Growing up at the Empire Hotel in downtown Yakima, Fukiko Takano enjoyed hunting for coins in the lobby’s deep leather couches and watching people come and go from three movie theaters across the street.

And when parades passed the hotel at 121/2 E. Yakima Ave., she could head out onto the sidewalk for a closer look at the floats, the bands and the animals, or she could watch from her family’s second-story rooms of the building on the south side of the street.

Her parents, Bunji and Seki Takano, owned the Empire in the what was then known as city’s Japan Town district. The hotel comprised the upper floors of the stone building, which was demolished decades ago. A Wells Fargo bank drive-through and parking lot cover the site today.

The Takanos and their four children lived in three large rooms on the second floor — one for sleeping, a kitchen/dining room and a living room also used for school studies and music lessons.

“I played the violin and one sister played the piano. We had a piano,” said Fukiko Takano, who is 92 and lives in Des Plaines, Ill.

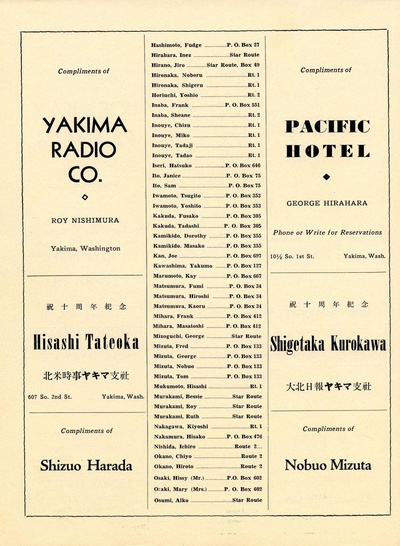

People began calling it Japan Town in the 1920s, when residents of Japanese ancestry operated and owned a variety of businesses filling the block bordered by Yakima Avenue, South First Street, Chestnut Avenue, and South Front Street. That continued until June 1942, when 1,017 Yakima County residents of Japanese descent were forced to leave their homes for the Heart Mountain Relocation Center in Wyoming.

Only about 10 percent returned. Like the Takanos, many who ran businesses and owned buildings in Wapato, Toppenish, and Yakima had to sell them for the best price they could get after President Franklin Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066. Decades passed and structures decayed.

Fukiko Takano finished high school at Heart Mountain and headed to North Carolina for college, getting a job as an accountant for Church World Service, now CWS. She worked in New York City before moving near Chicago, where her parents lived.

Though her father and three sisters never returned to Yakima, Takano made the trip with her mother and her older brother, Tadao.

She remembered the years of walking to Madison Elementary School, to Washington Junior High, and Yakima High, of performing in pageants at First Congregational Church, though her parents weren’t Christian. She recalled attending concerts and dances, even a Highland Fling. Her mother made her plaid pleated skirt.

Despite the difficulties of imprisonment, Takano spoke of her hometown with fondness.

“All of us went to Yakima High School, and incidentally when we left for evacuation, the teachers wrote to us,” she said. “And not only that, they sent us fruit when the holidays came. ... They would send us crates we would share with people in the camp.”

“It was very hospitable to us. There was no hostility in that town that I can remember,” Takano said. “I have only good memories, really. That includes the people.

‘We had big porches’

Parking lots cover most of what was Japan Town, making it difficult to imagine daily life in March 1927, when Yakima had 43 businesses owned and operated by Japanese immigrants and their families. Nearly all faced the streets that defined the district.

That year, the city had nearly 26,000 residents, including about 150 of Japanese ancestry, according to the 1928 edition of the North America Year Book, which details Japanese communities in several Washington cities.

There were included 15 hotels, six Western-style restaurants, six agricultural trading companies, three laundry and bathing shops, three cigarette and variety stores and several other businesses.

The Empire’s main entrance stood between two businesses. “It was a very busy street,” Takano said.

Hotels of the time occupied upper floors, with storefronts on the ground floor. They operated more like today’s apartments, with tenants living for months or years in a single small room with a sink. Common areas included bathrooms, and some hotels offered laundry facilities.

Renters chose bigger rooms when they could afford them. At the Empire, an Army recruiter lived in one of the larger rooms. An Italian cook lived in another and an African-American couple occupied another large room, Takano said. Many of the Empire’s tenants worked for the railroad, she added.

Everyone in Japan Town knew each other, socializing informally amid the open spaces behind the buildings.

