In my case, they denied my citizenship because I didn’t have legal entry. Now, the government brought us here forcibly, on a U.S. army transport, put us in a justice department camp that was administered by the immigration. So, where’s the place where it says I’m illegal?

-- Art Shibayama

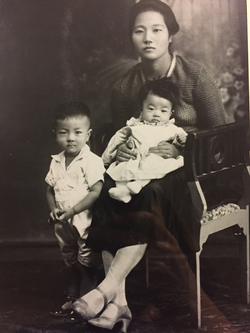

Art Shibayama’s childhood was idyllic. His summers were spent swimming off the coast of Callao, where his loving grandparents essentially raised him. Back in Lima, his father ran a successful business importing textiles and selling dress shirts for wholesale. His family had domestic workers to help with the house; chauffeurs to pick him and his siblings up from school; a beautiful house and a car. By any standards, Art’s childhood was nearly perfect.

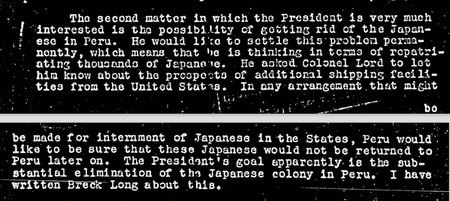

And then, America went to war with Japan. While the policies of the internment were taking hold along the West Coast of the U.S., Peru was hashing out its own sordid deal with the United States: Extradite the Japanese Peruvians as hostage bait for Americans in Japan. In exchange, the U.S. would continue its financial and military support of the country, keeping its interests in the Panama Canal safe. And similar to the palpable anti-Japanese sentiment along the West Coast, President Manuel Prado rode the wave of Peru’s own prejudice, ridding the country of Japanese businesses and financial competition. In sum, both governments found great advantages to more or less kidnapping people from their homes.

Art, who was the oldest of six, would eventually be a key person in leading the fight for fair reparations for the Japanese Peruvians. Refusing to take the rather pathetic monetary sum of $5,000 from the U.S. government as an apology, Art has continued to speak out about this history and has continued to demand a fair acknowledgement from both governments that atrociously violated their civil rights.

Now at 85 years old, I spoke with Art Shibayama and his wife, Betty in their home in San Jose. Betty’s own story about internment was also a fascinating piece that added to the mosaic of their relationship and marriage, where overlapping family experiences (or, tragedies) brought them into contact. Art is honored as one of the candle lighters, representing the Justice Department camps, at the yearly Day of Remembrance in San Francisco.

You can watch his documentary, Hidden Internment, here.

* * * * *

I’ve been looking forward to speaking with you now, as it’s been a while since those years of fighting for redress and justice for the Japanese Peruvians. What, if anything, has changed for you? I wanted to see how your perspective changed.

Art Shibayama (AS): The reason I went into the service is that I was fighting deportation and some people went to Japan and my dad didn’t want to go to Japan, there wasn’t enough food. So I figured, if I go into the army, there’s less chance for deporting me.

Betty Shibayama (BS): Because he was considered an enemy alien and he was fighting deportation and he couldn’t return to Peru. Citizens could return but the parents couldn’t. And he was a minor so, he wouldn’t go back alone.

AS: I was in bad shape. [laughs]

Well, that’s what I was curious about. How could you even be drafted if you weren’t a citizen? It doesn’t make sense but also shows the injustice of the government.

AS: And usually if you get drafted, they give you citizenship if anything, But in my case, they denied my citizenship because I didn’t have legal entry. Now, the government brought us here forcibly, on the U.S. army transport, put us in a justice department camp that was administered by the immigration. So, where’s the place where it says I’m illegal?

It was like you were without a nation.

BS: Yeah, at one point, he had no country. He was a man without a country.

If we were going to start with your childhood in Peru, what are some of the highlights of being young and growing up there?

AS: Going to school, playing sports.

BS: They were well-off. Because they had maids, and chauffeurs that drove them to school.

AS: We used to go to Japanese private school and they were teaching and Spanish every other period. And the younger kids were small so my father told my chauffeur to take us to school and pick us up.

That makes this even more tragic.

BS: Yeah. Because everything was taken away so when he came to the U.S.

Your father wanted to go back to Peru but what kept him from going?

AS: The Peruvian government wouldn’t take us. The only people that were allowed to go back were people that had Peruvian wives or Nisei wives, because Niseis were Peruvian. But if both parents were Isseis, they wouldn’t take us. Because actually, Peru wanted to get rid of all the Japanese. That’s why they were taking 2,600 from other countries, from 13 different countries. But out of the 2,400, 80% were from Peru. Because the President Prado wanted to get rid of all of the Japanese.

