peel because it gets very slimy. My mother was peeling those and Grandma would come over and say you’re taking too much! Anyway, Japanese mother-in-laws are hard on their young daughter-in-laws. That’s a known thing I think. It was hard for her. When the time came later that she could correspond, she says I’m so glad you didn’t come with us.

How long were they in Japan?

They just stayed, until they died.

Wow. Did you ever go visit?

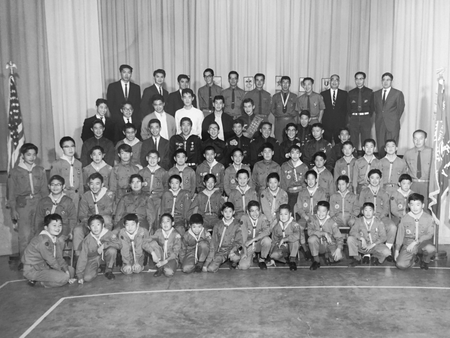

I went a number of times. but the first time I went was 22 years later because you know I got married, I had children and Jordan went to school. So about the time we could go it was because of Jordan’s Boy Scout troop. He started a troop exchange with a Japanese group near Osaka. I got on the plane with them, took my two children and flew to Japan. While he did his Scouting I went to visit my parents with my children.

How was that visit for you?

I almost didn’t recognize my mother. I saw this lady that I thought was my mother and I went to hug her, and it was my mother’s sister.

Do you feel a loss for what happened during the war?

No, not really. [If this didn’t happen] we would’ve been in the same little community but now we’re spread out. We’ve grown. So it’s been good, too, in some way that this happened. Of course nobody likes war. But still some good has to come out of something.

And what about your parents? Do you feel their lives were interrupted by this?

Well, I don’t know. But the Japanese are very strong. You know the yamato-damashii? “Japan is strong.” We can’t be wrong, and all this.

Yes, save face. Pride is everything.

Pride, yes. I know even in camp when it was declared Japan lost the war, some of these men were very adamant about Japan, they just couldn’t believe it. They went back to Japan thinking that they did not lose the war.

But the Japanese, they’re just so strong. And creative, I just admire the way they do things. They just improve things, they don’t stop. They just amaze me what they can do.

*This article was originally published on Tessaku on March 24, 2017.

© 2017 Emiko Tsuchida