Textile artist Kay Sekimachi and her mother and sister were taken by bus to Tanforan Assembly Center. In an oral history at the Archives of American Art, she recalls,

And then, we were assigned rooms in a barrack, and there were cots and we had straw mattresses, and it was just bare other than the cot. And somehow, we managed for—I think it was about three months that we were in Tanforan. But I must say, the first few days, I thought, when we had to stand in line at the mess hall for meals, and I really thought, gosh, are we going to survive, because nothing was organized …

Well, the older Niseis, who were, like, in Cal by that time, they started a school. And then Professor Obata from Cal was in our camp, and he started an art school. And so, that's where my younger sister and I went to. So every day we drew and painted.

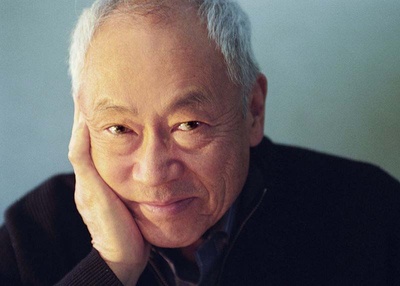

Chiura Obata set up art schools first at Tanforan, and later at Topaz, in Utah, while simultaneously documenting life in the camps through his own paintings. One of Obata’s four children, Gyo Obata, was spared incarceration by transferring from Berkeley, where he was enrolled, to Washington University in St. Louis, the only architecture school willing to accept Japanese American students. He ended up as part of a class of 30 Japanese American students who enrolled in the fall of 1942. As several alumni recalled in a 2009 article in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, this placed them in a bizarre position.

[Richard] Henmi, who visited his parents at a camp in Jerome, Ark., recalled the surreal situation of having to pay for meals there as a “visitor” while his family received them for free. Obata, who also stayed with his family in the camps, recalls a similar experience.

“It was just crazy,” he said. “I was a free person, and they were like prisoners.”

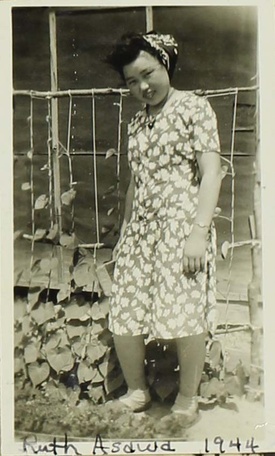

Sculptor Ruth Asawa, who was 16 in 1942, had grown up attending a Saturday school for Japanese language and culture. In the weeks after Pearl Harbor, her father Umakichi Asawa “dug a big hole to bury the Kendo gear, and burned the hakama, beautiful Japanese books on flower arrangement and tea ceremony, Japanese dolls, and Japanese badminton paddles.” In February 1942, FBI agents arrested Umakichi, searching the house for suspicious material. While Asawa, her mother, and six siblings were taken first to a temporary holding center at the Santa Anita racetrack, and then to the camp in Rohwer, Arkansas, her father was held separately. The family was not reunited for six years.

Curator Karin Higa writes in an essay on Asawa’s work,

Thus, in a pattern that would repeat in other instances during World War II, the negative consequences of her Japanese ancestry turned into an unprecedented opportunity. A section of the racetrack grandstand, adjacent to a section where internees were used to weave camouflage nets for the war effort, became a de facto art studio. Painter Benji Okubo had been the director of the Arts Students League of Los Angeles, a position once occupied by his teacher Stanton Macdonald-Wright. In Santa Anita, he and painter Hideo Date, a League associate whom he had first met at Otis Art Institute, carried on the activities of the Arts Students League in the grandstand. They were joined by Tom Okamoto and Chris Ishii, who had attended Chouinard Art Institute.

Okamoto, Ishii, and James Tanaka were all employed as animators by Disney Studios. Growing up, Asawa had always copied cartoons, and now she had access to some of the most influential practitioners in the field. “How lucky could a sixteen-year-old be,” Asawa has said. She also did her first weaving in camp, volunteering to make Army camouflage nets (a process documented by photographer Dorothea Lange at Manzanar), though her breakthrough would come later, after viewing Mexican fishermen weaving wire, a technique she would transform into hanging, weightless, anemone-like sculpture.

Asawa used education as a means out of the camp. The American Friends Service Committee worked from the earliest days of the executive order to get people out, first by finding colleges and universities in the East and Midwest who would accept Japanese American students, and then by setting up hostels for internees seeking jobs in the same cities. Asawa attended Milwaukee State Teachers College on a scholarship. In her fourth year, which would have consisted of student teaching, she was told that no school in the state would hire her. She dropped out, enrolling instead at Black Mountain College, which set her on the path to becoming an artist.

