What city did you grow up in?

Betty Shibayama (BS): It was a town, Hood River. It was about 50 miles east of Portland, along the Columbia River. Beautiful country there. It’s like, what they say, like red neck country. [laughs] Well, they wanted to get rid of the Japanese, right. But our neighbors–I only found this out recently from one of my brothers–when the evacuation notice came out, our neighbor who maybe lived a mile away from us, had told my father, ‘Don’t report for the evacuation.’ Because he was a hunter and a fisherman, and he would go in the mountains and he says, I know where I can hide you. And he said they won’t find you and he would provide food and shelter and he said don’t go, don’t go. But my dad said, I can’t expect someone to do that. And our family was so huge. I mean he really appreciated that offer. But he was really a good friend. So there were a lot of people that wanted to get rid of us but then there were good friends.

Did that neighbor offer to keep your house for you?

BS: Well it was leased. But our possessions, I don’t know where my father put them, we must’ve put it in storage. I don’t know where they stored it. Because he went back. While we were in camp, he went out to work. My father said he didn’t decide whether to go back to Oregon because people who went back said there was so much prejudice. And so my two older sisters had moved to Chicago because there were jobs out there and they were hired as housemaids. And my two older sisters said, “Why don’t you just move to Chicago and forget about Oregon and start a new life?” And that’s why my dad went to check Hood River before. And when he went into town, he went into a restaurant during lunch. And they wouldn’t serve him. And he tried a few places that said “No Japs.”

So then my best friend’s aunt had an electric store in town and she was friends with my dad. And so my dad went in there and he was visiting with her. And she says, “By the way did you have lunch?” And he says, “No, I couldn’t be served,” And she told him to stay there and she went and got food for him.

And she was hakujin?

BS: Yes, she was. And there were some Japanese Americans who were in the 442, and from Hood River. There was one that went to visit his family and he had his uniform on and he stopped to eat at a restaurant. And anything he ordered, they said they don’t have. So he saw some guys drinking beer–he didn’t drink beer but he ordered a beer–and they said they don’t have any. And he said, “How come you served them beer?” The guy said, “Didn’t you see the sign when you came in? We don’t serve Japs.” And he had his uniform on. That’s how bad it was. And a friend of my sister’s, one of her best friends, wouldn’t even talk to her. I said, what a friend, that’s not a friend.

Well it shows also that it’s probably the parents that instill that in the kids. How did your family end up in Tule Lake?

BS: From Oregon, we thought my father would see in the paper and he said, “Oh the people of Portland are being sent to the fairgrounds, stockyards or whatever. Well they sent us all the way down to Fresno, I think for three months. The camp wasn’t even ready. My brother said we were living in tents and it was hot. We had to stand in these lines for the mess hall, in the heat, and a lot of the Issei women standing in line would faint. I’d stand in line with my mother and I’d think, please don’t faint.

We were there for about three months and then they sent us to Tule Lake, and then they had the so-called loyalty test. And I guess they considered my father loyal. So after Tule Lake became a segregated camp, then we were sent to Minidoka. They were supposed to have sent us to Heart Mountain [Wyoming] but then my dad said he wanted to go to back to Oregon and since Idaho was closer to Oregon than Wyoming, we went to Minidoka.

What do you remember about the food?

Art Shibayama (AS): We had it better than them because we didn’t go to a mess hall, we cooked at home. According to the size of the family, they gave us kerosene stove and an ice box. And we would go to the market. And we used to get a quart of milk for each kid, a day.

Wow, that’s a lot, right?

AS: Oh yeah. And in those days, the cream used to float, rise to the top. So when it was a birthday my mother used to ask for extra milk because it was delivered by the internees. And extra ice. So my mother used to make ice cream from that cream.

BS: His mother was a good cook and I’m sure she made substitutions. Then there [Crystal City] you eat together as a family. But in camp my brother said he’d roam and go to different mess halls and find out which one had the best cook and they’d go eat there.

Do you remember anything specific you would have to eat a lot?

BS: Well, my father and the men would say they’re feeding us horse meat, there was something that was dark, and it wasn’t beef, you know it wasn’t beef. And the men would say, “They’re feeding us horse meat.” I’m trying to think what else. You know the kids get hungry, what can you get? Well there was always extra bread. And we’d take the bread but there was no peanut butter and jelly, so we’d get the Mayonnaise and then we’d have lettuce and that was it, we’d have a lettuce sandwich. I remember we’d be eating that as a snack [laughs].

AS: But compared to them, a couple of my buddies used to work at the market. They used to bring home peanut butter, loaf of bread, jelly. And then another thing is, we used to have a grapefruit and orange orchard inside the camp. So on the way to school, we’d walk around the outside and we’d see where the ripe ones are and at night we used to sneak in there and pick them. We could get them at the market but somehow this one tastes better. To make it worse, my father was a policeman [laughs].

