This is what Regina Boone knows about her grandfather: His name was Tsujiro Miyazaki. He came to this country, family legend has it, as a stowaway on a ship from Europe. By 1941, an ocean and more away from his native Japan, it seemed like Miyazaki had found a home. In Suffolk, VA, of all the unlikely places, in the heart of a black community in a rural town in the segregated South. Miyazaki owned a restaurant, the Horseshoe Café, and he’d built a family with Leathia Boone and their two sons. A prosperous businessman, he donated to local charities and had friends in the community. They called him Mike.

Until Pearl Harbor.

In the early hours of December 7, 1941, the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service launched a surprise attack on the U.S. military base at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii. The devastating attack killed 2,403 Americans, pitching the U.S. into World War II. And a wave of suspicion about Japanese Americans consumed the nation. Before the day was over, Miyazaki was in U.S. custody, first at Ft. Howard in Maryland, then at the Rohwer Japanese American Relocation Center in Arkansas.

He never returned to Virginia. By 1946, he was dead.

The American government would ultimately intern as many as 120,000 Japanese Americans under executive orders issued by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1942 and upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1944, a policy based on open prejudice and the mistaken belief that Japanese Americans were a “fifth column,” an enemy force inside American borders.

What happened to Miyazaki is a mystery Boone has only begun to unravel. A longtime Free Press photographer, Boone took a voluntary layoff offered to employees of the newspaper late last year. She’s going back to Virginia, where she plans to research her grandfather’s history.

And at a time when racial tensions are high, when immigrants are viewed with skepticism by those in power, Boone wants to tell her family’s story, and sat down with Free Press columnist Nancy Kaffer for this article. She wants to show the toll—exacted on Americans and American families—of a policy once deemed to be in Americans’ best interest.

“I want to put this story together,” she says. “I want to share it. I want others to learn from it. I want us not to repeat it.”

How life was, at first

As a kid, people used to ask me, “What’s your dad?” I would say, “He’s black,” because that’s the only answer I knew. … One day, I asked him. He was, like, yeah, your grandfather was Japanese but the American government…

He’d begin to tell me the whole story of what he knew. But my dad only knew a limited amount of the story, because he was only a kid when this all happened. And his father never came back.

My dad (Raymond Boone) was born in 1938; 1941 is when they came and got my grandfather after Pearl Harbor. He was interned, and he never returned. He knew that his father owned a restaurant called the Horseshoe Café. He knew that my grandfather was in the black community, that the white community had not accepted him and that the black community had welcomed him.

His restaurant was the place everybody went in that community. I think he was dealing in fusion before fusion was hip. There was a dish called “yok” that everybody used to get. I think he just used what he had, ketchup and soy, noodles and vegetables, and it’s this medley of stuff that’s been stir-fried together. I’ve never had it, but my dad talked about this food because it became kind of a regional food in this little area. If you ask people down there from the black community, even the white community—if you ask what “yok” is, they will say, “It’s this Chinese food.” I think it goes back to his restaurant.

Then there’s that other little sliver of our American history, that interracial marriages were against the law until (the U.S. Supreme Court overturned anti-miscegenation laws in) 1967, with Loving v. Virginia. My grandmother and grandfather were unable to be married. That’s why my name is Boone, not Miyazaki. …

In a supportive brief filed in Loving v. Virginia, the Japanese American Citizens League noted miscegenation laws that barred marriage between blacks and whites were oblique on the subject of Asian-Americans’ racial classification, and that such determinations were generally made on an impromptu basis by local officials.

I think they were just together, but I think it was just…he was accepted. He was Japanese, but he was one of them. He was part of the community. He owned the restaurant, he just happened to be Japanese.

Nobody was judging him, I don’t think, until the war came.

Why nobody talked

In my early teens, I started asking a lot of questions—“Dad, so what’s the deal, who’s your dad? Where did he come from? Tell me more”—and I think it made him very uncomfortable, and I sensed that, so I stopped asking. My grandmother was still around, but he told me not to ask any questions, and not to ask anyone else. Basically, he put a lid on it for many years.

I became more and more curious as I got older, realizing more about the history of internment camps—I hate that word, “camps”; they were basically prisons; you couldn’t come and go—with World War II. When the government paid reparations to people who had been interned, I remember asking my dad about that: Was he going to get that money? He said no. “I’m not going to be paid off by tokenism from the American government.”

And once again, we didn’t talk about it.

When I was in college, I decided I wanted to go to Japan and live there. … I taught in English in nine different schools and lived in the countryside of Osaka. I was going to make that my mission to go there and find members of my family. Then I found out where my grandfather was from—Nagasaki, and Nagasaki was bombed. So I realized I had no family, most likely.

