“I remember my father saying how angry he was and that he would never again vote. And he never did."

—Grace Izuhara

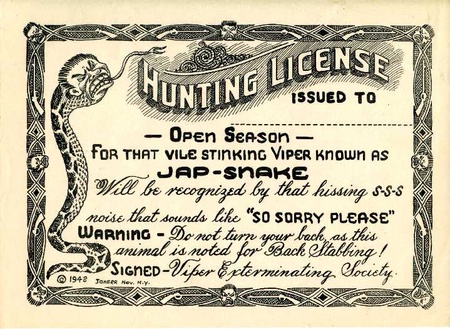

Grace Izuhara’s family was one of the “lucky” few that escaped imprisonment in the camps during WWII, heading east to Utah to work on sugar beet farms, a vital wartime staple. “Lucky,” because despite their independence, anti-Japanese fervor still ran high in their new town of Clearfield, resulting in a few traumatic events that Grace can still picture. She remembers seeing “Hunting Licenses for Japs” signs hung in store windows. When her brother needed urgent medical attention, they had trouble finding a hospital that would see him. And while they lived free, the price was paid in bitterness: Grace’s father refused to vote for the rest of his life.

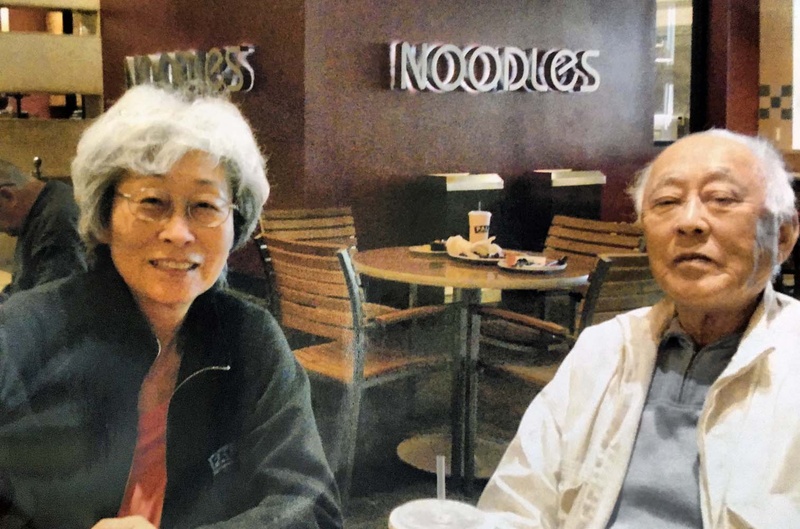

Our paths intersected at the Manzanar pilgrimage, where her husband Tom was incarcerated as a young boy. They were just shy of their 58th wedding anniversary when he passed last July. She attended Manzanar alone this year, revealing that he never wanted to go back and see the place where he and his family were once imprisoned. “My husband could never say why he didn’t want to visit Manzanar but when I felt the emotion at the cemetery and monument, I knew why. He was feeling the pain and the sorrow not for himself but for his mom and dad.”

* * * * *

How old was Tom when he was there?

I think he must have been about 10 years old. For children, it can be fun because they have lots of playmates and I know that for the women life became easier for them. Because they worked so hard—they were expected to work in the fields and then also do house things. When my husband was younger, he remembered the fun parts but as he got older he became bitter about it. I remember my father saying how angry he was and that he would never again vote. And he never did.

Wow. So after the war, he never went to vote at all?

No, after the internment he never voted again.

Where were you living before the war broke out and what were your parents doing?

My mom and dad farmed. And my memory is that we lived in North Hollywood. I was born in 1936. I must’ve been about five or six. After Pearl Harbor there were blackouts and there were shades and thick curtains over the windows. Then my father decided he would take us to Utah where it was far enough inland that we were not considered a threat. I still remember when we left the house, and it still affects me.

What do you remember about leaving?

I was looking out the back window of the car and our dog was standing in the driveway watching us go.

Did you have a neighbor that took the dog?

Yes, and then my mom got letters that our dog would go back to look for us.

Heartbreaking.

Yes, still. I remember the drive to Utah at nighttime being so dark and of course we would have to stop by the road to pee. And of course that’s when another car would come by [laughs]. In Utah there were already some Japanese families there. The only name I can remember now is Endo but beyond that I don’t remember.

My father raised sugar beets and it was considered a war staple so he was exempted from the draft. I remember during harvest that German prisoners of war would be brought to the farm and I had never before seen such tall, white people. They were so pale. And I remember my father telling my mother to make coffee for them and they were very grateful for the kindness.

So they were brought in to farm for sugar beets?

Yes. The guards had guns, they were brought in on a truck. And I remember their lunches: Thick slices of bread with one thin slice of bologna.

And you saw all of this because people were walking around where you lived?

I think our house was on the farmland. I remember there was an outhouse that was dug. Oh that was horrible, I hated the outhouse. We could see the Salt Lake from the kitchen window and there was an irrigation channel that ran by the house. And I hated the mosquitos.

Did you have siblings?

I had a younger brother and then we had a baby sister. Susan was born in Utah.

We were not welcomed in Utah. When the hunting season started, there were signs in stores for people to get a hunting license and there was a sign that said, “Hunting Licenses for Japs, Too.” And one of the workers on my dad’s farm who was also a good friend, a bullet hit his boot while he was in the field.

Do you remember your parents speaking about feeling afraid?

No. I don’t remember them saying anything. They may have but I never heard it.

Did you attend school?

Yes, I still remember one boy in particular who was a bully. When I was younger I would’ve liked to have met him again [laughs]. I still remember his face, his name was Michael.

He picked on the Japanese kids?

On me.

Were you the only Japanese student?

I think I was but I’m not sure. I don’t remember any other Japanese boy or girl, but there must have been. Perhaps not in my class. I just remember this ratty Michael. I don’t remember having many friends. I did tell a lie though, so I could be accepted. I said that I had an uncle who was killed serving America but that was a lie.

When you said that, did you find that kids changed their attitude towards you?

Not a whole lot, I think it gave them pause. But if they went home and talked to their parents, I think they would’ve known that I was lying.

After the war was over, my mom and us kids were the last to leave the house but my mother had forgotten something so we went back. I guess we had only been gone a few minutes and when we went back, our ratty neighbor was already pulling the fence down.

Your family took this huge chance leaving California to settle in that town without knowing the attitude of local people.

My mom and dad never talked about it. My maternal grandparents went to Denver, Colorado. They went further inland. And we were able to go visit them at least once. My brother was on the floor of the car, and to raise himself up he grabbed the door handle of the car, it swung open, and he fell out and as he fell the door bounced back and cut him on the side of his head. And it was so hard to find a hospital or ER that would take him. There were doctors who wouldn’t take him. And finally my father, and uncle who was driving, were able to find a doctor.

Listen to our conversation here:

Thank you to Alyson Iwamoto for coordinating this interview.

*This article was originally published on Tessaku on May 21, 2017.

© 2017 Emiko Tsuchida