BS: Because they were successful.

So they didn’t have Peruvian citizenship. What about your grandparents?

AS: It didn’t even matter because my grandfather had Peruvian citizenship but they still took him. And he was sent to Japan before the end of the war. So actually, if he was still in the U.S. after the war, he would’ve been able to go back because he was a Peruvian citizen but he was already in Japan. He wasn’t voluntarily, he was forcibly sent.

And your grandparents just lived there for the rest of their lives?

BS: Yeah. He never saw them again after they were taken. Because he was the oldest in the family, and he was the first grandchild. So his grandparents had a shop in the port of Callao. [To Art] you actually lived with them, didn’t you?

AS: I lived with my grandparents before I started school. My parents were in Lima, and my grandparents were in Callao. I used to spend my summer vacations there because Lima doesn’t have any water. Callao is the port for Lima actually. So I used to stay there and went swimming everyday in the ocean.

Did your grandfather go swimming too?

AS: Yeah, they went before they opened the store and I used to go with them, then come home and I eat breakfast, lunch. Then I used to go back again to the beach to meet my friends.

You were living the life. And so were your grandparents. Where in Japan were they from?

AS: Fukuoka. He had a brother in Japan but they never came.

BS: And his father’s parents were gone.

AS: That’s the reason he went to Peru because he [his father] died when he was 15. And he went because he had an uncle in Peru.

That’s hard to imagine that you never saw your grandparents again.

AS: I was almost closer to them than my own parents for a while. When I started kindergarten or first grade, we started playing baseball against the other classes. Naturally I needed a baseball glove so instead of asking my father I called my grandfather and told him. He came all the way from Callao to Lima and got me a glove and a bat.

He was like your parent, they raised you. So when they left Peru, you were twelve by that time?

AS: Yeah.

What do you remember about them leaving?

AS: I don’t even know when they were taken. I really don’t remember anything. I was living in Lima and they were taken from Callao.

It’s more heartbreaking to hear about all of these ways you were plucked from where you lived and how your family was scattered. And you’ve mentioned in many interviews that your father went into hiding right after the war started. What do you remember about that?

AS: When people found out that the U.S. army transport came into the port of Callao, word got around. So a lot of head of the family went into hiding.

Where did they go?

AS: I don’t know. But my father went near the mountains, near the Andes because he had a friend up there.

BS: So he figured they wouldn’t go looking for him.

AS: Yeah, by then, they took my mother and put her in jail. So then my younger sister, Fusa-san’s godfather was a Peruvian, so he went and told my father what was happening. So he gave himself up.

BS: Yeah because they arrested the mother, and the sister right below [Art], was 11 years old, didn’t want the mother to go to jail alone. So they were put in jail. And she told me that she says, all she did all night long, because she was thrown in with prostitutes, and thieves, all they did was hug each other and cry all night.

Were you alone during that time, were you by yourself?

AS: I was with my mother and my siblings. And then my godparents lived next door.

Do you know how long they were in jail?

AS: I think overnight or a couple of nights.

BS: I think Fusa told me that your father said that he would come out of hiding and if they could go as a family, they would. They probably figured the more hostages the better.

Did your parents explain to you and your siblings about what was happening? Did you ever understand that you were basically being kidnapped?

No. You know how the old Japanese parents are. They don’t communicate with their kids. It was the same with my dad.

Were you scared, or did you feel like something bad was happening?

No, because we were all together.

Some other people have said the same thing, they didn’t remember it was being scary. It was only after the fact that they understood what their parents went through.

BS: Well, I lived on a farm in Oregon. And I was the youngest of eight kids. So late at night after Pearl Harbor, my parents thought all the kids were sleeping. I couldn’t go to sleep but I heard my parents talking to my oldest sister and oldest brother. They said that because they’re not citizens, they might be sent back to Japan. So they told the oldest two that they would be responsible for the rest of the family. And when i heard that, because I was only eight, I Just couldn’t imagine life without my parents. So I just dreaded what was going to happen. And when we found out that we were going as a family I was so happy, I didn’t care where we were going, as long as we were going as a family. Thinking you were going to be separated from your parents, but you get to go as a unit, I’ll go anywhere they go.

You thought it was going to be much worse, that you’d be separated.

BS: People ask me, ‘Weren’t you scared when you got on the train?’ and I say no, I was happy. I didn’t care where we were going, as long as we were going with my parents.

*This article was originally published on Tessaku on January 10, 2017.

© 2017 Emiko Tsuchida