“We visited each other on the back porches. We had big porches,” Takano said. “There were so many hotels along there and they were all Japanese.”

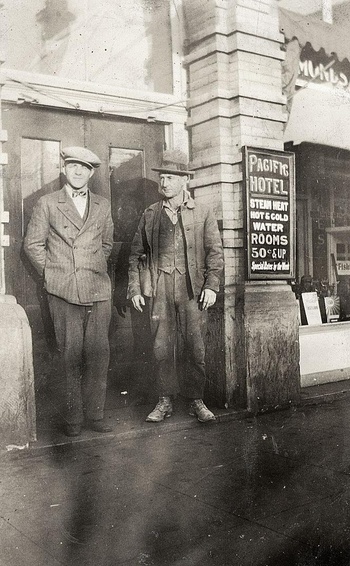

The Takano family, which also included daughters Fumiko and Tomiko, were particularly close to George and Koto Hirahara, who ran the Pacific Hotel at 101/2 S. First St. Their only child, Frank, ran on the Yakima High track team with Tad Takano.

The Hiraharas began working at the 60-room hotel in 1925, moving to Yakima from Toppenish. They began running the hotel in 1926. Koto, who was one of the last “picture brides” to come to America in 1924, listed her “position and duties” as “managing, office clerk, chambermaid, cleaning, bookkeeping and laundering work,” according to government documents.

They bought the hotel in 1926 and lived in rooms on the northeast corner of the second floor.

The Hiraharas were one of the first families to return to Yakima, and George became an American citizen in 1954. He and his wife are buried at Tahoma Cemetery.

Their hotel, which now houses Yakima Maker Space Gallery and the Downtown Association of Yakima, is one of three former Japan Town buildings on South First Street. Owner Joe Mann, an avid preservationist who has several historic buildings, plans to convert the upper two stories into apartments, including a two-story condo for he and wife Kathy. No one has lived there since the mid-1970s, he said.

“We’re still kind of deciding what we want to do with it,” Mann said.

‘An amazing person’

On South Front Street — the Japan Town district’s western edge — Sam Migita owned the Sunrise Cafe and ran the California Hotel.

An empty lot covers the site of the cafe at 23 S. Front St., but the hotel building still stands at 15 S. Front St. It’s one of two buildings that comprise The Olde Lighthouse Shoppe, a thrift store operated by the Yakima Union Gospel Mission.

Only one other Japan Town building remains on that block of South Front Street, and none are left on Yakima and Chestnut avenues.

Migita was 21 when he immigrated to the United States, paying his fare for the ship from Alaska to Washington state by working as a cabin boy, according to a newspaper article.

By the 1930 census, he was living with wife Tora and teenage daughter Hisako, said his great-grandson, Dr. David Perley of Los Angeles.

Hisako died in 1930 of tuberculosis, which she caught from a hotel boarder. Tora died in 1938. Both are buried at Tahoma Cemetery. Migita married Perley’s great-grandmother in December 1941.

“He was a truck farmer and he operated the California Hotel and he owned the Sunrise Cafe. He was ... doing one of those things or all three of them at the same time,” said Perley, who began researching his family history a few years ago.

“He worked in a lot of cafes; I think more than one. He was just real busy, depending on what year you look at.”

Before being forced to leave Yakima in early June 1942, Migita sold the Sunrise Cafe for $300.

“Other cafes had only their equipment sold, which would mean (owners) essentially got nothing,” Perley said. “It looked like a whole bunch of cafes were getting low prices. A whole bunch of them were being sold for equipment only. One sold for $200.

“I think (getting) $300, he did OK compared to the other people,” Perley said.

A leader in the Yakima Buddhist Church, Migita in 1945 arranged for religious items to be shipped from Heart Mountain to the church in Wapato. That shipment may have included the Amida Buddha enshrined in the altar today.

Good-natured and soft-spoken, Migita and his wife moved to St. Louis after leaving Heart Mountain. He worked as a landscaper and enjoyed playing poker, smoking cigars and watching baseball and boxing.

“I didn’t get to know him too well because I was in Los Angeles and they lived in St. Louis. They moved there after (World War II),” Perley said. “I just remember being amazed at how strong he was for being over 90 years old.”

Migita died in St. Louis in 1980. He was 102.

“He was a pretty amazing person ... involved in the community quite a bit and very active throughout his whole life,” Perley said.

*This article was originally published on Yakima Herald-Republic on April 11, 2017.

© 2017 Tammy Ayer