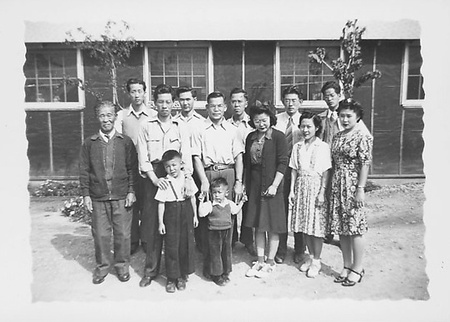

From Japan, Boone started researching her grandfather’s life, with the help of the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles, which directed her to the Library of Congress. Eventually, a thick manila envelope arrived, the total government record of her grandfather’s internment.

They sent me this huge package to Japan. It had all the letters my grandfather had written from the internment camp to my grandmother in Suffolk. There were beautiful letters to my grandmother, asking about my father and my uncle, telling my grandmother about life in the internment camp—his daily work regimen, how much he got for a stipend, life in the internment camp.

Also within that package, you could see where the government had come in and seized his restaurant. They itemized everything, from salt and pepper, to toothpicks, to how many bags of flour he had, to even details of who he donated money to in the community, who he had a subscription with—he had a subscription with Reader’s Digest.

Supposedly, some relative was left in charge of my grandfather’s stuff, but those people are all dead, so I can’t even ask questions. Like, what happened to the car? What happened to the bank account? I know the bank account was seized, all of those things were seized and shut down.

I think this was one of those things—nobody talked about it.

Documents in the Library of Congress file show Miyazaki attempted to navigate the return of his assets. A bank account in his name held $867 the month he was taken into custody—$14,257 in today’s money—and his restaurant was stocked with equipment and food. The federal government rejected a representative Miyazaki designated to take receipt of his property (Boone suspects it is because her grandfather’s friend was black), and the record does not show what became of his assets.

In 1945, Miyazaki applied for indefinite leave from Rohwer, government documents show. A letter from a hotel manager in Chicago showing proof of future employment was a crucial component of the application. Documentation seems to indicate Miyazaki’s leave was approved. Social Security Administration documentation shows that Miyazaki died in 1946.

I think there was shame involved. I think there was shame because they weren’t able to be legally married. There was shame because he was Japanese, and it wasn’t a traditional relationship. He wasn’t from the same background. Shame because he was from the enemy of America. I can’t even imagine my dad’s psyche, and my grandmother, too … This Southern, very small town, during World War II, Japanese and black people … shame, embarrassment, deep sadness … I think it was every emotion. Even looking at my father, he’s a direct mix of black and Japanese. So maybe he felt … I never knew.

What we all lost

It affected him, and it affects me in many ways. There are so many questions. … My dad never knew his dad. This whole part of him, this whole chunk of him was denied to him because the American government declared Japanese Americans enemies.

My father and my uncle grew up very poor in Suffolk. But my dad was really smart, so teachers took him under their wings. The black dentist who came from Boston to become the dentist in town took an interest in my father.

Raymond Boone became a celebrated journalist, first as a White House correspondent, then as editor of the Baltimore-based Afro American Newspaper and later as founder of The Richmond Free Press, a weekly African-American newspaper.

My dad was pretty independent. … He had a loving family, but I think this whole situation just caused a major schism, caused a lot of dysfunction to happen. … Your father is the so-called enemy, and you’re black in the segregated South. … Think about what’s going on the child’s head.

And let’s think about his last name. Even for me, how would I be if my name were Regina Miyazaki? How would I be perceived on paper? How would I be perceived when I introduced myself? I wouldn’t be able to say, “Oh, I completely identify as black.” I would have known him, or at least I would have known things from my father. I assume my father would have been proud of his dad?

There’s a whole history of family bonding, family everything, that just was not able to happen because of this ruling to take Japanese in America into these camps.

I was always raised around talking about what’s right, what’s wrong, about racism, about equal opportunities—everything that related to making the world a better place for all people. My mom (Jean Patterson Boone) also was an activist. … She was the first woman to walk on the floor of the state Capitol.

He never talked about it, but I think that’s what drove my dad to be such a crusader of justice. He just wanted to make this world a better place … fighting all the wrongs of the world, especially when it had to do with people being different.

When my dad was dying of pancreatic cancer, in 2014, he told me on his deathbed: Please, you need to find out about this story. You need to let the world know what the American government is capable of doing and what they did to our family.

I want to know my grandfather’s full story. I want to know why he came to the States. I want to know how he felt being in this black community in the rural South, the segregated South. I want to know about the love story he had with my grandmother. I want to know how much he loved my father and my uncle. I want to know what it was like to be ripped away from your family and what pain he must have been feeling, not knowing (was he) ever going to come back to this woman he loved? To these two boys? … I want to know what it was like inside the camps. … I want to know how he felt, beyond these letters I read.

It just breaks my heart, but I get strength from it, too.

This can repeat itself … singling out people who are not “from” the United States … immigrants, and people tagged as “other.”

If we forget these stories, then we forget a whole chunk of American history.

This is not just my history. This is our history.

*This article was originally published on Detroit Free Press on January 14, 2017.

© 2017 Nancy Kaffer