[To Art] When you went to Seabrook, did you experience prejudice like that?

AS: No, plus there wasn’t much prejudice on the East Coast.

BS: Because in California there were a lot of Japanese. But Fusa, his sister, told me that when they went to Seabrook it was mostly Japanese anyway, but it was mostly Japanese Americans. She felt kind of alienated, that they treated–because they hardly spoke English, right?

AS: We didn’t speak English.

BS: Right, they spoke Spanish, and then they spoke perfect Japanese. Not like the Japanese we spoke. That’s why she said they were treated differently, because they were dark and she said she was treated differently.

AS: We were the last ones that went to Seabrook, it was like camp. All Peruvians were put together, and one Peruvian guy had a bad reputation. But I made the Seabrook farm [baseball] team and after that, everything cooled off. I was the only Peruvian on the team.

BS: They were all Japanese American.

AS: We had a couple of kibeis who were in Crystal City. But most were JA’s.

Do you still speak Japanese?

AS: Not as good. We went to Japan for vacation for five weeks. And only one of my relatives spoke English. So I was forced to speak Japanese everyday so it came easier. But now I only use it once a week, twice a week, so you forget it.

How about Spanish?

AS: Same thing, Spanish. When I was in the service I went to Spain on furlough. I went with an Italian guy. And they’re all looking at him, the Italian guy, and I started talking and they’re looking at me [laughs] And this is in the 50’s!

It was fun to watch your documentary and see all of those Japanese Peruvians speaking Spanish. It just shows how everybody ended up everywhere. So how did you finally get your citizenship?

AS: When I was in the service, I was a clerical typist. We used to do all the paperwork for the European command. So one day, our section leader was like a lawyer and knows army regulation inside and out. He comes to me and says, “Hey, Art! How come you’re not a citizen?” So I told him what happened. And he says, “Oh, I’ll get you one!” So the paper went to Washington, came back, and said I was denied because I didn’t have a legal entry. He got kind of messed up, too. [laughs] So he asked me what happened and I told him my story, and he says, that’s kind of funny.

BS: See because after he was discharged, he reported to the immigration in Chicago and he said they had to study his case because they never had a case like his before. So it took about a year for them to get back to him and then when they called him, they told him they had to go to Canada with a letter. To Windsor county, they had to cross over with this letter and then you come back and that’s where he got his permanent residency. And that was 1956, so that’s why he was denied redress because you had to have been a citizen or permanent citizen at the time of internment. So that’s why he was denied. Isn’t that ridiculous?

You couldn’t make it up if you tried because of how convoluted it is. And in the film, the redress was kind of an insulting amount right, which you denied?

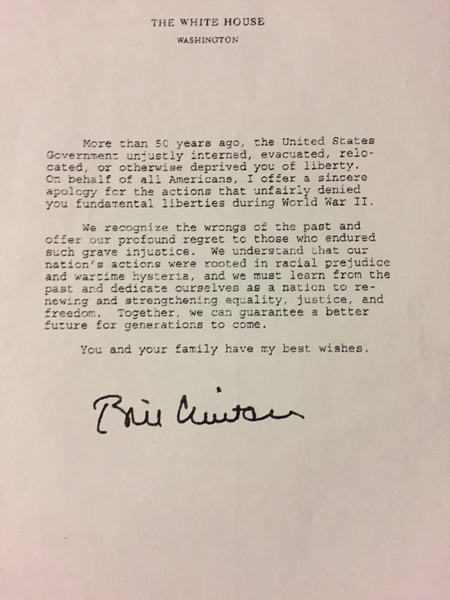

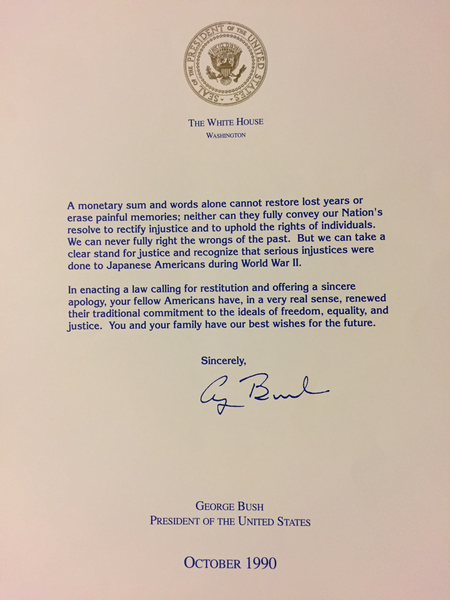

AS: Not even that but the letter of apology. Betty’s has a letterhead.