“I hold no hostilities for what happened; I blame no one,” Asawa told an interviewer in 1994. “Sometimes good comes through adversity. I would not be who I am today had it not been for the internment, and I like who I am.” Asawa pulled no punches when asked to design the Japanese American Internment Memorial in San Jose in 1994. The memorial, which, like much of her later work, is public art and figurative, depicts the camps in a large, bronze bas-relief, complete with guard towers and guns. Vignettes show FBI agents forcing a Japanese American man to leave, which is what happened to Asawa’s father, as well as scenes of camp life, like two families sharing a room, separated by only a curtain.

Marilyn Chase, who is writing a biography of Asawa, considers it an important visual reminder of what she and others suffered. She told me:

When it was completed, the memorial resonated with crowds, shown in photographs of the dedication day in March 1994, standing up to twelve deep to view and touch the bronze reliefs. Like her other representational pieces, it enjoyed great popular success.

In my research, I'm interested in how Asawa's public statements about camp life and experience expanded and evolved over the decades, from quiet stoicism to a more explicit discussion of the privation she and others endured. Yet she rejected the mantle of victimhood, letting her hands speak most eloquently for her in the bronze panels.

The other way out of camp was the military. In February 1943, the Army created the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, an all-Nisei (first generation Japanese American), segregated unit. Ten thousand Japanese Americans from Hawaii, who had not been interned, volunteered, along with 1,200 from the camps. Among them was S. Neil Fujita, in camp at the Heart Mountain Relocation Center in Wyoming. Before the war, he had started his artistic training at Chouinard Art Institute in Los Angeles, to which he would return, funded by the G.I. Bill, in 1947. But first he became a soldier, fighting in Italy and France as part of the most highly decorated unit in World War II. After combat ended in Europe, he was sent to the Pacific to serve as a translator.

After graduating from Chouinard, where he took a few graphic design classes in his final year, Fujita moved to Philadelphia, first receiving notice for an award-winning ad for the Container Corporation of America. Columbia Records hired him away, and he created his best-known work in the 1950s, designing abstract, brightly colored record covers for Dave Brubeck and Charles Mingus, among others. Later he moved on to books, creating bold, memorable typographic covers for Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood and the puppeteer’s “G” for Mario Puzo’s The Godfather. In his 2010 obituary in the Guardian, Milton Glaser is quoted saying Fujita “distinguished himself by having a rigorous design objective. It was a kind of synthesis of Bauhaus principles and Japanese sensibility.”

* * * * *

The names in this piece are the successes, and many of them, on the cusp of adulthood in 1942, learned skills that changed the course of their lives. Others, older, with interrupted careers, or dependents, or no access to an arts career, simply had to work to live. “What’s most heartbreaking to me is that they never went back to it,” says Delphine Hirasuna, curator of the 2010 Smithsonian exhibition, “The Art of Gaman: Arts and Crafts from the Japanese American Internment Camps, 1942-1946.” She took her exhibition’s title from the Buddhist term Gaman, which means “enduring the seemingly unbearable with patience and dignity.”

“They had to feed themselves and their family. People left the camps, they didn’t know where they were going to live, they didn’t know how they were going to live, and these things”—the camp-made objects in her exhibition—“got left behind.” The need to excel that Miho described, and these designers embody, doesn’t excuse the racism and terror of Executive Order 9066, but may explain its oblique, one-line presence in the histories of postwar architecture, design, and craft.

In 1988, President Ronald Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act, offering a national apology and $20,000 in compensation to each camp survivor.

Gyo Obata, whose father’s art classes meant so much to those interned at Tanforan and Topaz, designed the building for the Japanese American National Museum dedicated the same year.

Sasaki and Yamada were on the landscape committee for the creation of the Manzanar National Historic Site in 1992, the 50th anniversary of Executive Order 9066.

Architect Alan Oshima, who had been interned at Tule Lake, designed the basalt and concrete California State Historic Site marker for the camp that was placed along State Highway 139 in 1979.

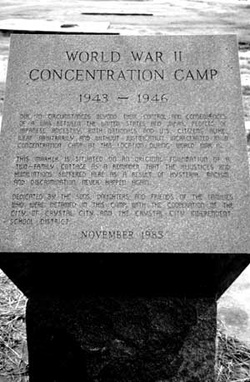

Architect Alan Taniguchi designed a monument placed at the now-vanished camp in Crystal City, Texas, where his family was incarcerated.

It’s fitting that these Japanese Americans should be able, like Asawa was with her San Jose memorial, to use the design abilities that allowed them to survive with dignity to make this history more present for all Americans.

*This article was originally published by Curbed.com on January 31, 2017.

Curbed © 2017 Vox Media, Inc.