BS: Have you seen the one they got?

No, I haven’t.

BS: There’s no letterhead or anything, and it doesn’t even mention Japanese or Peruvians, I’ll show you.

AS: It was like they could give it to anybody.

BS: See, there’s no letterhead. Yeah, it doesn’t even say. “You and your family.” At least Bush said “sincerely.”

This could’ve been for anybody.

BS: It’s an insult. So his two brothers sided with him but he had two sisters who were living accepted it [$5,000].

AS: But my mother and one of my sisters received the $20,000.

How did that happen?

AS: I don’t know they made a boo-boo somewhere [laughs].

BS: No it’s because, you know the Japanese war brides? They used to have naturalization classes in Chicago, and she used to go. And it’s through that process they got their citizenship without going to Canada. And because of that they were able to receive redress. But because they went across the border, came back, you do what you’re told to do [laughs].

AS: I asked a lawyer why my sister got it. And they said each case is handled differently.

Art, you seemed to get the worst end of the deal.

BS: Yep. And they’re just waiting for people to die off so they don’t ask.

And how many Peruvians were there?

AS: 1,800 total.

You’d think one of the governments could afford to pay up. Do you know how many Peruvians did accept the $5,000?

AS: I think only 17 refused and the rest accepted, especially the people in Japan. Because Japanese don’t sue the government. They were the first ones to accept it. At that time, Patsy Mink was helping us the most. And she really got upset when we accepted $5,000. She was going all the way but then she died, so.

And nothing came from Peru?

AS: Well the Peruvian government donated land for the Japanese community. So the Japanese community built an Olympic sized pool and field and all of this stuff.

So what is the status of the group fighting for redress?

AS: We’re supposed to have a meeting next year [2017]. But now that we have a new president, I don’t know, that might go down the drain, too. Because we were supposed to have a senate hearing in February of 2002 but 9/11 happened, so the thing got moved and backed up. But Grace Shimizu is someone you should talk to, she’s the one who’s still working on this.

Do you personally feel like there’s been any closure on what happened, or are there still so many loose ends?

AS: Well [Xavier] Becerra was helping us from the beginning. Patsy Mink and Becerra.

BS: And a Republican, Tom Campbell, called us and said, “Is there anything I can do for you?” Because he knew about us from reading it in the paper. We didn’t even approach Tom Campbell. He called us. But every time an event was going to happen that would be beneficial for the Peruvians something came up.

So tell me how you two met.

BS: In Chicago. So when we got married, we got married in ’55. Actually he was still considered an illegal alien. A year later we went to Canada and he crossed over.

And where did you meet?

BS: It was a Friday night get together, it was like a social club. And so that’s where I met him.

So you were in high school?

BS: Yes I was.

AS: I never saw high school.

That’s right, you said you just went to work immediately?

AS: Yeah. When we got out of camp, there were six of siblings and my mother was pregnant when we got out of camp. And my father, by being illegal, he had to pay 30% income tax out of his salary. And being illegal, he couldn’t get government aid. My sister and I had to work.

And why the move to Chicago?

AS: Because he had friends. By then, we were in Seabrook for two and a half years, and by that point, he figured we’re never going back to Peru.

Did you feel that your father was ever homesick for Peru? Did he ever talk about it?

AS: He would never talk about it. But he wanted to start something.

BS: Yeah because he was a successful businessman and he just lost everything and had to start all over. And he was a very proud man and–yeah, it was sad.

It is very sad. What did he do in Chicago?

BS: Eventually he owned an apartment building but then he was working, too. And at American Carbon and he worked at a punch press or something and he was working nights, and falling asleep. [To Art] And he lost his thumb, right?

AS: [Nods]

BS: Yeah, you know when you’re sleepy. I don’t know how the thing works but he didn’t move his hand fast enough and lost his thumb. It’s sad because he was a very successful businessman.

Do you yourself have a feeling of loss for Peru?

AS: No. They had a reunion back in Peru and my sisters and them went. But I don’t want to remember the old days, so I didn’t go.

Because it would’ve been too hard or too sad?

AS: Too sad, I think.

Do you feel that way, Betty, about being home in Hood River?

BS: Well, if it didn’t happen, if we weren’t evacuated, I wouldn’t have ever met Art. From Peru, to a little farm girl in Oregon, how would we meet, you know? [laughs] So I have no regrets.

What do you think is the lesson that everyone needs to remember?

AS: Like now, feels like same thing’s happening. Especially with our new president. Like, we never learned.

BS: Just because we look different doesn’t mean we’re the enemy, right? [laughs] Got to get over the prejudices. You’d think we’d learn from the past but we don’t. We seem to be committing it again.

*This article was originally published on Tessaku on January 10, 2017.

© 2017 Emiko Tsuchida